by Max Keller

Published December 7, 2025

‘Paradoxically, historical instruments bring a quality of timelessness‘

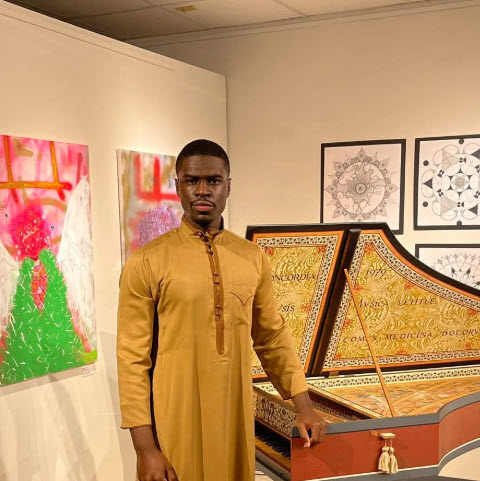

In one rousing scene from a much-lauded work of music-theater, The Faggots and Their Friends Between Revolutions — which had its North American premiere at New York’s Park Avenue Armory last week and runs through Dec. 14 — a boom box and disco-inspired strobe light are interspersed with theorbo, harpsichord, and viola da gamba.

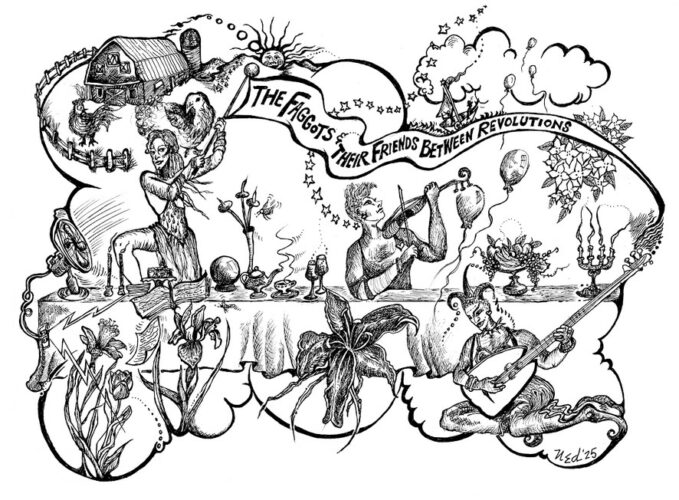

This juxtaposition of old and new, reverent and profane, characterizes the campy, cabaret-style work created by stage director and writer Ted Huffman and composer Philip Venables. It’s an adaptation of the 1977 queer cult-classic by Larry Mitchell, told as a series of vignettes, with illustrations by Ned Asta. The book — part myth, part manifesto — tells of the empire of Ramrod, inhabited by “the men” (straight men), “the faggots” (gay men, mostly), and “their friends” (everyone else).

Huffman and Venables’ show has garnered acclaim — and a lot of social commentary, especially about that provocative title — since its debut run two years ago in the U.K. and Germany as well as at the Aix-en-Provence Festival, known for its substantive and imaginative open-air opera productions in the South of France. (Huffman was recently named the Aix Festival’s artistic director, to start next month.)

Less attention has been paid to the production’s use of Baroque instruments alongside modern ones. At the start of Tuesday’s performance, along the perimeter of the Armory’s stage, I spotted Baroque violins, viola da gamba, theorbo, lute, Baroque guitar, Hammond organ, harpsichord, upright piano, Baroque harp, Medieval harp, accordion, saxophone, and flute. What were these historical instruments doing here?

My sense is that these instruments take on meanings beyond what Huffman and Venables initially imagined.

Ben Miller, in a 2023 article for the New York Times, wrote that mid-1970s gay communes such as Upstate New York’s Lavender Hill, upon which Mitchell’s book is based, put Baroque music into their mix, citing a diary entry mentioning a “visiting harpsichordist.” This makes sense considering that this counter-cultural era also saw the rapid growth of the early-music revival.

But for Huffman and Venables, the decision to mix Baroque and modern instruments was more instinctive than strictly conscious. “We kept being drawn to the idea somehow,” Venables told me recently. Indeed, as they were planning Faggots and Their Friends, Huffman had just directed Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea with a period-instrument ensemble at the Aix Festival, where they “felt the music was being made with such life.”

That sort of music-making, the composer observed, was all about peer-to-peer, rather than peer-to-conductor, relationships. The creative team were drawn to the idea of how Baroque instruments could express “coming together” or “community organizing.” The language of Baroque opera, Venables added, lends itself to supernatural themes like “gods and fairies.”

This “communal” feeling is reflected in the Park Avenue Armory production. At one point, everyone in the cast picks up a violin and plays open strings. There is even a sing-along with the audience.

“We wanted a kind of music-making that felt almost improvised, devised, extemporized,” Venables told me. Instrumentation was highly dependent on the casting process: “I tried to make the score a bit open,” with instruments not strictly defined.

The resulting “hodge-podge mix of instruments,” Venables said, comes to stand for “allyship across different communities and identities.” The blurring boundaries between periods and genres acts as a metaphor for “passing” or “code switching” — moving between gender or identity expressions.

Here a dance can turn seamlessly from a Baroque gavotte to a Latin bossa nova. Venables compares such transformations to “putting on different musical costumes.” Elsewhere, Kerry Bursey, a pure-voiced tenor, accompanies himself on lute, Dowland-like. Gambist Jacob Garside plays rolled chords and chafing dissonances, fingers tapping the fingerboard. Fiddler Connor Gricmanis, wearing booty shorts, plays a sea shanty. Countertenor Collin Shay plays theorbo and sings with Handelian lyricism. Although modern instruments are considerably louder than their Baroque counterparts, everything and everyone was amplified; instrumentation and voice types posed no problems in the stadium-sized Armory.

Faggots and Their Friends tells of an imagined past as well as utopian future. “It’s been a long time,” soulfully sings Mariamielle Lamagat, “and the faggots are still not free.” The faggots “love to perform for each other,” recites performer Kit Green in a slinky red dress, that way “the past is never lost.” Elsewhere, Green informs us that, “At night, they sing and dance and fuck” — a declaration of sexual freedom which turns poignant with our knowledge that the devastating AIDS epidemic was just around the corner at the time of Mitchell’s writing.

“Paradoxically, historical instruments bring a quality of timelessness,” said Venables, “that feeling like you’re reaching back in the far depths of the universe.” Venables’ use of Baroque and modern instruments engages with “Queer Time,” the idea that queer people might experience time differently or non-linearly.

Their musical setting has another, unintentional, effect. The antique instrumentation is an auditory analog to Asta’s fantastical illustrations, which are integral to Mitchell’s book. Asta’s drawings, inspired by the art of Victorian-era Aubrey Beardsley, feel out-of-time, surreal, almost alien. Venables and Huffman’s sound-world is just as intricate and evocative.

The Armory program booklet features a new illustration by Asta, dated 2025. One corner shows a violinist with a pixie cut. In another corner, a draggy Harlequin plays the theorbo. The instrument’s long neck threatens to go off the page, and into the “real” world.

Max Keller writes about classical music and queerness. Their work has appeared in the New York Times, the Nation, the Brooklyn Rail, Parterre Box, as well as on their substack Poison Put to Sound.