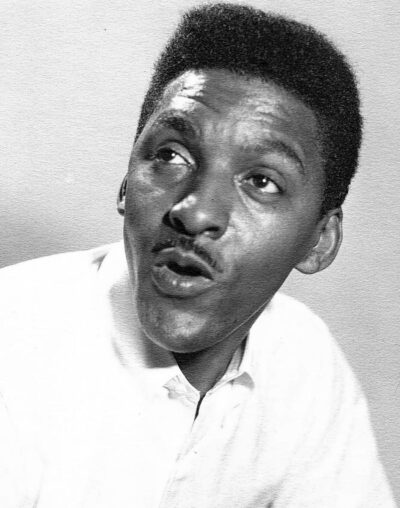

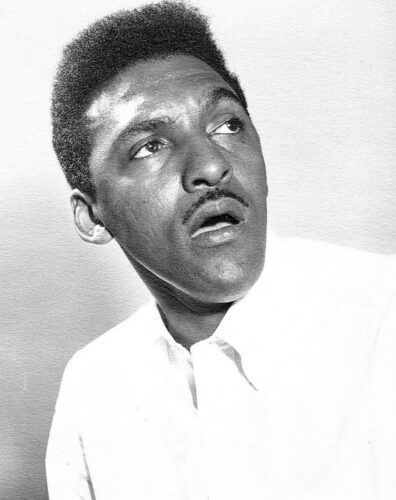

Bayard Rustin, a luminary in the Civil Rights movement, performed and recorded early music in the 1950s and 1960s and collected historical instruments at the dawn of New York’s early-music revival.

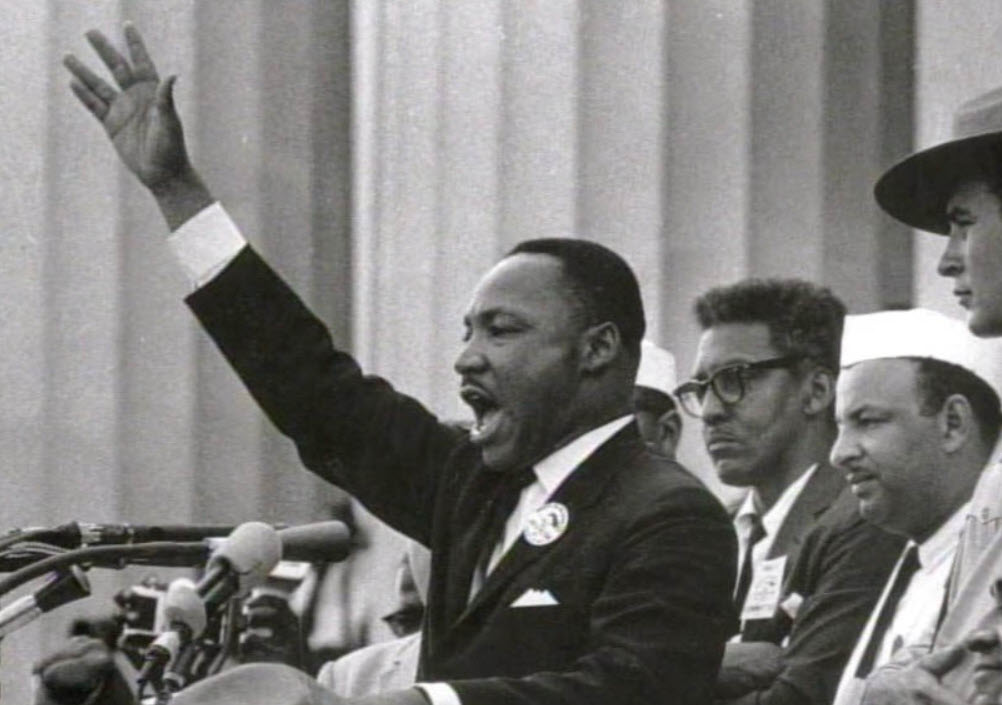

Called the Black Socrates of the Civil Rights movement, Bayard Rustin taught Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. tactics of non-violent protest. Rustin organized and participated in the Freedom Rides, an effort to desegregate interstate bus travel in the Deep South that was met with violence. He organized the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where he spoke and where King delivered the “I Have a Dream” speech. Rustin dedicated his life fighting for peace and justice in America and around the world.

