by Natalya Weinstein Miller

Published February 13, 2026

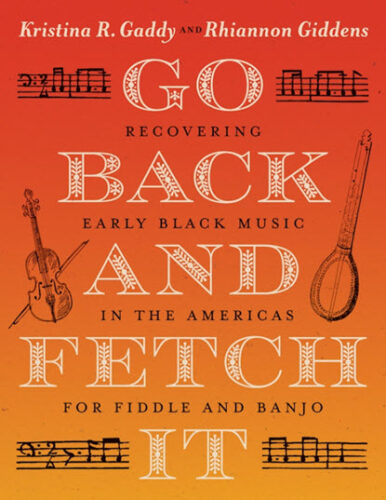

Go Back and Fetch It: Recovering Early Black Music in the Americas for Fiddle and Banjo by Kristina R. Gaddy and Rhiannon Giddens. University of North Carolina Press, 2025, 120 pages.

Two of the leading scholars in the modern study of the origins, structure, and early repertoire of the banjo, Kristina R. Gaddy and Rhiannon Giddens, have teamed up for Go Back and Fetch It: Recovering Early Black Music in the Americas for Fiddle and Banjo, an in-depth examination of early banjo and fiddle music played by free and enslaved Blacks in the Americas prior to the 1860s.

A fiddler and award-winning historian, Gaddy is perhaps best known for her 2022 groundbreaking book Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History. Giddens has become a superstar performer and creator across many genres, from folk to opera, winning Pulitzer, MacArthur, and Grammy awards along the way.

In Go Back and Fetch It, their sources date to as early as the 1680s in Jamaica and come from the Caribbean islands as well as the United States. The authors explain that the subject material was scant and difficult to find because music played by people of African descent was not widely notated or transcribed prior to the late 1800s. In the introduction, Gaddy and Giddens highlight the significance of this collection — the first of its kind — while underscoring the many challenges and limitations of the project.

The 1867 compilation Slave Songs of the United States was the first collection of Black music published in America. Before that point, Black music had not been considered worthy of documentation and publication, a result of racism, prejudice, and slavery. How different things might have been, the authors muse: “Imagine a past where the dynamic sound of different African cultures meeting each other and European cultures in the Americas was made part of the historical record. Where people with power cared about African-derived musical forms and wrote down songs, asked people what lyrics meant, and saved instruments born of the African diaspora.” While this wasn’t the case for the majority of Black music, Gaddy and Giddens are adding their interpretations to the sources we do have and sharing them with the broader public.

Building on a number of references from Gaddy’s Well of Souls as well as contributing multiple new sources, the authors focus on the musical and historical elements of 19 different musical selections with provenances ranging from Suriname to New York.

They emphasize the close ties of Black music to dancing as well as religious practices. The music was usually played on a percussion instrument, the banjo or a banjo predecessor, the fiddle, or sometimes with voice and singing. Call-and-response work songs and participatory songs were an important component. Gaddy and Giddens also explore the process of creolization in early American music, with the tunes and melodies going back and forth between musicians of African descent and musicians of European descent. The music did not stay exclusively in one domain and was thus influenced by a variety of sources.

The biggest challenge the authors faced was the many limitations to analyzing the existing musical records. The songs were primarily documented by people of European descent and were often written down as a side note. Only three of the pieces were actually notated by Black musicians — and those were for a white audience — so there is inherent bias in how they were documented. Also, standard musical notation doesn’t allow for complex tonality and rhythms, which was subject to the listeners’ interpretations of what they were hearing. The rhythmic patterns may not have been familiar to the European transcribers, so they may not have known how to write them down. Despite this, these transcriptions are valuable as the only existing record of these melodies and rhythms.

This meticulously researched book includes an exhaustive bibliography with over 100 sources, with hundreds of notes within the text for easy connection to the sources. Each of the 13 chapters contains one to three tunes or songs, with a thorough description of each piece, often an image of the original notation, a transcription in modern music notation, and banjo tablature. While this seems geared toward musicians, and banjo players specifically, anyone interested in early American banjo and fiddle music, as well as in the African origins of the music played on those instruments, will be intrigued by the material.

One missing component that could have helped in interpreting the selections is sound recordings. For those readers who do not read sheet music or tablature, and even for those who do, a short audio recording of each tune or song would be a dynamic way to bring the music to life. Such an accompanying resource is not a simple undertaking, but could be a future companion project to the book, perhaps via a website or SoundCloud link.

Go Back and Fetch It is a monumental work and should be celebrated for its in-depth research, thoughtful critiques, nuanced reflections, and practical applications. This contribution to the historical record is extremely significant, and hopefully more sources by Black musicians will continue to be uncovered. Any aficionado of early American music will be richly rewarded for their time spent with this compelling project.

Natalya Zoe Weinstein Miller is an instructor of music at Warren Wilson College in Swannanoa, N.C. She holds an MA from Appalachian State University, with a research focus on the diverse origins of bluegrass fiddle music. She also performs in a band called Zoe & Cloyd, with her husband, John Cloyd Miller.