by Ashley Mulcahy

Published August 9, 2025

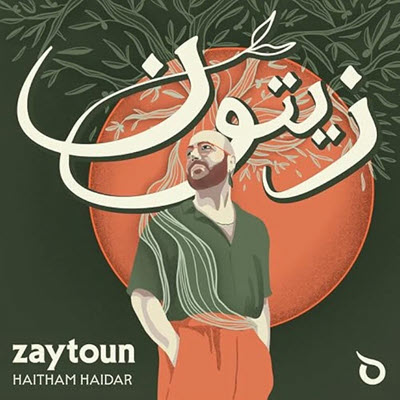

Lebanese-Palestinian Canadian tenor Haitham Haidar’s debut album, Zaytoun, finds ‘connections between what we generally view as separate worlds’

‘Though I trained my voice in one genre, my heart felt like it belonged to another‘

Haitham Haidar has a lot to say. The tenor is bold and effusive, and if he feels strongly about something, you’ll hear about it. But he’s also a good listener, attuned to emotions. His debut album, Zaytoun, is a personal project that seeks to unify the two sonic worlds that feel most like home: music of Arab traditions that were the soundtrack to his childhood and the European Baroque that’s at the center of his burgeoning career, which includes recent performances with Les Délices, Seattle Bach Festival, and Kaleidoscope Vocal Ensemble.

Born to Lebanese and Palestinian parents, Haidar grew up in Beirut. He moved to Canada in 2009 to attend the University of British Columbia and continued his education at McGill and Yale. He’s held Canadian citizenship for several years and has made a home in Montréal. But, like so many who immigrate, he doesn’t always feel at home.

Continued aggression against civilians in Palestine and Lebanon has magnified the complexities around home and belonging for Haidar. And from thousands of miles away, this violence became even more personal when his grandfather’s house in Baalbeck, Lebanon was demolished in a 2024 Israeli airstrike. Thankfully, no one was in the house.

Zaytoun has been an outlet for Haidar to grapple with the existential complexities of his immigrant experience during this time when being at home in Montréal and not at home in Lebanon is fraught. He frames the album around this experience in the liner notes: “Zaytoun was born at a time of heavy strife and internal conflict. My voice felt lost. It didn’t know where it belonged. Though I may have trained my voice in one genre, my heart felt like it belonged to another. Though I was carving out a life on a different continent, my heart belonged somewhere else. Zaytoun is all of these things combined. It joins the heart and soul of my Arabic roots with my love and dedication to Baroque music.”

Through interpretations that blend idioms from seemingly disparate musical cultures, Zaytoun, as Haidar writes, “highlights the natural connections between what we generally view as separate worlds.” Much like Haidar himself, Zaytoun is unabashed in its approach to music-making, but it’s an approach that’s sensitive and inviting.

For Haidar, all of the pieces on Zaytoun have one thing in common: he loves to sing them. His repertoire selections, European and Arab alike, developed organically over a period of several years. “About three years ago I started saying out loud to family and friends that I wanted to record an album. Any time I would think of a song that I love, even something I was just humming or singing casually at home, I would enter it into a document. And then suddenly I had this rep list.”

In 2024, Haidar chose to dissolve a professional relationship with an ensemble that had regularly offered him work, as he felt that some of his moral values were not shared by its artistic leadership. For a full-time freelance singer, this kind of decision bears significant financial consequences. “I was feeling insecure about how I was going to make up that income,” Haidar admits. He poured any spare time into a grant application to the Canada Council for the Arts, which funded Zaytoun in full: “As freelancers, we’re waiting for people to hire us. In a way, they’re in charge of our monetary destiny, let alone our artistic destiny. Suddenly, I had agency over some of my work, and that was very powerful,” he says.

In his first stint in the director’s seat, Haidar intentionally created conditions that would invite participation from his musical collaborators and grant them agency in the creative process. This began with acknowledging that participation in a cross-cultural project is a big ask. For example, getting an oud player to incorporate ornaments from a written (rather than oral) tradition, even when your oud player is as open and flexible as Abdul-Wahab Kayyali, who found the challenge of playing in a new style to be “very rewarding,” is still asking a lot.

Understanding that a cross-cultural project would require extra-ordinary labor, Haidar insisted on extra-ordinary labor conditions. “Freelance musicians in Quebec are represented by labor unions,” Haidar explains. “But union contract minimums in Quebec are very low, and almost all organizations pay you the minimum.” In his grant application, Haidar made the case for paying the participating musicians a much higher fee than the union standard: “The expectation was for them to show up in a way that they wouldn’t show up to just another rehearsal. This was a collaboration. I wanted their input.”

