What can we learn from a uniquely detailed record of five viols across three centuries of North American history? The Siege of Québec, in 1759, may explain why instruments were hidden in the Hôpital’s secret vault.

The viols’ journey tells us about Canada’s musical past, about how ‘ancient’ instruments are woven into new cultural fabrics, and about narratives of early-music revivals

The February 1919 issue of the Montréal music periodical La Musique carried a curious account of the happenstance discovery of a hoard of ancient stringed instruments in the Hôpital-Général de Québec, one of the oldest buildings in Québec City.

[In about 1860,] masons were employed to carry out repairs at the Hôpital. One day they encountered a wall that sounded hollow. Intrigued, the masons obtained authorization to demolish the wall and discovered behind it an ancient vault [“caveau”], just like the ones built in the early days of the Colony to hide provisions and necessities in case of attacks, first by [Indigenous warriors], and later, from the Anglo Saxons who had set out to capture Canada.

By candlelight, the masons found a number of pieces of woolen cloth that disintegrated at the first touch. […] Alongside these pieces of cloth lay a dozen six-string musical instruments, viols big and small from the factory of Nicolas Bertrand, of Paris. How long had these instruments been locked up like this? All we can conjecture is that they date back to an early importation from Europe to Canada.

As we’ll see, the subsequent adventures of five of the “caveau” viols have much to reveal about some of the earliest early-music revivalism in North America, including a journey from Québec to the American Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia in 1876 and an unlikely cast of opportunists, collectors, luthiers, and musicians.

The story in La Musique was part of a series titled Musique et musiciens à Québec: souvenirs d’un amateur by the historian, multi-instrumentalist, and composer Nazaire LeVasseur (1848-1927), a dynamo of the Canadian music scene during the decades surrounding the turn of the 20th century. LeVasseur had studied violin with another icon of 19th-century Québecois music, the luthier and violinist Joseph Lyonnais (1821-1889), whose son Roch would inherit his father’s luthiery business.

It is Roch Lyonnais, in fact, whom LeVasseur credits with revealing to him the story of the “caveau” viols. LeVasseur’s account continues:

At the time [of the discovery], there was a blind man, a very intelligent boy who played the violin quite well. The superior of the [Hôpital], a good woman no doubt, but who was not an antiquarian and not interested [in] worldly curiosities, gave [one of the small viols] to the blind musician. The fiddler, enchanted, regaled his world with all the scotch reels, hornpipes, jigs and cotillions from the repertoire of the day…But, finally, the violin didn’t suit him. He went to [luthier] Joseph Lyonnais, where he usually bought strings and rosin, to ask him to make his viola into a small violin. Just imagine a six-string viol in the hands of the unfortunate blind man! He had made up his mind to play on the four highest strings and ignore the other two.

[But] even for a skilled violin maker, turning a viola into a small violin is as easy as turning a contralto into a light soprano. Joseph Lyonnais finally persuaded him [that the conversion] was an impossibility and offered the fiddler a small violin in exchange for the viol. The deal was struck, and it was on this occasion the blind man told père Lyonnais the discovery of musical instruments at the Hôpital.

So, the fascinating tale of the “dozen” Bertrand viols discovered in the forgotten vault reaches us only via a long game of “telephone” from the lips of the Mother Superior to the blind fiddler to elder luthier Joseph Lyonnais to his son Roch and finally to LeVasseur, who published it in 1919, some 60 years after the purported discovery.

In fact, archival research over recent decades has corroborated many of the story’s details. The Siege of Québec in 1759, during which British troops surrounded Québec City for several months before the French capitulation and the ensuing transfer of New France to New Britain, may have provided an impetus for the concealment of the viols in the Hôpital’s hidden vault.

The Hôpital’s archives document the purchase of strings and fittings for viols from about 1740 to the late 1750s, when privations of the Seven Years’ War may have reduced musical activities at the Hôpital. One can perhaps understand how in a fantastical tale like this one — told and retold for decades — five or six viols might become “a dozen,” and a group of unfamiliar instruments from various hands might all end up ascribed to the celebrated Nicolas Bertrand, of Paris.

