Julia Bengtsson has found her footing as a dancer, choreographer, scholar, filmmaker, and unstoppable entrepreneur

‘Historical dance, as a field, is 20 years behind the early-music world’

This article was first published as the cover story in the May, 2025 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

There’s a photograph of Julia Bengtsson in a sleek black leotard, her arms and legs bare. She is standing on one leg, on pointe, the other leg raised high behind her. It’s a classical ballet pose that you’ll never see in 18th-century Baroque dance, which calls for long, full skirts draped over wide-hip panniers and soft slippers or low-heeled shoes.

The distinct techniques of each era make different demands on the performer. But the ambitious 32-year-old dancer-choreographer is accomplished in both, as well as in contemporary dance. For that, she dances barefoot.

Bengtsson follows all those Terpsichorean muses, but the scholarly and historical aspect of Baroque dance appeals to her intellectually. She loves nothing more than to dive into an 18th-century treatise to study hundreds of pages of notations and the musings of dance masters. Her favorite, Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, by Gottfried Taubert, is 1,231 pages in the original German and close to 900 pages in English. She’s read the entire treatise — not in one sitting, she admits — and enjoys some of its more informal sections, such as when Taubert cautions readers not to take classes from the local baker.

She also loves the range of Baroque dance, from the small beaten jumps of the gavotte to the strong, stately tempo of the sarabande. “Every Baroque dance has its own personality,” she says. “There is a common misperception that it’s restrained, but that’s not always true. In Baroque dance, you don’t have to shout, you can whisper.”

Since 2018, the Swedish-born Bengtsson has been with the New York Baroque Dance Company. The ensemble was founded in 1976 by Ann Jacoby and Catherine Turocy, the latter long considered the queen of Baroque dance in the United States. Bengtsson has performed several projects with them including Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas, and has given lectures and presentations with the company throughout the U.S.

Turocy founded the company in an era when no one in America was performing Baroque dance. It was an isolated academic field and remains highly specialized. But it’s where Bengtsson thrives. In 2023, Turocy named her protégée as director of the company’s New Baroque Initiative, which encourages the blending of Baroque dance technique with the more expansive qualities of contemporary dance — a style Bengtsson is becoming known for internationally.

She admits to being obsessed by dance. She often works 10 to 13 hours a day rehearsing, choreographing, or performing. According to violinist Julie Andrijeski, “she is unstoppable. She has the most positive energy I have seen in anyone. It’s a joy to work with her.”

Take the solo that Bengtsson choreographed to Bach’s Cello Suite No. 5. She first performed it at Carnegie’s Weill Recital Hall in New York, in 2020, celebrating the 300th anniversary of the suites. The concert was the brainchild of cellist Stephanie Winters, who assigned each of the six suites to a different cellist. Three of them featured progressive interpretations with song, trombone, even a little juggling. For the 20-minute Suite No. 5, Winters envisioned a dancer illustrating the story of Bach’s wife Anna Magdalena. She felt Bengtsson could perfectly embody Anna Magdalena in her various roles: a young professional musician in her own right, Bach’s copyist, and mother of 13 of his 20 children.

“Julia is a talented dancer,” says Winters. “She is also very professional, very committed, and has a great work ethic. You need that drive to take something from an idea to reality at a high level.”

At the outset, however, Bengtsson had some concerns: “Twenty minutes is a long solo for most dancers, and I didn’t want people to get bored,” she says. “That’s my biggest pet peeve.” So she created a strong narrative arc for the piece.

Dancing barefoot throughout, accompanied by Winters on cello, she follows the suite’s structure which starts with a prelude, then moves to an allemande, courante, sarabande, gavottes, and a gigue — all highly stylized 18th-century dance forms. “It’s very important to consider the time and place where Bach lived, so I consulted Taubert, a dancing master who was Bach’s contemporary and worked in Leipzig at the same time.” While she would have enjoyed a trip to Leipzig, she did her research at home, drawing from online resources such as the Library of Congress and the French National Library’s Gallica. (She owns one of the rare copies of Taubert’s Rechtschaffener Tantzmeister, a prized gift from Cornell historian Rebecca Harris-Warrick, whose book Dance and Drama in French Baroque Opera is essential reading.)