If you’ve never heard of Rustin (1912-1987), you’ve certainly seen his picture—he appears alongside Dr. King, John Lewis, A. Philip Randolph, and other luminaries in many of the iconic photos of the Civil Rights movement. As organizers of the 1963 March on Washington, Rustin and Randolph made the cover of Life magazine a week after the event. He later directed the AFL-CIO’s A. Philip Randolph Institute, forging an alliance between civil rights and the labor movement.

A lifelong pacifist, Rustin was also openly gay and, briefly in the 1940s, a member of the Young Communist League. In America’s virulently anti-Communist and homophobic culture, Rustin was never an entirely visible part of the movement he helped create.

Rustin was also an accomplished musician, using music throughout his life as an integral part of his activities as an organizer, protester, and advocate. He grew up singing in the African Methodist Episcopal church in segregated West Chester, Penn., and matriculated at Wilberforce University as a music major, where he toured as a tenor in the Wilberforce Singers.

While Rustin’s efforts for civil rights have been closely examined, and the LGBTQ+ community continues to celebrate his life and accomplishments, Rustin’s activities as a performer of early music and collector of antique musical instruments is still not well known. In the pages that follow, I document Rustin’s career and interests in music—an activity he used to support his lifelong goals of pacificism, racial equality, and justice.

Rustin’s 1952 LP release Elizabethan Songs & Negro Spirituals is a testament to his abilities as a musician and his deep knowledge of music history. It is also a document that reveals his unique engagement with the nascent early-music revival in New York City.

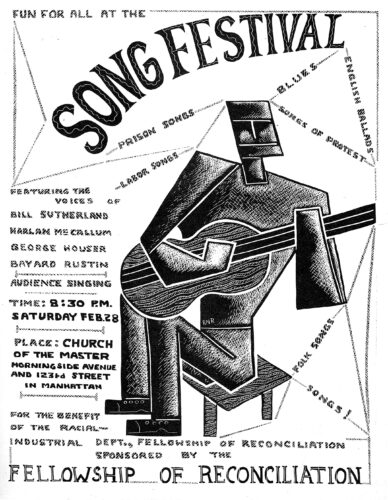

Elizabethan Songs & Negro Spirituals (ES&NS) is one of two LPs Rustin recorded for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), an interfaith peace organization founded in 1914 that would help lay the groundwork for anti-war and civil rights efforts over the course of the 20th century. Recruited by FOR in 1941, Rustin would subsequently travel the country and the world teaching, protesting, and catalyzing anti-racist activism as part of that organization. Rustin’s other FOR release, Twelve Spirituals on the Life of Christ, featured Rustin’s singing interspersed with readings from the Bible by James Farmer, another young Black activist recruited by FOR in the early 1940s. (Earlier his year, Parnassus Records released both these albums as Bayard Rustin – The Singer, available on Spotify and other streaming services.)

ES&NS features the juxtaposition of four “Negro spirituals” and eight “Elizabethan songs.” LPs presenting contrasting repertoires were somewhat common during the postwar decades. Examples include Josh White’s Ballads and Blues (Decca) and African American tenor Roland Hayes’ Six Centuries of Song (Vanguard), in which the A side features European medieval and Renaissance composers and the B side offers “Afroamerican religious and work songs.”

