by Ashley Mulcahy

Published July 20, 2025

Change ringing is a church activity, yet its secularization is almost as old as the activity itself

‘We don’t ring tunes, we ring patterns’

Described as a “mathematical and musical team sport” by the ringers at Smith College’s Mendenhall Tower, and as “math for musicians” and “exercise for engineers” by ringers at Trinity Wall Street, it is challenging to categorize the historical practice of change ringing.

The North American Guild of Change Ringers provides a good starting place, defining this mathy-musical-sport as “groups of people cooperat[ing] to change the order in which they ring their bells according to a precise pattern,” where each person in the group (aka band) rings just one bell.

Though there is evidence of change ringing in North America as early as 1744, it is unlikely that you’ve heard change ringing live unless you happen to live near one of the just fifty towers across the U.S. and Canada where it is regularly practiced. While fifty towers may not seem like many, the popularity of change ringing in North America has actually grown since the early 1960’s, when the number of active towers in North America was just seven. Though today’s ringers in some 7,000 towers world-wide enjoy change ringing as an obscure historical hobby, the technological advancements that first enabled change ringing developed to address a purely practical need: volume.

In the 2013 BBC documentary Still Ringing After All These Years – A Short History of Bells, presenter Richard Taylor explains that during the 11th century, bells in England began to play a role in daily civic life. “Bells announced the big moments,” says Taylor, “like when the master’s oven was hot enough to bake the village bread” or when it was time for the evening curfew. Around 1600, technology had advanced such that bronze bells weighing anywhere from several hundred pounds to several tons could be mounted on wooden wheels and rotated 360 degrees. Ringers at Boston’s Church of the Advent elaborate: “The bells could then be rung by means of a rope running in a channel around the wheel’s rim down into the room below where it was pulled by ringer.” As a result, bells could ring out louder, and villagers in distant fields could more easily receive important signals.

In addition to increased volume, this new system allowed bellringers to exercise greater control over the timing of a bell’s peal. “Bells ring naturally from lightest to heaviest” notes Taylor. “The wheel let ringers control the bell’s pace and change the order in which they rang.” But no success is without sacrifice, and in optimizing volume and control, the engineers of this system compromised speed. The time that it takes for each bell to fully rotate makes playing melodies impractical. “To get the bells to be really loud, they actually ring from mouth up all the way back around to mouth up,” explains Boston area ringer Danielle Morse in a video about the MIT Guild of Bell Ringers. “Because it takes a while to ring the bells that way, we don’t ring tunes, we ring patterns.” (The MIT Guild rings at Boston’s Old North Church and Church of the Advent.)

Like any art or sport, there are principles that govern change ringing. Many of the principles that ringers follow today were first published in Richar Duckworth’s 1668 treatise, Tintinnalogia, or, the Art of Ringing. Say, for example, that a group of ringers is sounding a pattern on five bells. Duckworth illustrates these five bells with a row of numbers, where 1 is the bell with the highest pitch and 5 is the bell with the lowest pitch: 12345. As the pattern progresses, no bell may sound more than once in a row. So while 12345 is permissible, 11234 is not. Additionally, bells may only change their place from one row to the next by one position. So while 21345 could follow 12345, 23451 could not.

About a decade later, Fabian Stedman (the publisher of Tintinnalogia) described it this way in his treatise Campanalogia: or the Art of Ringing Improved: “. . .if five men were sitting upon five stools in a row; the stools are supposed to be fixed places for the five men, but the men by consent may move or change to each others places at pleasure, yet still sitting in a row as at first: now this Art directs how, and in what order those five men may change-places with each other, whereby they may sit sixscore [120] times in a row, and not twice alike. And likewise a Peal of five Bells. . . may strike sixscore [120] times round and not twice alike.”

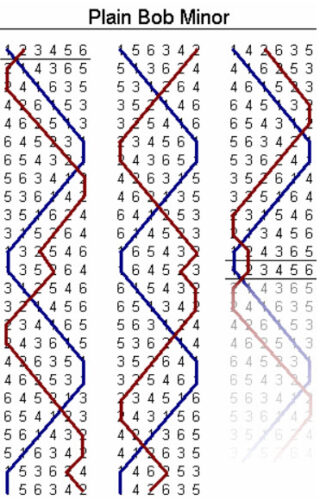

If this all sounds like math, it’s because it is. The patterns of ringing that appear in both treatises are governed by the mathematical principle of permutations. Different patterns of permutations are known to ringers by their titles, and today’s ringers play many of the same patterns that their 17th century forebearers enjoyed, like” Plain Bob minor,” shown here in the chart.

