The all-female Ospedali musicians have been hidden twice: once behind the grills in their own time and once behind Vivaldi in ours. And since at least Vivaldi’s era, the women who performed at the ospedali have become a fantasy of winsome young orphan girls.

This article was first published in the September 2025 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

Tempesta di Mare’s Hidden Virtuosas project, performed in November 2025, includes a 20-minute cantata, Ecce nunc, composed by Agata Cantora, a ward of the Ospedale della Pietà

It’s unlikely but true: In the 18th century, the toast of Europe’s musical connoisseurs was female singers and orchestral musicians from, of all people and places, Venice’s charity institutions for the sick and destitute. Those institutions — the ospedali, or hospitals — offered an ambitious schedule of public concerts entirely performed by women. And this in an era when women instrumentalists were not allowed to play in public almost anywhere else.

These all-women orchestras boomed, becoming an international tourist draw for Venice on a par with its lagoons and gondoliers. Visitors couldn’t get enough, darting in and out of the four ospedali concert halls, sometimes two shows a day. In 1771, Charles Burney, the English critic and well-traveled chronicler, raved over these riches, over performances that so pleased him in “both the composition and performance, that in speaking of them I shall find it difficult to avoid hyperboles.” He called Rota and Pasqua Rossi, two singers at the Ospedale degl’ Incurabili, “the nightingales” who “poured balm into my wounded ears.”

The loophole that the Governors of the Ospedali had discovered was that their all-girl bands could play in public as long as you couldn’t see them. So these celebrated ospedali musicians accustomed themselves to singing and playing — even the tempestuous, highly dramatic repertoire of the Italian high Baroque — holed up behind metal grills in specially designed galleries high above floor level.

Which the audience loved. The girls behind the grills imparted that special Venetian mystique. Fans sent home reports about the uplifting experience of an ospedale concert, the sweet melodies that wafted overhead like mist or clouds. It was, as Jean-Jacques Rousseau described the experience, like being serenaded by “angels of loveliness.”

Beg to differ, we say today. They were, of course, not angels. Nor were they the kind of idealized, disembodied female their audiences dreamed of. They were flesh and blood women. Many bore the external signs of mortality in scars from disease (smallpox was everywhere), poverty, or the conditions present at birth that caused their parents to reject them in the first place. And although history ignored their voices in favor of the celebrated men around them, we now know that they were also highly trained, ferociously talented, and deeply ambitious.

Twice Hidden

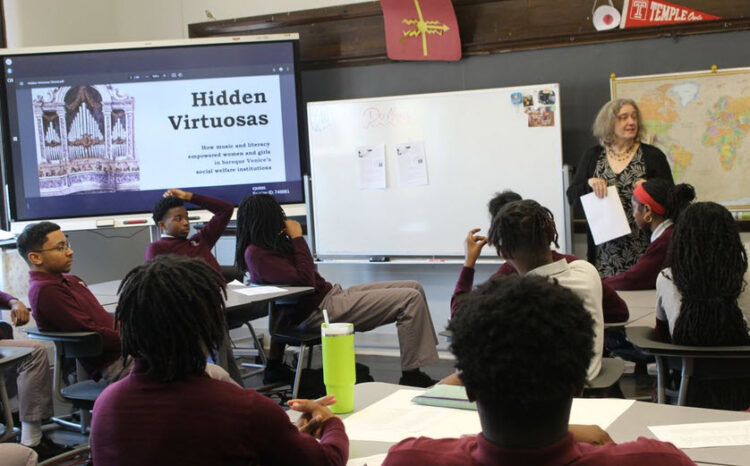

One April morning, Gwyn Roberts, co-director of Philadelphia’s Tempesta di Mare and a recorder and Baroque flute player, is telling the story of the ospedali to an 11th-grade history class at a local high school, Girard College. She’s just handed out a roster of musicians who performed at the Ospedale della Pietà in 1739. It was a long list that year, 69 of them. She reads from it:

But if you take a look, first of all, you’ll notice that they don’t have last names, right? They didn’t go by last names because they were all abandoned as babies, usually by their mothers. They had first names.