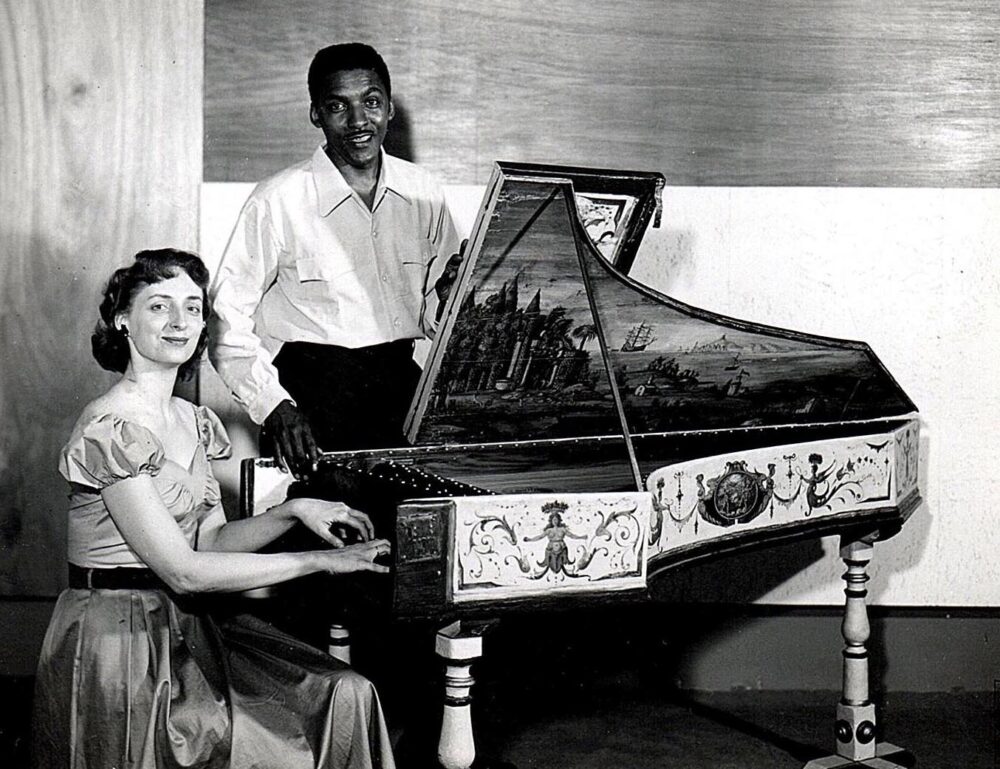

The programming of Rustin’s ES&NS may have spoken both to his love for Elizabethan (and other European) vocal repertoire, as well as to the explicitly integrationist culture and aims of the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Three of Rustin’s Elizabethan songs feature “lute accompaniments arranged and played by the singer himself,” while the remaining songs are either accompanied by one Margaret Davison on the harpsichord and piano (in the case of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen”) or performed a cappella. Program notes printed on the record sleeve are supplemented by a folded insert that includes lyrics and a few additional comments on each of the “Elizabethan” songs. Rustin did not include lyrics or program notes for the four spirituals, likely assuming that they would be sufficiently familiar to listeners.

An important influence on the nascent early-music revival in New York and Boston during the 1940s and 1950s were LPs of “folk” music that included selections of English and French Renaissance ballads. During the decades leading up to and including the 1950s, “Elizabethan” was used as a catch-all term to refer to a much broader musical repertoire than that strictly associated with Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) or even England. One of Rustin’s surviving notebooks from the period during which he was assembling the material for ES&NS lists 32 titles Rustin considered as candidates for the recording. The list contains the seven “Elizabethan” songs that appear on ES&NS plus such diverse titles as the medieval canon “Sumer is icumen in,” “Barbara Allen,” and several Renaissance French carols. In his liner notes to ES&NS, Rustin credits Arnold Dolmetsch, one of the founding figures in the early-music revival, for the edition of “Have You Seen But a Whyte Lillie Grow” that appears on the record.