And he got it. Throughout the project, musicians versed in one style modeled practices for musicians versed in another style. The team conscientiously blended their expertises to achieve a balance that would not, as Haidar puts it, “change the integrity of a piece or impose a character that was not already there.”

Musicians versed in one style modeled practices for musicians versed in another

If you were to start and stop Purcell’s “Music for a While” in a random place, for example, you may not realize that you were listening to a crossover album. Cellist Amanda Keesmaat plays the opening statement of the ground joined at the very end by oud player Kayyali, who sounds just one note at a time, leading Keesmaat into a quintessential Baroque cadential figure. Unless you are intimately familiar with the timbres of European lute family instruments, it may take some time before you realize that the plucked instrument you are hearing is not the one that you expect. As the piece goes on and Abraham Ross joins on harpsichord, Kayyali begins to add melodic flourishes that draw from Arab musical traditions, which Haidar responds to with similar flourishes in the repeat of the opening text.

Flourishes aside, it is hard to imagine that Haidar, Keesmaat, or Ross would play this piece differently as part of a traditional European Baroque ensemble. The Zaytoun musicians do a remarkable job of bringing the natural compatibility between musical traditions into focus with a sense of ease. This degree of sensitivity and subtlety that pervades Zaytoun is one of its greatest achievements and perhaps one that harkens back to the album’s origin. “I wasn’t trying to exaggerate something that’s not fitting,” remarks Haidar about this subtle cross-cultural alchemy. “It all felt normal because that’s how I sing at home.”

These musical values guided the recording process as well. Many classical albums are recorded with all the musicians in the same sonic space, which is carefully selected for its acoustic. But to achieve a degree of subtlety that could be shared by instruments as loud as the cello and as soft as the oud, Haidar chose to record the album in a studio setting, where musicians record from separate sound booths and hear each other through headphones. “I wanted the color palette to be as wide as it could be,” he explains.” This recording process was particularly helpful for the Arab folk songs on the album like “Zourouni.” “I wanted it to be easy, like we’re just sitting together in a living room and someone pulls out the oud and then you start singing.”

As project director, Haidar saw Zaytoun an opportunity to practice a kind of leadership that mirrors a musical ethos of ease and invitation. “I find Western classical music to be quite rigid,” says Haidar, who feels that a musical culture obsessed with technical perfection can hinder possibilities for artistry. “I often feel like we’re just trying to tick boxes. ‘Oh. I hit the note, I was in tune. etc…’ Of course I have to be in tune, in time, and sing well, but this album was a good opportunity to step into a playground a little bit more.”

In this “playground,” the Zaytoun musicians embraced opportunities to move past their expectations about what a certain piece “should” sound like. Violinist Tanya LaPerrière, found these opportunities to be particularly rewarding, noting that her “favorite part [of the project] was the artistic freedom.”

Zaytoun offers this same freedom from expectations to its listeners. For example, listeners familiar with the traditional Palestinian song “Ya Taleen” might be surprised by the cello, tenor, and bass vocal accompaniment in Shireen Abu Khader’s arrangement, which Haidar commissioned for this project. Similarly, hearing “Erbarme dich” from Bach’s St. Matthew Passion sung by a tenor, played with Arab ornamental figures in the violin obbligato, and accompanied by just four instruments, will certainly subvert some listeners’ expectations.As Kayyali remarks, “Music is music regardless of genre, period, classification, or whatever box people want to put it into.” In some ways, asking “what can I bring to this piece in this new context?” rather than “how should this piece sound?” opened up possibilities for expression. This was certainly the case for Abraham Ross, who says that in his experience, “a program that draws on several styles or sources can more easily bypass the boundaries we often put on our own music. In the absence of such an exclusionary framework, stylistic distinctions become secondary to the tasks of affect, emotion, and communication.” These are the tasks that rise to the surface of Zaytoun.

“When you’re someone whose home is a home you have not been allowed to live in, you begin your search for your roots. As an Arab immigrant, life continues to be a journey of exploration of home, of belonging,” writes Haidar. Zaytoun will be available on all major streaming platforms. Despite the very personal nature of this project, its standing within the timeless global tradition of the “artist in search of self” brings forth universal themes that any listener can latch on to.

Ashley Mulcahy is a mezzo-soprano active as a soloist and ensemble singer. She also co-directs Lyracle, a voice and viol ensemble. For EMA, she recently wrote about church-bell change ringers as math and sport.