by Geoffrey Burgess

Published September 16, 2024

A call to re-evaluate current practices

Throughout history, instrumentalists have been instructed to imitate the human voice. But how did people sing centuries ago? What did their voices, their expression, sound like?

What’s normal or natural today may have once been viewed as quite the opposite. We have been subjected to significant cultural influence, removing us from historical practices and creating a growing divide between vocal and instrumental practices.

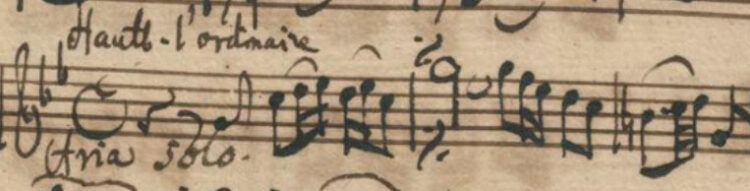

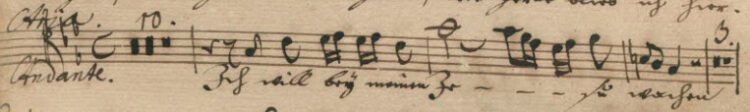

As a historical oboist, if I am going to imitate the human voice when I play an obbligato like “Ich will bei meinem Jesus wachen,” from the St. Matthew Passion, I must do more than simply make a smooth singing line and uniform tone.

I will articulate the phrase according to the text by imitating the play of vowels and consonants in note lengths and releases, and in dynamic nuances. The consonants in the first two words — /ɪç vɪl/ in the International Phonetic Alphabet — tell me to separate the anacrusis from the downbeat. The energy that this gives to the rising fourth matches the enthusiastic resolve expressed in the text.

The next string of words is more liquid with the closed sounds of “m” and “n”and similar vowel sounds (/aɪ̯/ and /ə/). The last “m”slides into the “j” of Jesu.

Here I will execute the rising fifth with a subtle drop in volume that allows the sustained high G on Jesu to bloom. From there the phrase curls down to the verb wachen with its two crisp consonants and light final syllable. By “reciting” the notes in this way, I’ve already created meaning. When the tenor enters, he explicates that meaning through the addition of text:

This is as much about creating space and movement in sound as about the sound itself. As the aria progresses, where resolve and human frailty tug at each other, the oboist and the singer share the same material. Close attention to the text and dialogue can be very satisfying and very moving. Yet somehow, nowadays, this seems difficult to achieve in performance.

Modern circumstances have taken us far from the collaborative nature of early music and the shared goals of singers and instrumentalists. The economics of classical concerts often force us into larger auditoriums where vocalists feel obliged to increase volume, use more vibrato, and diminish or even eliminate consonants, which can render “Ich will bei meinem Jesus wachen” an inarticulate vocalise. Baroque instruments are not designed for maximum volume and are easily covered by singers who are placed at the front of the stage. To stay together, instead of listening and reacting with nuance and inflection, we are obliged to watch a conductor.

This is not a rant against singers, but a call to re-evaluate current practices. Increasingly, singers feel the need to become generalists, and are nudged toward operatic careers that, in all but exceptional cases, require the cultivation of a technique that takes them further from practices suited to early repertoire. Recordings reinforce this when larger-than-life singers are set against an indistinct instrumental background.

Vibrato is another divide separating singers and instrumentalists. If I copy vocal vibrato on the oboe I am ridiculed: I have overstepped the line from imitation to parody. What’s clear is that when vibrato obscures text, limits agility, and reduces expressivity, it fails to be an effective tool for HIP.

Historical instruments can illuminate historical vocal practices. The vox humana stops on a Baroque organ have a tremulant quality, achieved either by an oscillation in the air supply or by two ranks of pipes tuned slightly apart from each other. Does this mean that continuous vibrato was considered an essential hallmark of singing? This mechanical imitation of the voice was one stop of many — a special effect reserved for specific contexts.

Our voices naturally tremble when we are overwhelmed by intense emotions: anger or shock at one extreme, sorrow or fear at the other. These are the emotions Bach represented in “Zerfliesse mein Herze” from the St. John Passion, with sobbing repeated notes and vocal tremolandi. This is one style of musical representation; other emotions have their own techniques.

Baroque music invites us to represent a gamut of emotions, each with its own distinctive voice. This calls for more than a smooth uniform tone, but a tone with space, motion and variety that “speaks” the language it expresses.

Historical oboist Geoffrey Burgess performs internationally, including two decades as a member of the Paris-based Les Arts Florissants. He is the author, with the late Bruce Haynes, of The Oboe and The Pathetick Musician. He teaches at the Eastman School of Music and is editor of American Recorder and The Double Reed.