So Angletta is a violinist and a singer and a teacher because they were also teachers of each other. She’s our oldest at age 73. Ah, our youngest is Luigia, she’s a violinist at age 12…

Roberts shows the students an old engraving of the Ospedale della Pietà’s exterior and points to the small window facing the canal — a literal drop box for women to abandon their infants. Put the baby inside, pull the rope that rings a bell, disappear into the night.

It’s still early, first period, and some of the high schoolers are nibbling on pieces of breakfast. But they are rapt. “They just spoke to me,” Roberts says about her own realization of the women of the ospedali. Some of those abandoned babies grew up to become internationally recognized musical virtuosas. She’s been telling their story for months, lecturing at music festivals, coaching her students at Peabody Conservatory and the University of Pennsylvania, and providing commentary to audiences at Tempesta concerts of ospedali music. Whatever the audience, it never fails to elicit strong emotions.

For Roberts, it’s passion with a purpose: She’s seeding interest in these women ahead of a major event in Philadelphia called Hidden Virtuosas. In November 2025, Tempesta di Mare will offer concerts, programs, a scholarly symposium on recent research and changing attitudes, and community outreach — including the participation of the choir of Girard College, where she was speaking in April. Girard College itself was founded in 1848 by a Philadelphia philanthropist as a full-scholarship boarding institution to educate poor and fatherless boys (today it is co-ed and K-12).

Gripping personal narratives, a triumphant redemption story, great music. This is the kind of compelling subject that early-music groups are turning to as they expand their scope. Off-the-beaten track subjects like this, with plenty of present-day appeal, encourage audiences enthusiastic about Bach and Handel to branch out to other parts of the Baroque musical world. And the musicians associated with the Venetian ospedali constitute a Who’s Who of 17th- and 18th-century greats — the “best masters of Italy,” Burney wrote — many of whom are all but who unknown today.

And, of course, there’s Vivaldi.

Here’s our wind player, anybody a wind player here? This is my spirit animal here: This is Pellegrina. So Pellegrina was both an oboe and recorder soloist. A lot of Vivaldi’s oboe parts and recorder parts are written for her and her companion-slash-student, Susanna.

Vivaldi was famously connected to the ospedali system, specifically the Ospedale della Pietà. It’s just that he may not have been as central as we are generally led to believe. The Pietà orchestra was at full force before Vivaldi’s arrival and remained so after his departure. The orchestras at the other ospedali were equally admired; he had no involvement with them at all.

Much of Vivaldi’s popularity is connected to The Four Seasons, those electrifying violin concertos whose reemergence in the mid-20th century — after a couple of centuries of obscurity — made Vivaldi a breakout star of our current early-music revival. Yet in the zero-sum game of historical hindsight, his prominence had the unfortunate consequence of eclipsing the reputations of his Venetian colleagues. The women who made his music possible are known by association with him — but have all too often become distorted into a kind of fantasy image of winsome young orphan girls. In some ways, the Ospedale musicians have been hidden twice: once behind the grills in their own time and once behind Vivaldi in ours.

Living Their Best Life

The ospedali story predates Vivaldi by centuries. The first and largest of the institutions that would field orchestras, the Ospedale della Pietà, was founded in 1346 to provide for illegitimate children. Three more followed, also established to serve the poor as a civic good: the Ospedale degl’ Incurabili, for syphilitics and sex workers; the Ospedaletto dei Derelitti, for the homeless; and the Ospedale dei Mendicanti, for beggars and orphans.

They didn’t start out as music schools. Their mission was to shelter their charges and prepare them to live meaningful lives. For boys, that meant training for trades. As the trades weren’t open to girls, they were taught domestic skills which included music. Eventually, music training for a selected few morphed into an increasingly demanding music program.

Jump ahead to the 17th century, when Venice had transformed from a manufacturing and trade center to a music-mad entertainment and tourism mecca. With a corps of trained musicians and new talent in (sadly) endless supply, the Governors of the Ospedali were sitting on a goldmine. They took full advantage.

