by Anne E. Johnson

Published November 9, 2025

A new wave in musicology: Breaking our reliance on notation and documentation, and open to the experiences of the senses

Two monkeys sit face to face, their tails wrapped around a tree branch. At closer inspection, you can see a hole in each monkey’s neck. Blow into one end of the branch, and you’ll hear not just a double whistle, but layers of other sympathetic pitches, forming an ethereal tone cluster. The monkeys and branch are ceramic, based on an Andean artifact from hundreds of years ago. It’s adorable, and it sounds beautiful, but Felipe Ledesma Núñez sees in it a larger significance.

“We have this very ridiculous way of understanding history: That there was nothing, then the Spanish came, and they began culture,” says Ledesma Núñez. He grew up in Ecuador and, as young student, started wondering why the perspective of his own ancestors wasn’t represented in the music curriculum. He has made it a goal to construct a whole new approach to history in general, and music history of his native region in particular — a history not centered on the colonists.

He recently finished his doctorate in historical musicology at Harvard, with a dissertation exploring his interpretation of manuscripts from far-flung Andean villages. He’s started a fellowship at Yale’s Institute of Sacred Music, where he hopes to inspire students and colleagues to reevaluate the essence of music scholarship.

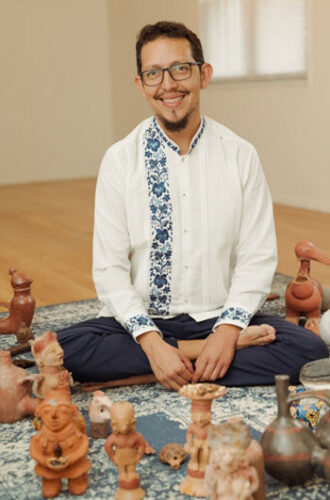

At the root of his new approach is breaking our reliance on musical notation and written documentation and being open to the experiences of the senses. To demonstrate, Ledesma Núñez holds up another Andean ceramic replica, this one a small, simple clay whistle. “You can still find these in backyards. This is the sounds we were making. I want people to see the deep history of who we are. And that history is not in the past; it’s cyclical. That’s how Andean time works. History is many times at the same time.”

He says he’s “trying to figure out how to write a history that will not be about just cathedrals.” In this, he’s been especially inspired by Columbia University scholar Ana María Ochoa, who “opened my ears completely” to the idea that “you can actually study music from outside of notation.”

For his dissertation project, he visited archives and villages, reading manuscripts left by missionaries and colonists in the Andes. Many of them, he says, are “very violent documents.” He had hoped to run across mention of music by the Indigenous populous. But “there was nothing,” and he was stuck. Then Kate Van Orden, his dissertation advisor, suggested, “‘Why don’t you read these as if they were not written in Spanish? Read it as a polyglot.’ After that advice, then I found it,” he says. “I found three words in a manuscript.” They were in a dialect of the Quechua language.

The manuscript, from 1662, contained several other groups of words, which turned out to be pieces of a puzzle. “That’s where my musicology training came in very handy,” he recalls. “I was thinking how medievalists can piece something together from nothing. Using that process, I was able to paste together all these fragments of Quechua and build a song.”

This was not just any song. “As far as I know, this is the earliest known song we have about the Andes. It was a song for an ancestor called Coya Huarmi, who had come from the sea and traveled different places. She was bringing flowers of lucuma and guava. She was well dressed, well adorned, a respected figure. They made all these dances about her, and they brought her to harvest. I realized that this ancestor was not only alive, but she was the first ancestor, that she was Eve.”

Ledesma Núñez eventually became convinced that Coya Huarmi was herself made of ceramic. “I realized that the ceramic spoke. And that people could understand what she’s saying, and that she was speaking at particular times, when she was placed near a water fountain. She would speak when filled with water.”

Coya Huarmi was, he believes, a ceramic whistling bottle. “These are Andean artifacts that have two bottles connected and they have whistles inside. If you put water in and you move it, it sounds like a human breathing and singing. It’s a human voice. It’s unbelievable.” Such artifacts are fairly commonplace, but archeologists have not been able to figure out what they were for. “I found it through sound,” believes Ledesma Núñez, “by listening to them.”

In order to do that, he experiments with his own replicas. He studied ceramics with Genaro López and Daniel Mesones in Ecuador and Samuel Tejeda Ramirez and Gilberto Chávez in Mexico.

