by Steven Silverman

Published January 19, 2026

Louis Couperin: The Complete Works. Jean Rondeau, harpsichord, organ, and artistic direction. 10 CDs + DVD. Erato/Warner Classics, B0FLGGQWK2

Jean Rondeau’s 10-CD compilation of all the known works of Louis Couperin (1626-1661) is a cornucopia of delights. His harpsichord playing is off-the-charts terrific, as are his collaborations with esteemed instrumentalists and vocalists. Rondeau’s traversal of the complete known organ works is an added plus, as is the inclusion of keyboard and instrumental music by a dozen of Louis Couperin’s contemporaries. In all, some 300 pieces of music.

Louis Couperin was a scion of the Couperin musical dynasty. He was plucked from rural obscurity by the royal harpsichord master Jacques Champion de Chambonnières, who evidently knew genius when he encountered it. With Chambonnières’ patronage, Louis Couperin became organist at the prestigious Church of St. Gervais in Paris — a position the Couperin family retained for nearly two centuries — and also obtained appointments to the royal court. Couperin died at 35, having lived only 11 years after coming to Paris (and thus never encountered his nephew François, “le Grand” Couperin, even as an infant).

None of Louis Couperin’s music was published in his lifetime, nor do we know of any existing manuscripts. There are several tranches of roughly contemporaneous copies of his music, with a good portion (including essentially all his music for organ) going undiscovered until the mid-20th century. Eventual publication was delayed until the 1990s. In these sources, the pieces are not compiled into larger units but rather are grouped by common key. Performers are thus at liberty to assemble pieces into suites by taste, commonly compiling suites from pieces in the same key, as Jean Rondeau does here — with a certain amount of duplication, for example, including the “Tombeau de Mr. de Blancrocher” in three different F-Major suites. The odd piece out is a masterwork, the mournful Pavane in the then-unprecedented key of F-sharp minor, which Rondeau plays as the final piece of a Suite in A (on Disc IX). The set also includes a separate performance of the Pavane on organ and in effective (and affecting) transcription for viol consort.

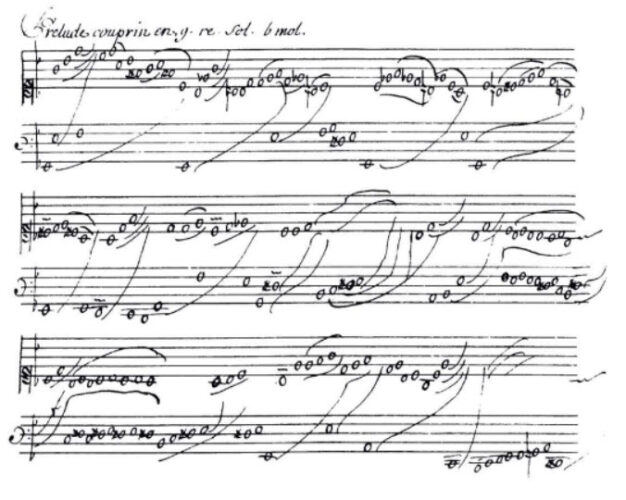

Louis Couperin is most celebrated for largely creating both the keyboard unmeasured prelude, and the means of notating it — as unbarred, unmetered, unsynchronized whole notes under swirling slur signs. The world of the lute improvisation thus not only came into the province of the keyboard, but so did a means of memorializing it. Couperin is also credited with most fully integrating the broken chord stile brisée from the lute to the keyboard, and with being one of the first to specify organ registrations.

In some “complete oeuvre” compilations you find perfunctory renditions of some of the repertoire in the interest of completeness. That is emphatically not the case with the harpsichord music recorded here, comprising the great bulk of this box set. Rondeau plays each piece with total identification. The playing is both technically impeccable — passage work just so, ornaments crackling and executed at different speeds so that trills and mordents vary tellingly by context, never lapsing into uniformity — and is unfailingly alive and expressive.

Rondeau’s vaunted skill in improvisation serves him admirably. He typically plays a section straight the first time through (even removing some notated ornamentation), and then adds exuberantly elaborate, florid ornamentation on each repeat. The effect is of a joyous, seemingly spontaneous discovery of the range of possibilities inherent in the basic material. Rondeau is also alert to the expressive possibilities of the many unusual harmonies (e.g. augmented chords, chromatic modulations, intervals that are “bad” in the particular temperament) with which this music abounds, not letting these moments go unremarked. His staggering of the hands is unobtrusive and nicely preserves the melodic lines — for example the F Major Allemande (Disc III) and D minor Galliarde (Disc VII).

He handles the broken chord stile brisée passages with great skill, again varying pacing by context and never falling into mere monkey-see monkey-do imitation of the two hands. A notable instance is the fine frenzy he gets in the broken chord section of the “Blancrocher” Tombeau (in all three of its versions). And when he does play block chords, as in “La Piemontoise” from the A minor suite, he goes to town with irresistible alacrity. Likewise, he creates great swirls of sound with rolled chords, as with the oceanically rolled chords of the refrain of the F Major Chaconne (Disc III). Rondeau’s continuo playing in the viol consort pieces and transcriptions is likewise first rate — well-considered, unobtrusive realizations that are invariably value added.

Very occasionally, I thought we were hearing a bit too many trees at the expense of the forest. The great D minor unmeasured prelude (Disc I) has a big narrative arc that I missed in this more attenuated, detail-oriented reading. Likewise, there is a dance element (gavotte or courante) in the measured middle section of this piece that didn’t come through in his reading. And a few of the allemandes seemed on the slow side, so that when played with heavily ornamented repeats, some of the dance feeling was lost. These are minor exceptions, however. In most cases, Rondeau preserves the dance element even when ornamenting profusely.

I didn’t sense quite this same degree of affinity for the organ music. An instance is the “Fantasy Duretez” (or harshness). One of the recently discovered organ works, this fantasy is notable (as its title indicates) for astringent harmonies, unusual dissonances, and chromatic oscillations. Rondeau performs it on both organ (as originally written) and in his own version on harpsichord. The unusual effects come through noticeably more markedly in the harpsichord version, even though many of the effects result from harmonic changes under tied notes, which should be easier to project on the organ since the sound does not decay. Likewise, I much preferred his harpsichord version of the F-sharp minor Pavane over his version on the organ.

Here it should be noted that there is a dispute over the authorship of the organ music, since its style differs noticeably from the harpsichord pieces. Authorship of some of the organ music is thus sometimes attributed to one of the Couperin brothers (including Charles, father of François “le Grand”) or, as the recording booklet postulates, to a collaboration among the brothers. In any case, some of the keyboardist Rondeau’s seeming reticence in the organ repertoire may reflect the different nature of the organ music vis-a-vis the harpsichord repertoire.

In all, this recording is a must-have for those who love or desire acquaintance with Louis Couperin’s music, and for aficionados of 17th-century French keyboard style generally. Highly, highly recommended!

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York City and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 26th season. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Beethoven’s cello sonatas on period instruments.