Bengtsson begins the prelude in Baroque style — small steps, an erect stance — and gradually moves into contemporary technique, which includes a highly expressive torso. For the allemande, she stays seated while moving her arms in the style of contemporary dance. For the courante, in a completely Baroque style, she referred to the Taubert treatise, although she admits to taking liberties with the prescribed arm movements in order to be more expressive. Baroque dance requires acute attention to detail, something that comes naturally to her. She created contemporary choreography for the sarabande, with high extensions and falls to the floor, before dialing back to Baroque again for the gigue. She also played with the cadence of Baroque dance and extended the shape and size of some steps. She amplified the tombé (“fall”) by “falling” or dropping her entire body to the floor, a movement drawn from contemporary dance. If Baroque called for a small leap, she expanded it to a grand jété.

Bengtsson was coached in the Bach solo by Turocy and Andrijeski, who is artistic director of the Atlanta Baroque Orchestra and was part of the project from the beginning. (The Baroque dance world is small; it seems everyone knows everyone else.) Andrijeski is also head of the Historical Performance Program at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, where she teaches Baroque violin and Baroque dance to musicians. For the Bach suite she helped Bengtsson better understand connections between music and movement.

“Julia came in with wonderful ideas,” Andrijeski recalls. “She is so good at both contemporary and Baroque dance, we gave her carte blanche in what she wanted to do and how to present it. She heard the different colors and emotions” in the music. “I tried to go a little deeper with her and have her show it in her eyes.”

Unlike many dancers, Bengtsson can read music (self-taught), so she understands the timing, tone, and rhythm of a work and can follow the score. When analyzing the suite with Andrijeski, she learned where Bach follows musical conventions and where he doesn’t. “Because Bach knew the rules so well, he could break them or manipulate them. He took daring leaps, challenging convention,” Andrijeski says. Bengtsson wanted to do the same in dance.

Since the premiere, she has performed the Bach solo on several continents and with a variety of cellists, including at Early Music America’s 2022 Emerging Artist Showcase, part of the Berkeley Early Music Festival and Exhibition:

The solo illustrates beautifully the neo-baroque style for which she is becoming known, but it also shines a light on the fact that many period-instrument Baroque orchestras, if they program dance in their concerts or opera productions, are turning more and more to neo-baroque or pure contemporary dance. Even hip-hop. William Christie’s trend-setting Les Arts Florissants painstakingly recreates the sounds of Baroque opera from the latest musical scholarship, but typically takes a creative leap in its collaborators. Les Arts Flo’s production of Purcell’s The Fairy Queen, seen at New York’s Lincoln Center in 2023 and on video, featured dance by Mourad Merzouki, a French Algerian hip-hop choreographer and stage director, and it was performed in street clothes by members of his Compagnie Käfig.

Not every Baroque orchestra can afford to do productions this wild and unconventional. But on a smaller scale, many U.S. ensembles likewise prefer to partner with contemporary dance companies. This is for a variety of reasons, Bengtsson believes: There are far more contemporary dancers than trained Baroque dancers; the venues where Baroque orchestras frequently perform — churches, historical mansions — often have a space or flooring that’s not appropriate for dance; and it’s expensive to produce live music with dance, especially if it involves flying an ensemble like the New York Baroque Dance Company across the country. There are “absolutely brilliant” Baroque choreographers today, Bengtsson says, but they have difficulty reaching music presenters and raising funds. (For her part, in interviews, Turocy has said she sees no cognitive dissonance between historically informed music-making and modernized aspects: “I can recognize tropes in the music, so when I’m putting it into a modern [dance] style, it’s just that it’s being translated to today’s feelings.”)

Bengtsson believes that historical dance, as a field, is 20 years behind the early-music world. “Historically informed performance practices have not been recognized as seriously as classical music traditions,” she says. “Many people do not have a clear picture of what’s possible to achieve through research by [dance] artists.” Perhaps because of this music-dance dissonance, she finds musicians sometimes resist changing the tempo or phrasing in a piece of music. “There might be situations where the dance dictates what is possible in the music,” she says. She’s not afraid to communicate that to musicians, some of whom are not receptive. More typically, musicians remark that after rehearsing and performing with dancers, even in a familiar piece of music, they can glean new insights and approaches.

The ‘Excitement’ of Early Dance

Bengtsson was born in Gothenburg, the second-largest city in Sweden, and she remembers her first performance. It was on December 13, Santa Lucia Day, when she was five years old. On that auspicious holiday on the Swedish calendar, children perform for their families and community, dressed in white and singing traditional songs. “After that, my parents tell me, I couldn’t stop talking about wanting to perform,” she says, but they were not interested in Bengtsson’s pursuing a career in the arts. Before she retired, her mother was a scientist in pharmaceuticals; her father worked in computer systems. Still a toddler, her parents tell her, she played along with her toy drum to a Turandot CD. Trips to the opera house in Gothenburg soon followed. She was forever hooked.