But the most compelling evidence surrounding the story of the “caveau” viols is surely the survival of the instruments themselves, five of which are currently known and traceable to Québec City in the middle of 19th century. The journeys of these five viols — two by Nicolas Bertrand and one each by Jean Villiaume of Mirecourt (often spelled Vuillaume), Antoine Cabroly of Toulouse, and anonymous — from the Hôpital to their current locations in museums and academic instrument collections have much to tell about the history of music in Canada, the adaptation and transformation of “ancient” instruments as they are woven into new cultural fabrics, and the unique and fascinating stories of people and objects that underlie narratives of early-music revivalism.

Terminology used by different communities over the centuries to refer to various European stringed instruments is notoriously fluid, often making it difficult for scholars to distinguish with certainty between references to members of the violin versus viola da gamba families. In the case of the “caveau” viols, however, the instruments themselves testify unequivocally to their identity as the latter.

For the viols from the Hôpital are not the only ancient stringed instruments known from the archives of Nouvelle France, though the origin of several “caveau” viols in the shop of Nicolas Bertrand — the most prominent French viol maker of the early 18th century — has attracted much attention over the last century. In their monumental La vie musicale en Nouvelle-France (2003), Élisabeth Gallat-Morin and Jean-Pierre Pinson describe how convent records in Québec give proof of numerous uses of viols in different monastic and liturgical settings. Sometime in the mid-17th century, the sainted French Ursuline nun Marie of the Incarnation (1599-1672) wrote about several of her indigenous charges, including at least one who was taught to play the viol:

Some time before [Agnes Chabdikuchich] entered the Seminary, she met [a priest] in the wood where she was cutting provisions. She had no sooner seen him than she threw aside the axe and said: ‘Teach me.’ She performed this action with such grace that he was touched, and to satisfy the gentle supplicant he took her and one of her companions to the Seminary, where they were soon baptized. She made great progress with us, both in the knowledge of the mysteries, as well as in good morals and the science of works [“ouvrages”], in reading, in playing the viol, & in a thousand other little skills. She is only twelve years old and she receives her First Communion at Easter with three of her companions.

Marie’s account calls to mind recent revelations about the systemic abuse (and deaths) of Indigenous children in missionary and residential schools in Canada — dating from the 17th century into the late 20th — as well as an awareness of the broader history of “aggressive assimilation” and the colonization of Indigenous Peoples and territories in Canada. (The United States has its own similar history, still not widely reported.) That the young Indigenous girl in the French nun’s story initiated her own kidnapping should be read with some skepticism. But care must also be taken to acknowledge the agency and adaptability that Indigenous people managed to exercise in their mastery of the cultural practices of their colonizers, even as we chronicle the violence and power imbalances that characterized missionary activities.

Unbroken Chain

Although there are documents and contracts involving several unknown or lost instruments, the five viols traceable to the Hôpital are known, and their varied paths to their current whereabouts illuminate compelling moments in 19th-century early-music revivalism that would otherwise be lost to history.

Today, the five instruments traceable to the Hôpital are:

— Dessus de Viole (Royal Ontario Museum, 913.4.6)

— a seven-string Bertrand bass, dated 1712 (Université de Montréal)

— a seven-string Bertrand bass, dated 1720 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

— a treble or pardessus by Jean Villiaume (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

— a treble by Antoine Cabroly, dated 1734 (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The distinction between the treble and pardessus for the Villiaume instrument is of special interest, as the latter was specifically designed to allow women to play violin repertoire without compromising their modesty, since holding a violin in the traditional way draws an unseemly attention to the shoulder and chest.

Like many bass viols from the period, the necks of both Bertrand basses had been altered, likely prior to their internment in the “caveau,” to reduce the number of strings from seven to four. The fact that both basses emerged from the Hôpital set up for just four strings helps explain the various archival references to each instrument as a “violoncello” and contributes an important detail to our understanding of how the instruments may have been used by 18th-century musicians at the Hôpital.

The earliest known reference to the “caveau” viols, perhaps tellingly, does not mention their miraculous emergence from a vault. The notice, printed in Québec’s Morning Chronicle and Commercial and Shipping Gazette in October 1864, begins, “Ancient Musical Instruments.—We saw, yesterday, at the stores of Messrs. Snaith & Co., St. John street, two violins and violoncello, which are probably the oldest musical instruments in Canada…[T]he violins seem to have been originally used as viols or seven-stringed instruments. Their form, as well as that of the violoncello, is peculiar in the extreme, and highly suggestive of their antiquity.”

