From the Publications Director: this column was first published in the May 2025 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

There’s an old joke about the social sciences where the exam questions are the same year after year but it’s the correct answers that change. The early-music field isn’t so different, where there’s a fundamental ambition — how did it sound when it was new? — but the ways in which that’s presented, and how it comes across for the listener, seem to change with each generation.

Nicholas Kenyon, in a lucid forward to Early Music in the 21st Century, edited by Mimi Mitchell (Oxford Univ. Press, 2024), summarizes a basic tenet of today’s historical performance, which went from an emphasis on “exactness of text” to, more recently, “understanding that a performer’s creativity can and should be shaped by many elements beyond the notes on the page.” Indeed, “it is the tension between the contexts of the time and the contexts of our own day that can be most fruitful in the ever-shifting dialogue between performer and audiences.”

A bit of that tension is found, unapologetically, in this issue [May, 2025] of EMAg. While knowledge needs to be shared to tell a meaningful story, there are also details to withhold to present a more nuanced, perhaps more equitable, argument for our own time.

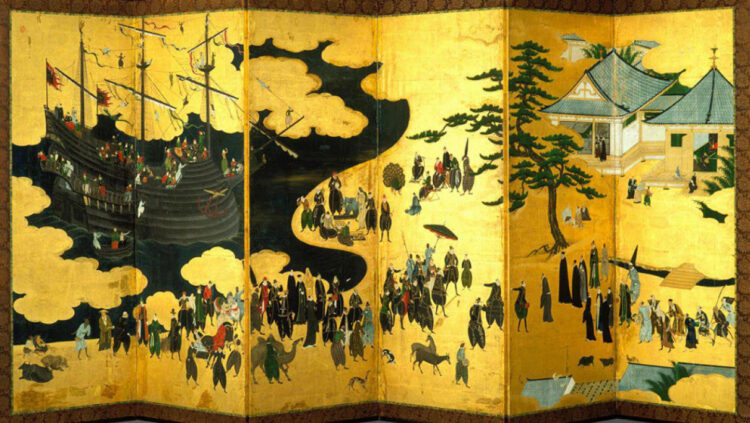

Boston’s Lyracle ensemble, to take one example, created a program about the Tenshō Embassy, a group of Japanese boys, students at a Jesuit missionary school, sent on a tour of Europe in the late 16th century. Italian and Iberian Jesuits wrote a lot about these events; the boys themselves remain silent. “We know the names of most of the authors of our selected passages,” writes Lyracle co-director Ashley Mulcahy, but in crafting a narrator’s script for the performance, “we chose not to include them since our goal was to emphasize the experiences of a group of people whose names remain mostly unrecorded. We also chose to exclude passages that make overt value judgments on non-European peoples and musics.” Lyracle’s approach to historical performance is a piece of our own time. Undoubtedly, performers of a different generation will make very different decisions about why and how they present musical history from the distant past.

Kenyon’s fertile essay goes on to ask a series of biting questions that may help frame other discussions about early music’s future. Some of them come as hard truths for our educational systems — another topic found in this EMAg issue. “As the period-style performance of the Baroque and then the Classical repertory became more professionalized, more skillful, better prepared, and more confident,” Kenyon asks, “did early music turn into just another product?” In short, has our acquiescence to the marketplace created a common performance language — an obvious artistic compromise, the sort of thing 20th-century pioneers disdained about products of an earlier age?

Yet with what Kenyon calls “absorption,” where the values of historical performance have been largely accepted by the wider classical world, at least superficially — e.g., your local symphony orchestra offering Messiah and Mozart with reduced forces and a lighter touch — “There is now a question as to whether there is really any need for early-music specialists and period-instrument performances anymore, since this coming together has taken place.” He calls this “the second age of the modern early-music revival…moving past polarization toward reintegration.” Our future, he suggests, should be as the research-and-development wing on the wider early-music landscape.

What? If you breathe the air of historical performance, this is heresy. And his use of that phrase, “any need for early-music specialists,” has an ominous ring.

Indeed. In this issue, “The Ups (and Downs) of Collegiate Early Music” touches on HP’s heady growth from a half-century ago, where young musicians and scholars entering the field could consider themselves rebels and part of the counterculture. The art is still flourishing with wonderfully high performance standards and a rapidly broadening repertoire. Alarmingly, despite these successes, new recruits are often scarce.

Even as period performance seems to be thriving in many corners of America, the future of early-music education at the collegiate level looks complicated. While a few schools are adding students and degree programs, others are retracting, retrenching, or going dormant.

“The more full-time faculty members you have and the fewer students, that doesn’t look good in terms of bottom lines,” says Dana Marsh, director of Indiana University’s Historical Performance Institute. “That makes it look expensive for the school. That’s kind of the straight-ahead truth there.” If enrollment numbers are a coal-mine canary, we can be sure the tensions built into our current early-music revival will multiply. What comes next?

Pierre Ruhe is publications director of Early Music America