Her parents arranged for her to study ballet locally. Then, at 16, she moved to Stockholm to attend the Royal Swedish Ballet School, where she studied for three years. Like ballet students worldwide, she learned almost nothing about Baroque dance or the history of the technique she now works tirelessly to master. Music teachers include music theory in their instruction, but few dance teachers delve into dance history or theory. To take one telling example, respected scholar and post-modern choreographer Wendy Perron, former editor of Dance Magazine, is the only faculty member at Juilliard listed as teaching Dance History. When I contacted her for some general background for this article, Perron replied in an email: “Sorry I have no idea about Baroque dance.”

It’s lamentable but perhaps not surprising. University dance programs are designed to prepare dancers for professional dance careers. The competition is fierce. A dancer’s working life is short — much shorter than that of a musician’s, who may not peak until later in life and can perform professionally for many decades — and few dancers are interested in dedicating their youthful athletic years to a smaller movement range. Bengtsson bemoans the fact that today’s dancers can easily execute multiple pirouettes but don’t appreciate “the excitement” of historical dance.

She discovered this excitement early on. Curious and adventurous, as a ballet student in Stockholm she responded to a call for a non-ballet school production, what she describes as a Henry Purcell pastiche. She auditioned and made the cut. “It was fun. It was also eye-opening because I couldn’t do it! The coordination and momentum were so different from ballet.” She did well enough, however, that the choreographer, Karin Modigh — the only professional Baroque dancer in Sweden at the time — introduced her to Turocy.

That connection changed the trajectory of not only of Bengtsson’s career, but of her life. She attended workshops with Turocy in New York. During the pandemic lockdown, the two of them had time to work closely together, which is when she mastered 18th-century dance notation. She can now read it fluently, just as a musician can sight-read an elaborate score.

“She is very thirsty for knowledge, like a sponge,” Turocy says. “She is also very social, an entrepreneur, and is able to network and collaborate, not only from an artistic point of view, but as a way of being part of the community.” This is not the usual combination for a dancer, Turocy adds, praising Bengtsson’s affinity for the administrative chores of networking, creating budgets, grant writing, and audience development.

Bengtsson didn’t attend university, but at 19 received a scholarship with the Joffrey Ballet School in New York. She loved Manhattan and voraciously consumed everything it offered — dance, music, museums, film festivals, street art. Her first professional contract was with the Connecticut Ballet, where she performed The Nutcracker among other works. She has remained in the U.S. on artist and work visas and is now in the process of getting a green card.

In 2013, she met her now-husband Peter Thompson. A clarinetist and Eastman School of Music graduate, he left music performance and earned a doctorate in math, but it’s music that connects them, and Bengtsson often seeks his advice. He’s adept in languages, too: After meeting Bengtsson, he quickly learned Swedish. At home, they are disciplined enough to alternate languages: one week English, one week Swedish.

When she got pregnant, she was frequently bedridden with a rare condition known as hyperemesis gravidarum, a severe type of morning sickness, but kept dancing and choreographing as much as she could. “I don’t know who I am if I’m not moving,” she says. After their son Jesper was born in April 2023, they moved from Manhattan to a larger apartment in White Plains, a five-minute jog from the nearest dance studio. Bengtsson knows the timing well: She jogs there most mornings to choreograph and rehearse.

She’s also a pro on Instagram, posting photos and short videos of her performances, a brilliant way to communicate her excitement to the wider world. (Squeezed among the dance images is a photo of her son’s first footprints in clay, neatly framed. “Life will never be the same!” she posted.)

‘I don’t know who I am if I’m not moving’

Jesper is probably the most traveled two-year-old in White Plains. Whenever she is away from home for more than four nights, Bengtsson takes him along. When she works in Europe, her mother and sisters are on hand for babysitting. Less than four months post-partum, she and Jesper flew to Sweden, where she danced in Turocy’s Les Caractères de la Danse.

In 2023, Bengtsson got a commission from Confidencen Theater in Stockholm to choreograph and stage-direct an opera pastiche titled Baroque Catwalk. Thompson went along and took care of Jesper while she was working. “My schedule was supposed to be eight hours a day,” she recalls, “but our costume designer dropped out. I was working 12 or 13 hours a day. That was difficult.”