LeVasseur’s 1919 article also mentions that three instruments had been sold by the LaRue music store to “a wine Merchant named Snaith, rue Saint-Jean.” We next read about these two trebles and one bass viol in the 1904 Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Hand-Book No. 13, Catalogue of the Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments of All Nations, where they are listed (as items 1343-5) and briefly described. A footnote directs to a brief account of the instruments’ provenance in the “Hospital Generale in Montreal” [sic] in language that repeats key phrases of the short newspaper writeup from 1864. (According to Thomas MacCracken, compiler of the Viola da Gamba Society of America’s Online Database of Historical Viols, old catalog cards for the two treble instruments in the Met’s files read “purchased from Mr. Snaith.”)

Thus we have, amazingly, a nearly complete chain of custody for the three viols now in the Met: imported from France to the Hôpital-Général de Québec; interred in the “caveau” during the Siege of Québec in 1759; “discovered” c.1860 during work on the masonry of the Hôpital; transferred to the music store of Eliseppe LaRue, in Québec, and subsequently sold to Mssr. Snaith, wine merchant, sometime during the early 1860s; sold c.1899 to Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown; and, finally, donated as part of the Crosby Brown Collection to the Met Museum prior to 1904.

A Bridge Across Land and Time

It’s worth mentioning that early-music revivalism, whenever and wherever it has occurred, has necessarily been preceded by an interest in — and accumulation of — musical instruments.

The Crosby Brown Collection forms the core of the Met’s musical instrument collection and is one of several that have been essential to early-music revivalism in North America. The Crosby Brown Collection, assembled by Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown (1842–1918) in New York starting in 1884, as well as the Belle Skinner Collection, assembled during the early 20th century in Holyoke, Mass. by Ruth Isabel (“Belle”) Skinner (1866–1928), represent important contributions to early-music revivalism by American women who understood the potential of musical instruments to bridge historical and geographical distance.

The small viol given by the Mother Superior to the visually-impaired violinist and exchanged by Québecois luthier Joseph Lyonnais (as recounted by LeVasseur) ended up in the collection of musical instrument builder and dealer Richard Sugden Williams (1834-1906). R.S. Williams got his start, age 11, as an apprentice to William Townsend, of Toronto, a melodeon maker originally from Massachusetts who had relocated to Canada to build and sell reed organs, an instrument that was transforming the North American musical landscape during the 1830s and 40s. In addition to the small French treble viol now in the Royal Ontario Museum, Williams brought to Canada numerous viols and violins by the most sought-after European masters.

That leaves only the 1712 Bertrand bass viol, which has had the most interesting (and perhaps tortuous) journey since its disinterment from the Hôpital, including a couple dramatic restorations, a trip to Philadelphia in 1876 for the American Centennial Exhibition, a role in the instrument collection of the Université de Montréal, and longtime service in performances by viol player Margaret Little.

Returning to LeVasseur’s 1919 article in La Musique, quoted at the start of this article, we read:

In 1878, Mr. Sheppard sent the bass viol to the great Philadelphia Exhibition, where it appeared in the exhibition catalog and won first prize as the oldest musical instrument on the continent.

This may be the moment to acknowledge the limitations of narratives like this, a fifth-hand account of events that had (purportedly) occurred more than half a century in the past. LeVasseur’s “souvenirs” provide an irreplaceable source of historical information, but, as with all oral histories (even when later printed), some care must be taken.

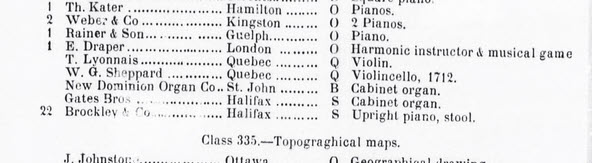

For example, only five instruments are traceable to the Hôpital in the 19th century — there were probably not a “dozen” viols in the vault (whether or not there were additional, unusable fragments, as suggested by LeVasseur). It’s easy to imagine how a bit of embellishment might creep into a story retold for decades. Certainly, the Centennial Exhibition occurred in 1876, not 1878, and archival materials associated with the Exhibition, while they do list the presence in Philadelphia of W.G. Sheppard and “T.” Lyonnais (a misprint of Joseph Lyonnais’ first initial), no prizes were awarded for “the oldest musical instrument on the continent.” The published report on the awards for “group XXV: Instruments of Precisions, Research, Experiment, and Illustration, Including Telegraphy and Music” specifies that “[a]n exhibitor, who is not the manufacturer or producer of the article exhibited, shall not be entitled to an award.” Is it possible that LeVasseur confused in his memory the reference to the “caveau” viols from 1864, which asserted that the viols were “probably the oldest musical instruments in Canada”?

