by Bethany Blake

Published April 11, 2025

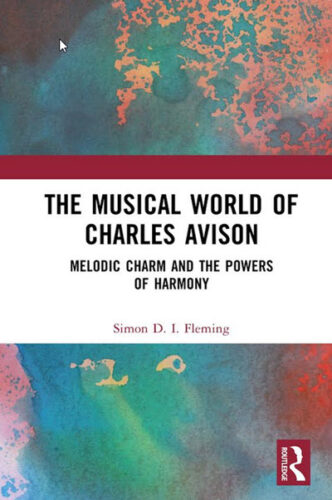

The Musical World of Charles Avison: Melodic Charm and the Powers of Harmony by Simon D.I. Fleming. Routledge Press, 2024. 307 pages.

The main premise of Simon D.I. Fleming’s The Musical World of Charles Avison: Melodic Charm and the Powers of Harmony is that Charles Avison (1709-1770), most famous for his 1752 treatise An Essay on Musical Expression, should be viewed not just as a music theorist, but also as a composer. Fleming contends that Avison’s musical compositions influenced European composers to a greater extent than previously realized, and that his compositions exemplify his theoretical arguments.

The author begins by considering why Avison’s impact has been overlooked. After citing the well-worn perspective that the 18th century was a dead age for British music following the death of Handel — “Das Lande ohne Musik,” per Oscar Schmitz’s notorious phrase — Fleming mentions that additional information on Avison’s compositions has emerged over the last 25 years. Referring to Avison as “our composer” (emphasis mine), he exhorts the reader to acknowledge Avison’s legacy not only as a philosopher of music aesthetics, but also as a noteworthy composer. (Together with this book, Fleming has supported the current promulgation of Avison’s music by helping to produce the Avison Ensemble’s recordings of his compositions.)

Fleming’s argument that more attention should be paid to Avison’s compositions is useful for broadening our understanding of his role in British musical society during the Georgian era. Chapters are organized chronologically by compositional endeavors, followed by two summary chapters concerning the reception of his music during his lifetime and his perceived historical impact since then. While surviving sources offer little information about how often Avison’s music was performed in contemporary concerts, Fleming provides data demonstrating that, over the course of Avison’s lifetime, the number of consumers subscribing to purchase his published music increased.

In comparison to previous studies, Fleming goes more in depth with data regarding subscriber demographics by locale. His research reveals Avison’s previously overlooked popularity in Scotland and its relevance to northeast English and Scottish musical societies. Fleming also clarifies that Avison’s choral arrangement of “Sound the Loud Timbrel” was based on a tune by Irish poet/composer Thomas Moore, rather than an original melody by Avison. Perhaps ironically, this chorus was the primary reason for continued awareness of Avison during the first half of the 19th century, despite its conflicting origins.

Fleming’s research offers the fullest compilation of specific data from performances, subscriptions, publications, and reception of individual pieces, which will be of use to scholars studying musical life in the Georgian era. Moreover, Fleming’s text moves past simply filling in the holes in our biographical understanding of Avison to ask the broader question of how he integrated and applied his more famous music aesthetic ideals into his own compositions.

In his Essay, Avison claims that one’s personal emotional response to music is ultimately more meaningful than the degree to which the composer adhered to historically cemented tenets of music theory. Few 18th-century British composers wrote about their aesthetic values to the extent that Avison did. Fleming posits that it is therefore all the more productive to examine whether his aesthetics were exclusively theoretical or in fact borne out in Avison’s personal compositional practice. Since there is already well-established scholarship analyzing Avison’s treatise, Fleming attempts to connect Avison’s aesthetic principles to their perceived manifestation through his instrumental and vocal compositions.