Each of four ospedali established public concerts. They brought in a healthy income, particularly during Lent, when the ospedali could put on shows but commercial theaters could not. And they encouraged deep-pocketed donors. At the height of the phenomenon’s popularity, the Governors brought in outside male professionals, maestri di cappella, to shape the programs and train the wards in up-to-date, crowd-pleasing styles, creating music for them to perform. (Vivaldi was contracted for a concerto every two weeks, for instance.) In practical terms, however, the orchestras of the ospedali remained little patches of matriarchy in the middle of a resolutely patriarchal culture.

The teaching of the figlie del coro — these “daughters of the chorus” — became legendary. They trained themselves to high degrees of proficiency and they trained daughters from the city’s affluent families, too, for a fee, at what became known as conservatories; these outsiders would be eligible to join the cori by audition. At some point, the figlie del coro themselves could leave their ospedale by marriage or agreement, although frequently they were required to renounce performing in public after they left. The institutions tried to retain the most distinguished members of the coro, offering them advancement, income-producing opportunities, and special privileges. But many, by choice or necessity, stayed for their entire lives — singing, performing (often as multi-instrumentalists), composing, gaining mastery and seniority, and training generations of new musicians.

They brought in a healthy income, particularly during Lent, when the ospedali could put on shows but commercial theaters could not

We recognize the cost. The Governors were keenly aware of the razor’s edge on which their endeavor balanced. They went to all lengths to assure the public (especially donors) that they were fiercely protecting their charges’ virtue and chastity. The women residents lived highly restricted lives with rules and parietals that could be enforced by banishment or even in-house prison. Rules were relaxed for the figlie del coro of higher musical positions, some of whom had become celebrities — but only to an extent.

Women in History

Here is Agata Cantora. ‘Cantora’ meant she was a singer, right? She was abandoned as a newborn in 1712, wrapped up like a Christmas present, in red silk with all kinds of adornments around her, and a note saying, ‘I will reunite with her one day,’ which never happened. She was disabled, she had one finger on her left hand, a full right hand, one toe on her left foot, three on her right, and she was constantly sick throughout her life, which she spent entirely at the Pietà — she died at age 57.

But what is really fascinating about Agata is that she was also a composer. A full cantata by her, 20 minutes long, survives with enough music that it’s reconstructible.

The ospedali orchestras were effectively out of business by the end of the 18th century, although the Pietà orchestra held on until the 1830s. Many of the physical records of their operation, including most of the music itself, were lost — perhaps accelerated by Napolean’s invasion in 1797. Most Baroque-era music fell out of style in the 19th century. Memory of the orchestras faded.

When great swaths of Baroque music and historical performance styles were revived in the 20th and 21st centuries, Vivaldi’s importance in the ospedali was probably overstated. But in parallel, his fame has been a huge boon in raising interest in them. And new research and a focus on women in history have drawn early-music practitioners to explore the ospedali more deeply.

In recent decades, scholars have produced substantial research, and two in particular inspire much of the present activity. Micky White compiled the 1739 Pietà roster that Roberts mentions in Hidden Virtuosas. White’s articles, her book Antonio Vivaldi, A Life in Documents, and her contributions to the 2006 BBC documentary “Vivaldi’s Women,” have led to a major reexamining of musical life in the ospedali. The other scholar is Vanessa Tonelli, whose articles and her 2022 Northwestern dissertation, Figlie del Coro: Women’s Education and Performance at the Venetian Ospedali, 1670-1740, are considered a touchstone by many. Both scholars have consulted with Tempesta, and Tonelli will speak at the project’s symposium in November.

Some ensembles, including Tempesta di Mare, are programming Vivaldi works documented (or likely) to have been written for the ospedali. Several of these projects recreate the ospedali’s all-female orchestras, and some enlist low-voiced women to sing tenor and bass parts in the choruses — as was the original practice at the Pietà.