Rustin placed his “Elizabethan” music in dialogue with his pacifist and civil rights activism

Music, Gandhi, and Non-Violence

But Rustin’s selection of “Elizabethan” repertoire reveals more than his evident familiarity with a range of historical sources. Rather than presenting early music for its exotic evocation of an imagined long ago and far away, Rustin placed some of his “Elizabethan” music in dialogue with the pacifist and civil rights activism that explicitly motivated the record’s release. “I Saw Her as I Came and Went,” placed prominently at the beginning of side B and described as an “Elizabethan song” of “unknown origin,” is actually a Rustin composition that celebrates a key element of Rustin’s activism. The text, it turns out, appears in no anthology of Renaissance poetry or balladry, but rather in Vedanta for the Modern Man (1951), a book of poetry and essays edited by Christopher Isherwood and published by the Vedanta Society of Southern California. Vedanta refers to the teachings of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, a 19th-century Bengali mystic and religious leader who inspired a worldwide movement of Hindu mysticism that quickly gained a toehold in the U.S.

Indian philosophy and spirituality, such as that practiced in the American Vedanta milieu, was an important element in the pacifist and social justice movements of the American post-World War II period. Rustin’s mentor A. Philip Randolph, for example, was a devoted follower of Mohandas Gandhi, whose successful campaign of non-violent direct action (NVDA) in India was carefully studied by American civil rights activists. By the late 1950s Rustin himself would become the acknowledged American authority on Gandhian NVDA, and he would be sent to Alabama to teach the young Martin Luther King, Jr. how to use non-violence as the central principle of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and later integration activism.

But in 1952 Rustin was still studying Indian philosophy and adapting the teachings of Gandhi, Vedanta, and other wisdom traditions to the challenges he faced as a labor and civil rights organizer. The text of Rustin’s “Elizabethan” composition is a poem by Frederick Manchester extolling Sister Lalita, a California heiress who would become revered as a nun in the Vedanta community in Southern California. It is this poetry that Rustin sings, accompanying himself with a haunting (and credibly Renaissance-sounding) lute part of his own invention.

Another of Rustin’s “Elizabethan” songs with connections to his work as an activist is “Lass with the Delicate Air,” credited to Michael Arne (1741-1786) and traceable to an arrangement published in the Songs and Ballads of the Olden Time (1898).

“Lass” was likely the most familiar selection among Rustin’s Elizabethan songs, having been recorded numerous times since Marcella Sembrich’s 1907 version on a twelve-inch shellac disc. Rustin may have chosen the song by virtue of its association with Josh White, arguably the most famous blues performer during the 1940s and a key Black figure attached to the folk revival, along with Huddie Ledbetter (better known as Lead Belly). White had included “Lass” on his record Ballads and Blues (Decca, 1946), which also included “Strange Fruit,” Billie Holiday’s searing account of a lynching that had recently galvanized attention to racial violence, and “John Henry,” a blues song about the African American folk hero. In fact, White’s Ballads and Blues, with its conspicuous juxtaposition of “white” and “Black” idioms, may have served as a model for Rustin’s Elizabethan Songs & Negro Spirituals.

When Rustin had first arrived in New York he had a minor role as a singer in the Broadway production of John Henry starring Paul Robeson in 1940. During the show’s short run, Rustin met Josh White, also part of the production, and subsequently toured and recorded as a member of Joshua White & His Carolinians, whose album Chain Gang (Columbia, 1940) described what many considered to be a form of modern-day slavery. Just a few years later, in 1949, Rustin would be made to serve on a chain gang in North Carolina after he was arrested during the Journey of Reconciliation in which 16 Black and white activists traveled across the South, challenging segregation in public transportation. These would later be known as the Freedom Rides. (And a few years later, Rustin’s essay “22 Days on a Chain Gang” would be published serially in The New York Post and would lead to the abolition of chain gangs in North Carolina.)