His discovery was made possible by his willingness to move beyond what is written in documents and the widespread scholarly dependence on musical notation. “I’m getting the sense that this is not a problem of musicology only, but this is a wider problem in the humanities, in the sense that we are privileging symbolic systems of knowledge, the written word. And those kinds of systems are ill-suited: They cannot carry sound.”

This new perspective allowed him to think like a 17th-century Andean, to whom “the separation between human and non-human makes no sense, between the living and the dead makes no sense. I think those are lessons that are impossible to see when you’re using symbolic language. But you use this” — he holds up a whistle — “and it’s obvious.”

It’s an understatement to call Ledesma Núñez’s approach to history interdisciplinary. “I started taking classes in every department I could,” he says. That included Romance languages, history, paleography, and linguistics. Once he found the first fragment of the ancestor song, he dived into Quechua and related languages in Ecuador. And, of course, he studied ceramics, so he could replicate the instruments.

Despite his own peripatetic studies, he cautions against compartmentalized learning: “Disciplines put up borders and make things impossible. Disciplines give you very strong guidelines, and if you stick inside of those guidelines, you’re not seeing. I learned skills that I needed to deal with a knowledge that was very specific. And once I learned those skills, my investment in the discipline was done.” He adds, “You have to learn different tools and techniques in the service of the knowledge.”

That knowledge seems to awe him. “I found Eve in the archive, singing, and I know how to build her form, how to build her voice. I think this is knowledge that came from the outside, in a way. Knowledge that chose me. And I’ve just been a sort of medium.”

Yet van Orden, his dissertation adviser, gives him credit: “It has been very impressive to see him continually retool his methodological approaches in ways increasingly attuned to his subject matter. His turn to ceramics is one example of this desire to help past voices sound on their own terms.”

The Sounds of the Ancestors

His commitment to recreating sonic history is intense. He holds up one of his whistle replicas, which is not yet functional. The original artifact, he says, “can do about 200 different sounds. I’m trying to understand how the acoustic mechanism works because it blows my mind.” And then there is the double-whistle shaped like two monkeys on a tree. The original makes two pitches and one battimento tone, but in his replica, “I don’t know how, there’s harmonics to the battimento, and you can hear six or seven different sounds coming out of nowhere. I don’t think acoustics has a vocabulary to explain that.”

Such revelations are the point of the exercise. “If you really want to study sound from the ancestors that lived on this earth, you have to go to their sources.” He indicates the monkey whistle. “You can write as many words as you want to about this, but the sound of it makes them alive.”

He has presented this idea to students with good results. “The grad students, the ones that get it, their ears are open, and they’re having very different conversations now.” His students at Yale will get hands-on experience making their own ceramics. That’s partly why he was granted the fellowship at the Institute of Sacred Music, says the program’s associate director and fellows coordinator, Eben Graves. He anticipates Ledesma Núñez’s multi-faceted approach to be “of interest to many studying the interdisciplinary field of ritual, religion, and the arts,” especially those intrigued by “the overlapping spheres of musical sound and material culture in Andean contexts and beyond.”

Ledesma Núñez knows he’s lucky to have the chance to do this work. “Academia has been extremely supportive. They get my project.” Yet some reactions to his work have been frustrating. “When I was starting to share my findings from the manuscript, the commentary on my writing would be something like, ‘Who are you citing?’ The impulse is always, ‘Where do I classify you? How do you fit into Academia so I can think of you in the narrowest possible terms?’ And they are completely missing the point.”

On the other hand, some fellow scholars understand his written work but don’t see the purpose of the reconstructed ceramics. “They don’t get the living quality,” he says. “These are our ancestors, and they’re alive, and they’re with us. They need to be honored and respected. Not just written about.”

The key, Ledesma Núñez believes, is to take a completely different approach to history, beyond written language and other symbols. “If people would just disconnect from that and use their bodies, their senses, their ears, their hands, it would open them up to a whole other category. It would deconstruct the dividing of the disciplines and the stigma of seeing the Americas as someplace that doesn’t produce anything, or that only produces through error.”

He wants his own ancestors to be understood for who they really were. “We’re not a history of the trauma of colonization,” he insists. “No, we have a very long history that keeps going and that we can be a part of.”

Ledesma Núñez’s ceramic sound sculptures are currently on view at Yale’s Institute of Sacred Music, where he will also have a solo exhibition in the spring.

Anne E. Johnson is EMA Books Editor and frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently wrote about pioneering American folklorist Francis James Child.