Records associated with the 1876 Exhibition show that Joseph Lyonnais and William Sheppard made their way from Québec to Philadelphia and back with display items in tow, including a violin by Lyonnais (which does not appear to have won a prize), the “violoncello” dated 1712 (which sported only four strings due to an 18th-century “conversion”), and a “Bible (1555).” Did Sheppard bring “antiquarian” items to Philadelphia to communicate Québec’s — and, by extension, Canada’s — historical links to European high culture? Note that the Quebecers’ trip occurred less than a decade after confederation: the formation of the Dominion of Canada via the U.K.’s British North America Act of 1867.

National and cultural identities are often expressed in relation to historical claims, to the idea that a given identity has weight and substance grounded in history. One wonders whether the venerable Hôpital (an architectural model of which was proudly displayed in the “Canada” area of the Exhibition), the ancient Bible, and the “violoncello” were all understood to communicate the ancient presence of European culture in Quebec as an essential precursor to the newly emergent identities resulting from Confederation. Or perhaps Sheppard just thought they were fascinating and worth sharing. The Exhibition judges, which included Secretary of the Smithsonian Joseph Henry, do not mention Sheppard’s artifacts in the Exhibition reports.

National and cultural identities are often expressed in relation to historical claims, to the idea that a given identity has weight and substance grounded in history

LeVasseur tells us that a couple of decades after the return of the 1712 Bertrand bass viol to Québec, Roch Lyonnais succeeded in reassembling the instrument yet again (“In 1917…[Roch] Lyonnais gave it a new lease of life. Its owner, last we heard, was asking $500.00”). By the 1960s, the viol was owned by one Jacques Simard, a Québecois oboist who would eventually donate the instrument, by then in pieces, to the Université de Montréal. Luthier Philipe Davis would restore the viol to playing condition by 1983. Played for decades by Canadian viol virtuosa Margaret Little, the 1712 Bertrand is now listed among the instruments available to students in the Atelier de musique baroque of the Université de Montréal.

So, what can we learn from this uniquely detailed record of the journey of five viols across three centuries of North American history?

Imported to support the activities of a powerful and well-funded religious institution at the center of the French colonial project, the instruments would be forgotten amid the chaos of war and French and British wrangling over the spoils of North America. When they again emerged just before the 1867 Confederation, their connection to French high culture appears to have made them valuable as collectible antiques, as tools of a lost musical tradition, and, perhaps, as symbols of a nascent Canadian identity formed in the encounter of “Europe” with the lands and peoples of the New World.

We can also see how material heritage was moving away from local and provincial spaces toward the concentrations of capital (financial and cultural) represented by museums like the Met or the Royal Ontario Museum. LeVasseur lamented in 1919 that, “all our historical relics are constantly running off to the four cardinal points of the continent, instead of being brought together in [a museum] in [Québec]…When the foreigner doesn’t make them his own, they’re left to be discarded in ignorance, or burned to the ground.”

But revivalism entails reimagining our relationships to artifacts like instruments, as well as the inevitable transformation of “historical” practices and ideas. Are instruments static relics of a past age, or are they alive, animated not only by being played but by the constant shifts in how people of the present understand themselves in relation to the past? The various journeys of the five known “caveau” viols, awakened from a century-long slumber in a damp vault, offer glimpses of the dynamics of revivalism that are at once familiar and, at the same time, specific to the people, places, and material culture of Québec.

Loren Ludwig is a viol player and music researcher based in Baltimore. He holds a B.Mus. from Oberlin Conservatory and a Ph.D. in musicology from the University of Virginia. He blogs at lorenludwig.com. A frequent EMA contributor, he last wrote about a mystery instrument from old New England.