by Pierre Ruhe

Published December 21, 2025

What were EMA’s most viewed online stories in 2025? Almost all were first published in our weekly E-Notes newsletter. It is often social media, however, that plays the biggest role in which articles are widely shared, get a big boost in readership, and break into our annual Top 10. And it’s worth noting the broad range of topics on this year’s list, from artificial intelligence and early-music education to church-bell ringers, English country dance, and a singer’s personal take on seeing representation (and being that representation) on stage.

No. 10: Nevermind’s Goldbergs, a Garden of Musical Colors

Harpsichordists will tell you, with no hesitation, that the Goldberg Variations are the greatest gift given to us by J.S. Bach. But in this imaginative and deeply satisfying new recording, the French period-instrument quartet named Nevermind reveals the chamber music inherent in the music. Surprisingly, harpsichordist Jean Rondeau and his three colleagues find truths in the music that are beyond the reach of the original.

No. 9. Michele Kennedy: On Representation and Joy

Soprano Michele Kennedy writes about two profoundly moving experiences in her musical life. ‘For aspiring young musicians — especially for those who lack access to live performances — seeing their own image reflected back from the stage can be life-altering. It can awaken music in their senses in a lasting way that nothing else can simulate.’ And, as an artist, ‘being that example for others, only more conscientiously than before, I now understand how profound its impact can be…when we delve deeply into it, bare our hearts and get goosebumps and feel our blood pumping through our veins with the intensity of this work, we know that we are truly getting somewhere. It is never easy, but when it’s done in a safe and supportive community, it is profound.’

No. 8: English Country Dance, an American Pastime

With Jane Austen fans celebrating the author’s 250th, English country dance is again having its moment. The art form is like taking a walk through the history of social dance and music, much of it based on Playford’s The English Dancing Master. Always a fun night out, it today attracts a spectrum of participants and is never better than when backed by an early-music band. ‘Each time you go around the form of AABB, a different person takes the lead. You have to know you’re next and jump in. And you have to deliver, right then! The dancers are all moving but you can’t see them because you’re figuring out what you’re doing — but it’s incredible.’

No. 7: Change Ringers Find Math and Sport in Music

Change ringing started in North America in the 1740s. It’s a musical team sport, it’s math for musicians, it’s an exercise for engineers. The ringing of the bells in an ordered sequence, as a piece of music, is a historical hobby that’s been growing in the U.S. in recent decades. The time that it takes for each bell to fully rotate makes playing melodies impractical. ‘To get the bells to be really loud, they actually ring from mouth up all the way back around to mouth up.’ Because it takes a while to ring the bells that way, they don’t ring tunes, they ring patterns. We checked in with the MIT Guild of Bell Ringers in Boston to peal a bell ourselves.

No. 6: Can AI Decipher a Manuscript Better than You?

Stuck on sloppy handwriting from the 17th century, the cellist and viol player Kivie Cahn-Lipman (at left, depicted by AI in a hallucinatory moment) recently turned to artificial intelligence to help solve a motet’s textual problems. He had initially forced himself ‘to explore ChatGPT the semester I taught a writing-intensive early-music history class because I wanted to prevent forbidden use of AI by learning what AI-generated papers might look like.’

Despite many negative impressions, ‘the process of exploring ChatGPT opened my eyes to its potential’ as a valuable research partner.’

No. 5: ‘Soul’ Between the Notes: Grete Pedersen on Historical Performance

Norwegian conductor Grete Pedersen is in demand everywhere just now. She’s principal conductor of the Yale Schola Cantorum starting in 2026 and has been at the helm of the idyllic Carmel Bach Festival for the past three seasons. In a conversation along Carmel Beach, she talked about her organic approaches to early music.

No. 4: The Ups (and Downs) of Collegiate Early Music

Historical performance is on an upswing across the U.S., and standards have never been higher. But the future of the field is not so clear for the next generation. There’s some growth at the collegiate level but, alarmingly, more than a few losses. What’s the national picture?

No. 3: Bach in the City, Chicago’s Newest Period Ensemble

In September, a new period-instrument ensemble, Chicago’s Bach in the City, launched its inaugural season. Artistic leaders Richard Webster and Jason Moy, veterans of the Chicago classical scene, have secured dedicated funding to give the group staying power. ‘Suddenly, now, we have a critical mass of period-instrument players attracted to Chicago, and that was not true a decade ago.’

No. 2: El Mesías: Messiah for a New World

Bach Collegium San Diego, led by Ruben Valenzuela, finds acclaim for their El Mesías project, a translation of Messiah into Spanish. And why not? Handel himself altered his music to adapt to new contexts, new languages, new audiences.

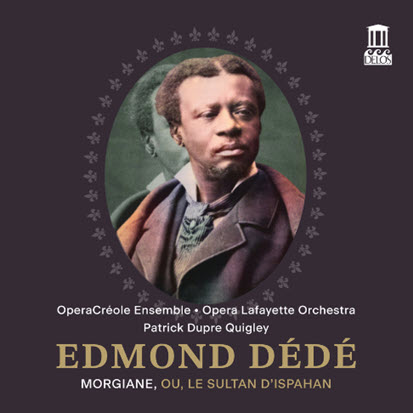

No. 1, the Most Viewed EMA Story of 2025: Edmond Dédé, America’s First Black Opera Composer

In February, New Orleans’ OperaCréole and D.C.’s Opera Lafayette collaborated on a world premiere, 138 years after the music was written. Edmond Dédé fled antebellum New Orleans and ended up in France, where he was a successful conductor and composer. His grand, four-act opera Morgiane, with hummable tunes and a sensational plot, however, was never performed or recorded, till now. It is perhaps the oldest known complete opera by an African-American composer. ‘People will be shocked that they’ve never heard of this composer. The vocal writing is virtuosic, the orchestration is unbelievably colorful.’ Dédé’s score ‘combines the tunefulness of what you think of from New Orleans with the prevailing French operatic forms of the time.’