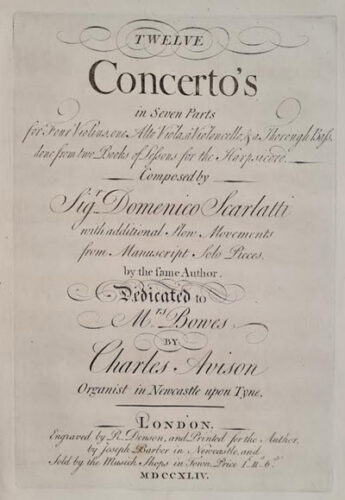

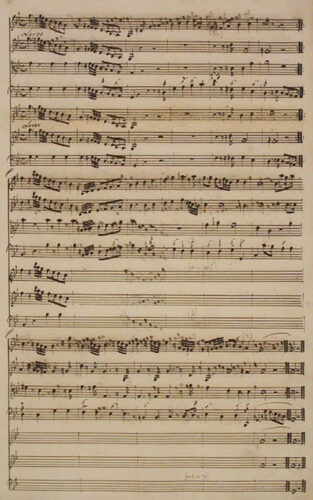

Avison’s concertos, his most popular compositions during his lifetime, are Fleming’s main focus. Quotations from the full extent of primary sources, including Avison’s prefaces, letters, dedications, and so forth, supplement current scholarship focused on the Essay. In Chapter 7, Fleming identifies specific overlaps in writing between Avison’s treatise and his preface to the Op. 3 concerti. Avison asserts in the Preface that the concept of the Essay was born from writing lengthy instructions to performers in prefaces to his publications. Fleming then addresses criticisms made by contemporary composer William Hayes, attempting to provide more context for why Avison composed as he did.

For example, Hayes identifies the second movement of Avison’s Concerto,Op. 3, No. 1, as a poorly written fugue, stating that the fugal subject is “trite, the Air [melody] mean and low, not capable of being turned to any great Advantage… [and…] where it cannot be pronounced absolutely wrong, it is so very bald and puerile, that it deserves to be erased or blotted out.” However, Fleming contextualizes Avison’s defensive retort within his aesthetic principles, citing that Avison understood the second movement to be imitative but not strictly fugal, believing that music should not follow rigid structural and contrapuntal rules. Instead, he believed music should follow “nature” by allowing for flexibility within imitative textures.

Fleming asks whether Avison’s appeal to this amorphous, intuitive concept of “nature” is simply a coverup for lack of contrapuntal skill. He points out that Hayes was influenced by the stricter, Germanic approach to fugal writing, while Avison seems to have taken the freer Italian fugal style as his model. Fleming also addresses Avison’s occasionally questionable orchestral scoring and key choices present in his later concertos of the 1760s (when compared to his overall musical output). He surmises that the perceived deterioration in quality may simply be the result of ill health and subsequently less revision time.

Through musical examples and analyses, Fleming argues that Avison abides by his own underlying belief that the rules of harmony were meant to be learned and subsequently broken for the sake of being expressive. This familiar argument is easily traced back to the early 17th-century Monteverdi-Artusi debate, in which Monteverdi famously claimed that “the words are the mistress of the harmony,” and simultaneously reflects Avison’s stylistic milieu of the mid-1700s, where the complexity of the German High Baroque intersected with the simplicity of the nascent Italian school of Pergolesi and Sammartini. Fleming suggests that Hayes’ criticisms of Avison’s ability were taken at face value despite containing some misinterpretations.

As an advocate of Avison’s work, Fleming ultimately desires The Musical World of Charles Avison to demonstrate Avison’s broader impact on his time. Fleming asserts that when using a more nuanced, “sliding scale” that assesses influence, Avison should be no lower than the “third quartile.” Regardless of how convincing readers find his argument of influence, this book will appeal to British music enthusiasts wishing to increase their understanding of both the aesthetics and lived musical worlds of 18th-century English composers, as well as scholars interested in untangling the relationship between printed text and musical score among theorist-composers.

Bethany Blake is a music historian and keyboardist at the University of Vermont. Her research focuses on vocal music societies in 18th-century England and the ways in which their music reflects an intent to establish an English musical identity within the broader European canon.