In the spring of 2024, she choreographed a portion of Jean-Joseph Mouret’s comic opera Les Fêtes de Thalie for the New York Baroque Dance Company and Opera Lafayette, performed at the Kennedy Center. The project required that she stay in Washington, D.C., for several weeks, a long stretch for a new mom. Thompson drove them there, but when he had to return home, Bengtsson hired babysitters. It’s no surprise that she describes herself as obsessed by her work, but she smiles when talking about watching Jesper move with the music. Baroque music, of course.

Bengtsson has twice choreographed dances to Bach’s Goldberg Variations — like the cello suites, it is music built up from dance rhythms although not originally associated with dancers. In 2018, she created a short film performing her own Goldbergs choreography, accompanied by Chinese pianist Tianqi Du, to illustrate Bach’s counterpoint and musical structures. Six years later, she created a neo-baroque duet for a performance with the Baroque Chamber Orchestra of Colorado, which had commissioned a new orchestration of the Goldbergs for strings and continuo.

“I was acting on intuition in 2018,” she explains, “but today I know more about how Baroque composers structured and shaped the music. Where there is a full stop, or a comma, or a question mark — it’s a conversation. Once I know what the music is saying, I can structure the choreography so that I am saying the same thing.”

Those two Goldberg Variations performances, six years apart, illustrate Bengtsson’s growth as a choreographer, dancer, filmmaker, Baroque dance scholar, and unstoppable entrepreneur.

“Julia knows a lot about music structure because she’s reconstructed sarabandes, gavottes, and minuets from notations,” Turocy says. “A contemporary choreographer with no Baroque training will create one movement over an eight-measure phrase, but in Baroque work every measure has its own beginning and end, so together they create a larger picture at the end of each musical phrase.” She demonstrates with her hands. “Julia uses those smaller units of rhythm and space which lead to the end of a musical sentence.”

Bengtsson enjoys the connection between Baroque dance and music because, unlike in many contemporary dance forms, the movement and music are in constant conversation. It’s no surprise, since many18th-century dance masters accompanied themselves on the violin. She now experiences Bach’s music in color, instead of black and white.

Dance as Political Power

Classical ballet dancers do a daily barre, followed by adagios, turns, and jumps in the center of the room, just to maintain their technique. Bengtsson still takes ballet class, but says that Baroque dance has a much different emphasis. “How I train in Baroque is more a matter of reading manuals and reconstructing dance notations.”

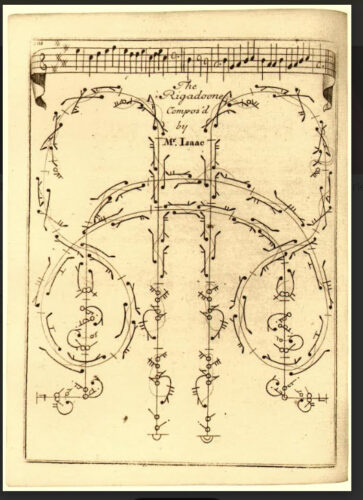

These notations are the lifeblood of Baroque dance today. They enabled dance masters of the time to record in detail the steps of the dances they created. And record they did. There are an estimated 350 notated Baroque dances in existence. Bengtsson has read or consulted dozens of them and likes nothing better than to go down a rabbit hole of historical study.

Classical ballet dancers do a daily barre, but how you ‘train in Baroque is more a matter of reading manuals and dance notation.’

The French names for steps in Baroque dance can still be heard in ballet classes today. The pointed feet, the turnout, all go back to 17th- and 18th-century dance. What is not heard in today’s ballet world are references to the actual dances of the time, for instance the allemande, courante, sarabande and gigue — the standard model of many Baroque instrumental suites.

Dance as a courtly endeavor in France reached a pinnacle during the reign of Louis XIV, a patron of dance who ruled from 1643 to 1715 and shaped the country’s cultural habits forever after. The king was a skilled dancer; his first performance, in 1653, lasted 12 hours before a captive audience of courtiers. (Meanwhile, Bengtsson is worried that a 20-minute solo would bore her audience!)

Louis also used large-scale ballet as a political tool to impress visiting foreign dignitaries. The popularity of dance in his court led to the founding, in 1661, of the first ballet school, the Académie Royale de Danse. In the ancien régime, dance had become a branch of government.

Several dance notation systems were developed in the 1680s, most prominently by court choreographer Pierre Beauchamps. Building upon Beauchamps, Raoul Auger Feuillet’s system, published in 1700 as Chorégraphie, ou l’art de décrire la danse, set the standard. “As a result,” writes Cornell historian Harris-Warrick, “we know more about dance of this era than of most periods before or after.”

