‘If we hadn’t gone to the opera, you wouldn’t be reading this. Attention seeking? Damn straight.’

On November 30, 2023, I participated in Extinction Rebellion’s protest for climate justice at the Metropolitan Opera, a demonstration that interrupted opening night of Wagner’s Tannhäuser for 22 minutes. I planned and organized the action, knowing that the press would be there in full force. A New York Times critic, to cite one example, spent the first two-thirds of his review discussing the protest. He also shared videos and even added a link to Extinction Rebellion’s website. Addressing audience members who were angry at the disruption, the critic asked, “Did they consider that Tannhäuser comes from the most politically active time in Wagner’s life?”

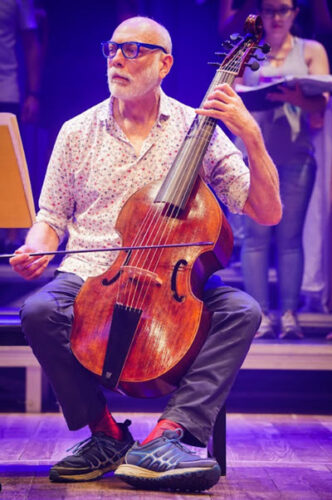

As a viola da gamba player, Baroque cellist, and teacher, I’ve been asked to justify disrupting a musical performance.

For as long as I can remember, non-violent acts of civil disobedience — acts that may violate the law — have been presented to me as effective tactics for social change and social justice. Jesus overturning the tables of the money changers, Bostonian patriots destroying a shipment of tea, Thoreau refusing to pay his taxes, Gandhi making salt, Rosa Parks refusing to sit at the back of the bus, draft resisters fleeing the U.S. to escape complicity in an immoral war — all were presented as principled, proportional, and praiseworthy. The symbolism of Thoreau’s 1846 refusal to pay a $1.50 poll tax as a protest against the evils of slavery should be obvious.

Likewise, anyone who does not yet understand Extinction Rebellion’s action at the Metropolitan Opera as justified needs to be brought up to speed.

The scientific consensus is that our planet is experiencing a sixth mass extinction event (the fifth mass extinction wiped out the dinosaurs). Wildlife populations are plummeting at an accelerating rate, the oceans are rising, storms are more violent, droughts more severe, and conditions that cause catastrophic losses in biodiversity are also causing humans to lose their homes and their lives. In the first two decades of this century, heat-related deaths of adults over 65 in just the U.S. have increased by 88 percent. (I applaud an EMAg article from May 2023, “Community & Climate Change & Early Music,” that discusses facets of global heating.)

Some 50 million people have already been displaced by the rapid change in climate. By 2050 that number may reach a billion, many of them in the “Global South.” People who lose their homes and livelihoods to climate change flee toward Europe or the U.S. by crossing the Mediterranean or the Rio Grande. If they don’t die trying, they face hardship and bigotry when they arrive in wealthy societies that are themselves stressed by the demands to accommodate these climate refugees.

That these environmental disasters are caused by human activity is not a matter of debate. The scale of these problems means that the crisis cannot be effectively addressed without the participation of the world’s most powerful governments — and they have utterly failed to respond. This comes despite years of scientists’ and citizens’ good-faith efforts to work within the system to influence governments by voting, petitioning, writing, and speaking out about the crisis.

Those with the power to change are often minimally affected, which leads to complacency, even among those who acknowledge the scientific consensus. This is the moderate stance that Martin Luther King, Jr. called one of the greatest stumbling blocks against the stride toward freedom. It’s an attitude of enjoying order (and short-term profits) more than pursuing justice. To shake our friends’ complacency was our goal in disrupting the Met Opera.

People ask us why we go to opera houses and museums and sporting events. It’s because when we’re arrested protesting inside Congress’ Rayburn House Office Building in D.C., or arrested for blocking construction of Project Pipes, it gets little attention. If we hadn’t stopped the opera, you wouldn’t be reading this. Attention seeking? Damn straight. Does this look crazy? Please show us where anyone is responding to our climate crisis in a sane way.

Extinction Rebellion is asking its own members to disrupt what we love: artists protesting at museums, athletes interrupting sporting events, musicians interrupting performances.

How would I feel if activists were to disrupt my own concerts? First, I have already disrupted my musical career voluntarily. I have turned down substantial work to give my time to activism for climate justice. Second, if you can disrupt my performances in a way that’s ethical and strategically effective in the pursuit of justice, then bring it on.

If, after all that, anyone is still upset about a 22-minute delay of a theatrical performance by shouting which endangered no one (except for one protester who was violently accosted by other audience members), all I can tell you is: You ain’t seen nothing yet.

John Mark Rozendaal is a Baroque cellist and viola da gamba player based in New York. He has recorded for Cedille Records and performs with Trio Settecento, LeStrange Viols, and Brandywine Baroque.

A reader responds in a Letter to the Editor: Climate Crisis Showmanship

See also: Donna Lee Davidson’s article on Dr. Lucy Jones, ‘The Earthquake Lady and Her Viol: Sounding the Climate Alarm’