The success of Joshua White & His Carolinians’ Chain Gang led to their being hired as the house band at the first integrated nightclub in New York City, the Café Society located on Greenwich Village’s Sheridan Square. Café Society would host Billie Holiday’s first performance of “Strange Fruit” and would be a key site of the cultural foment out of which would coalesce the burgeoning Civil Rights movement.

So Rustin’s “Elizabethan” songs included both 16th- and 17th-century music drawn from scholarly editions (in the case of “Ah, the Sighs that Come from My Heart,” Rustin lists the shelf mark of the song’s manuscript source: British Museum, Royal mss. 58), as well as selections that spoke to the complex intersections of music and activism that were a key part of the post-WWII early-music revival.

In this regard, it’s worth remembering that Noah Greenberg, whose New York Pro Musica, founded in 1953, would introduce broader American and international audiences to early music, moved in similar leftist and activist circles as Rustin. (Rustin’s possession of Greenberg’s 1956 Elizabethan Songbook only hints at these connections.) In the 1960s Greenberg would invite African American performers Marvin Hayes (bass-baritone) and Frederick King (percussion) to join NYPM, and both musicians appear on several of the ensemble’s most iconic recordings for the Decca label.

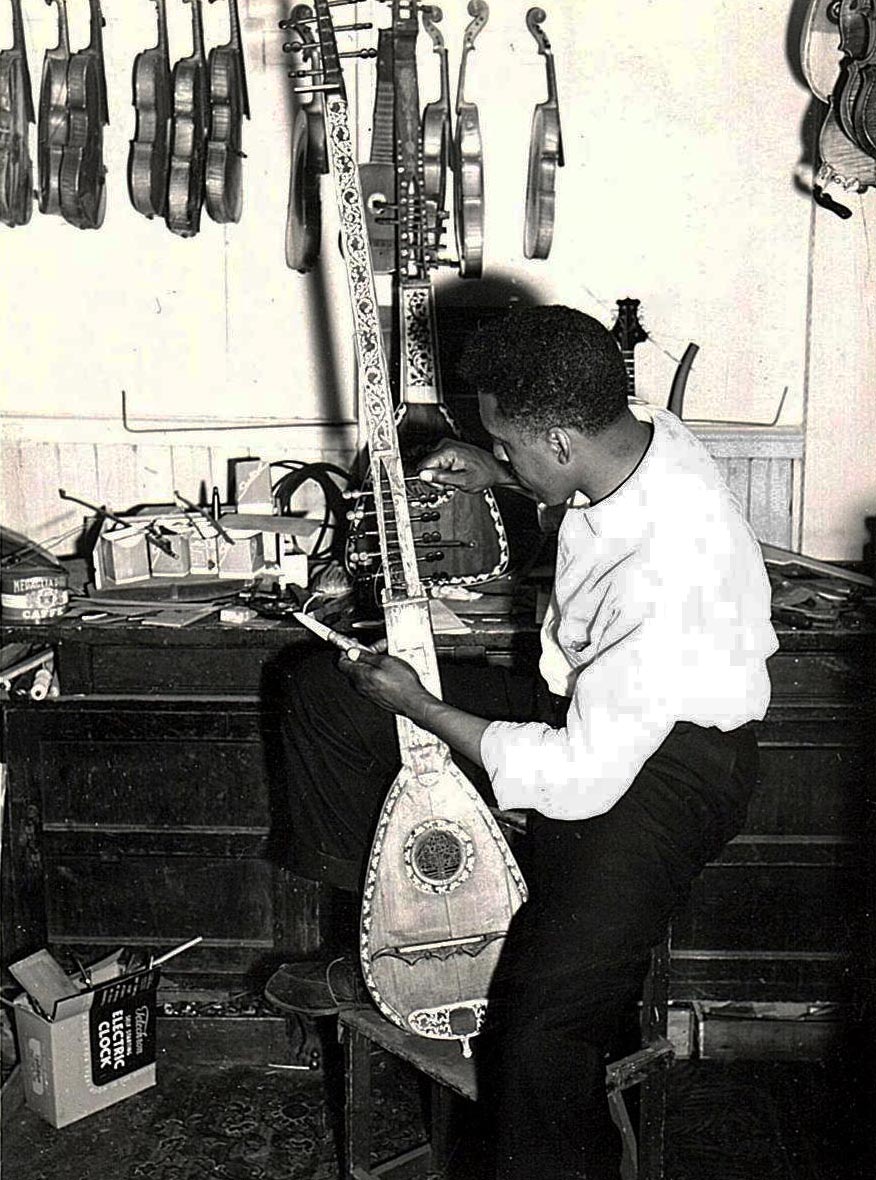

At the same time that Rustin was researching and preparing to record ES&NS he was beginning to build a collection of historical musical instruments that would grow to include several keyboards, lutes, guitars, and at least one viola da gamba. An avid collector, Rustin would eventually develop a reputation as a respected connoisseur with an unfailing eye for quality.

In Thomas Shaw’s book documenting Rustin’s formidable art collection, a New York antique dealer recounts that Rustin “could always walk in and immediately pick out the four or five best objects in his antiques shop.” At the end of his life Rustin’s collection of paintings, furniture, decorative objects, walking sticks, clocks, and other items numbered nearly two thousand. Shaw writes, “it was an extraordinary assemblage which filled every corner and available wall space, many shelves, drawers, table tops and closets of his home in New York City.”

‘Cultural heritage of Black Americas’

Rustin’s interest in old instruments may have initially been spurred by the gift of a lute while Rustin was imprisoned as a conscientious objector during WWII. Davis Platt, Rustin’s lover when Rustin was sent to Federal prison in Lewisburg, Penn., in 1944, recounts in Brother Outsider that while Rustin was incarcerated, “I somehow found a lute for him and he learned to play it all by himself in jail.”