Others, including Tempesta, are performing the small body of work known to be directly associated with the women, like Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen from the Mendicanti, and Anna Bon from the Pietà, who went on to concert careers after leaving the ospedali; or Santa Tasca, who married out of the Pietà and became an international opera star; or Anna Maria, who never left the Pietà and for whom Vivaldi wrote many of his violin concertos. (There’s no documentation that The Four Seasons was composed for Anna Maria, but that assumption has made a great storyline for novelists.)

Tempesta will perform Richard Stone’s reconstruction of that 20-minute cantata for orchestra, chorus, and soloists by the Pietà’s Agata Cantora, her Ecce nunc (Psalm 133) in their November program. They’ll also present recently discovered vocal cadenzas: Chiara’s (from the Pietà) in a concerto by Antonio Martinelli; Fortunata’s (also Pietà) in a motet by Andrea Bernasconi; plus vocal music custom-written for Giovanna Cedroni (from the Mendicanti) by Pietro Domenico Paradies; and for Apollonia (Pietà) by Giovanni Porta.

Learning the Quirks

Tempesta’s works show how compelling, poignant stories like the Ospedali story can persuade even audiences normally wary of unfamiliar work to give it a chance. That’s Gwyn Roberts and Richard Stone’s ethic. They founded Tempesta di Mare over two decades ago to revive and explore 17th- and 18th-century music that had been lost, forgotten, or misunderstood in modern times, along the way presenting some 50 modern premieres and gathering a stable group of like-minded players and audience members willing to take the journey with them.

Three years of ospedali-related programs have allowed them to present such members of the Venetian branch of the renowned-in-his-lifetime-but-rarely-heard-now club as Cedroni, Paradies, Porta, Porpora, Veracini, Galuppi, Ferrandini, and Gasparini. This past May, audiences leaped to standing ovations, tears in their eyes, for arias by Leonardo Leo and J. A. Hasse performed by mezzos Gabriela Estephanie Solís and Meg Bragle. There’s a reason this phenomenon was so popular in its day.

For Tempesta’s musicians, even after decades of playing Vivaldi and Italianate Bach and Handel, these ospedali concerts have something new to teach. “What’s different,” says Tempesta concertmaster Emlyn Ngai, “is learning the quirks of these individual composers. They have personal idioms, their own moves. We can separate a standard pattern from an anomaly, something that’s different, a twist. It sets off a spiderweb of associations.”

Hidden Virtuosos, in November, will offer audience members their own chance to step into an 18th-century experience along with the musicians. To replicate the experience of an ospedali performance, musicians will be hidden from listeners’ view by a theatrical scrim. Later, the salon program will take place in an intimate-sized hall where musicians in the personae of ospedali figle will mingle with visitors, with Gwyn Roberts as Pietà oboe and recorder player (and kindred spirit) Pelegrina; violinist Karen Dekker as Anna Maria from the Pietà; mezzo-soprano Gabriela Estephanie Solís as Pietà-educated opera star Santa Tasca, and so forth.

Solís has performed in two of Tempesta’s ospedali shows and will be singing behind the scrim in Hidden Virtuosos. She’s thought a lot about what it means to bridge the distance between our present-day life and the music of the past. “We are not doing a reenactment,” she says. “I am not Santa Tasca and if I tried to be, that would be a disservice to me and the audience. What I do is take the information that I have and use it in what is my performance.”

And there is so much fascinating information in the ospedali stories, so much that is paradoxical: the deprivations, the limitations, the humiliations along with the possibilities, the freedoms, the rewards. As Ngai puts it, “there’s the amazement and the wonderment of people working under these conditions, being literally hidden from view. It’s almost an ethical or moral obligation to bring this out, to somehow treat those individuals the same way we would treat a Telemann, a Fasch, or some other figure we’re studying in depth.”

Which cellist Lisa Terry expresses in no uncertain terms. “When we dig into the secrets, into the true stories that are absolutely fantastic and interesting, I feel desperate to tell it, to get it out there.” She speaks for almost everybody who’s been connected with these projects: “We care about these lost people, these women who were hidden and then ignored.”

Anne Schuster Hunter is a writer, teacher of creative writing, and art historian in Philadelphia. www.anneschusterhunter.com.