On an unusually hot and humid June evening, ten or so members of the MIT Guild of Bell Ringers gathered for their weekly Wednesday session at Boston’s Church of the Advent. Undeterred by the weather, they climbed the windy steps to the church’s unairconditioned, carpeted tower, no larger than 12’ x 12’. At some point, the leader of that evening’s session, sometimes called a “conductor,” called the pattern “Plain Bob minor!” The ringers took their positions.

Ringer John Bihn kindly handed me a copy of The Ringing World Diary, an almost pocket-size publication that many ringers today use as a reference. He opened the page with the pattern for “Plain Bob minor.” Then he interrupted himself. “Wait! Let me show you so you can zoom in.” He took his phone from his pocket and pulled up iAgrams, one of several apps for change ringers.

“Go, Plain Bob minor” yelled the conductor, and the pattern began. As in the 17th century, today’s ringers play together by memorizing patterns. A less experienced ringer will stick with just one bell throughout the whole practice session, while more experienced players like Bihn might switch from one bell to another and therefore change their place in the pattern as the group works through each permutation. In addition to silently counting through the permutation, ringers listen for each peal and carefully watch each other to properly time their own bell. “When you ring with the same group of people for a long time, you pick up on each other’s body language,” added veteran ringer Greg Russell.

After about an hour or so, the group took a break from ringing patterns for some instructional time. More experienced ringers paired with less experienced ringers. Bihn guided me through the backstroke, which, just as in 1668, is the first motion a ringer must learn before, as Duckworth writes in Tintinnalogia, “he is entred into a Company.” The backstroke controls the amount of tension in the rope. Bihn explained that a ringer might spend their first few sessions just getting comfortable with the backstroke before they actually ring a bell. It can take a few months of practice before a novice ringer develops enough skill to ring a pattern, depending on how much “rope time” they are able to get in.

While almost all bell towers are fixtures of church buildings, a ringer may not necessarily affiliate with the church at which they ring. In fact, the secularization of change ringing is almost as old as the activity itself. “Although the bells still ring for church services, from the start, change ringing was considered a sport,” reports the BBC. The St. Martin’s Guild, which operates in and around Birmingham, England adds a bit of detail: “During the reign of James II (1633-1688) bell ringing became extremely fashionable amongst the aristocracy, as it provided physical exercise and intellectual stimulation. In the rural churches, however, bands of ordinary ringers strived to outdo one another. On days of competition the ringing was often preceded by a large meal at the local pub and followed by the presentation of a ‘good hat’ or a pair of gloves to each ringer in the band that had performed the best.”

Many ringers today particularly enjoy the things that change ringing and team sports have always had in common. Geoff Williams, for example, who rings at Christ Church in Calgary, Alberta, calls “the rhythmic coordinated physical activity of working the rope in a band” his favorite part of change ringing. The physical nature of this brain-workout is also key for Julie Keller, who rings at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Little Rock, Arkansas: “I love the fact that I engage both my body and my mind when change ringing,” she says. For John Paul Brabant, who rings at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Honolulu, Hawaii, it’s all about the “game” aspect of realizing patterns, which he finds “fascinating.”

And like their 17th century forebears, ringers today find deep satisfaction in perhaps the most wholesome aspect of change ringing, which Duckworth calls the reader’s attention to in the final section of his introduction to Tintinnalogia: it can only be practiced in community.

When Bells Ring round, and in their Order be,

They do denote how Neighbours should agree;

But if they Clam, the harsh sound spoils the sport,

And ’tis like Women keeping Dover Court

For when all talk, there’s none can lend an ear

The others story, and her own to hear;

But pull and hall, straining for to sputter

What they can hardly afford time to utter.

Like as a valiant Captain in the Field,

By his Conduct, doth make the Foe to yield;

Ev’n so, the leading Bell keeping true time,

The rest do follow, none commits a Crime:

But if one Souldier runs, perhaps a Troop

Seeing him gone, their hearts begin to droop;

Ev’n so the fault of one Bell spoils a Ring,

(And now my Pegasus has taken Wing.)

Ashley Mulcahy is a mezzo-soprano active as a soloist and ensemble singer. She also co-directs Lyracle, a voice and viol ensemble.