In 18th-century France, dance notations were published just like sheet music and sold to the public, so anyone who could read notation could learn new dances. Which is what Bengtsson does now, three centuries later. She describes Chorégraphie as a kind of Rosetta Stone: “He includes what the step is called and how it’s notated. Once you know the name of the step, you can refer back to the different dancing manuals to see how that step was performed at different times and places. When I look back at a particular chapter, maybe a few months later, I see different things.”

Bengtsson creates contemporary works, too, some of which address political issues. Strangers is a modern story-ballet about immigration with music by composer Brian Morales, parts of which were performed by the Connecticut Ballet in 2020. Bengtsson not only did the choreography but also created masks inspired by commedia dell’arte.

Morales was her collaborator, too, on 7 Questions You Should Answer Truthfully, a 25-minute work responding to the wave of populism that was sweeping the world in 2019. It was a follow-up to her 2016 Blank Space, a dance about immigration and political repression in which she drew parallels with the rise of Nazism in the 1930s as documented by Charlotte Salomon, a German-Jewish visual artist and victim of the Holocaust. Bengtsson responded to America’s opioid crisis when she stage-directed and choreographed Orfeo 2018, a modernized version of Monteverdi, set in New York’s Washington Heights neighborhood.

In all, she has created more than 20 productions as well as taught, lectured, and led workshops across the country, mainly about Baroque dance, from Cornell to Stanford. She is frequently involved with two or three projects at a time. Long hours, seven days a week. Her greatest desire is to continue stage-directing operas that include dance. In 2019, she directed Opera Lafayette’s semi-staged production of John Blow’s Venus and Adonis, which included workshops and artist talks about the production.

At 73, Turocy is grooming Bengtsson to be on a leadership team that will include the current associate director, Caroline Copeland. Together they will run the New York Baroque Dance Company when Turocy steps back from her full-time role. She is also guiding Bengtsson’s next goal: studying 19th-century early-ballet technique with Alan Jones in Paris.

One step in that direction is In Honor of our Illustrious Guest: General Lafayette, which premiered in December 2024 in New York. Bengtsson and Jones were commissioned to reconstruct dances that were set to music by Francis Johnson (1792-1844), a Philadelphia-born performer and composer and one of the first known African Americans to publish sheet music. Bengtsson told Johnson’s story through narration and 10 dances, created during a residency with Jones in Paris. (Once again, her husband and baby Jesper went along for the ride. They played in the Luxembourg Gardens while Bengtsson was in the studio.)

For research, Jones directed Bengtsson to consult an 1817 Franco-American treatise, Victor Guillou’s Elements and Principles of the Art of Dancing. It shines a light on Johnson’s forgotten dances, which were commissioned in 1824 for the Marquis de Lafayette’s grand ball in Philadelphia. No one knows if Francis Johnson created them, only that the choreography and music were published together. Bengtsson found it extraordinary that annotations on the spatial paths and dance steps performed at the premiere were noted in Johnson’s musical score. For a scholar like Bengtsson, it was manna from heaven.

When there’s something to be discovered, she will be at the front of the line, finding a way to make old things new again.

They’ll present Illustrious Guest again at the Hillwood Estate in D.C. (June 2025), and in Philadelphia (May 2026) as part of the Soundtrack of Independence festival, celebrating the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Directing this project is historical clarinetist Dominic Giardino.

Giardino knew of Bengtsson’s Baroque specialty but “had no idea she was interested in 19th-century music. It speaks to her curiosity.”

He arranged Johnson’s music from the piano scores for instruments that would be comfortable for dancers to work with, while still being appropriate to American dance bands of the 1820s. “I was pleasantly surprised to see how open Julia was to working with what might be weird or unconventional instruments in the context of dance, such as a keyed bugle or ophicleide.” He values the trust they have in one another.

“If there is work to be done and something to be discovered, she will be at the front of the line, exploring a way to make old things new again,” he continues. “And she is meticulous. When I think of Julia, I think of unbridled ambition. She is a go-getter, and there is no stopping her.”

Gillian Anne Renault’s dance writing has been published in numerous outlets including Ballet News, the Los Angeles Daily News, and ArtsATL.org. She hosted dance interview shows on radio stations such as KUSC and KCRW and was a recipient of an NEA fellowship to attend American Dance Festival’s Dance Criticism program.