Rustin’s deep love for Shakespeare and English history may have played a part in his initial interest in the lute. Photos of Rustin with this first instrument suggest that it was likely a lute guitar, a six-stringed instrument tuned like a guitar but built on a lute-like bowl of curved ribs that had been mass produced in Germany during the mid-late nineteenth 19th century. Undated photos from later in the 1940s and early 1950s chronicle Rustin’s developing knowledge of progressively more historically accurate lutes. Several photos show Rustin playing instruments with inlaid frets but more than six strings, and a striking series of images show Rustin repairing a theorbo. A later picture taken in Rustin’s apartment in Chelsea shows what appears to be a small, historical lute with ten pegs and double courses. The series of photos of Rustin adjusting the pegs on a theorbo in an unidentified instrument shop may corroborate accounts suggesting that Rustin also repaired historical instruments in his apartment on Mott St. in the 1940s, right around the corner from Margaret Davison and her harpsichord.

‘I somehow found a lute for him and he learned to play it all by himself in jail.’

The back cover of ES&NS specifies that “[Rustin] is accompanied in the five songs on this side by Margaret Davison, playing a 300-year-old harpsichord, restored and lent for the occasion by a friend and fellow collector of old instruments, Clifford Wheeler.” The statement is amplified by a photograph showing Rustin standing behind a decorated Flemish single with Davison seated at the keyboard. The instrument appears to be from the Franciolini shop, based on the distinctive decorations. Leopold Franciolini was an Italian antiques dealer and fraudster who infamously sold all sorts of spurious “historical” instruments—some constructed from parts of actual historical instruments!—during the decades around 1900. Museum collections of antique instruments (including New York’s Metropolitan Museum) invariably still hold spurious exemplars sold by Franciolini, which are now instantly recognizable to experts.

But who was Rustin’s “friend and fellow collector of old instruments?” Wheeler Piano Service of Pigeon Cove, Mass., was still listed in a 1982 issue of the Fellowship of Makers and Researchers of Historical Instruments, but Wheeler’s activities earlier in the century are hard to trace. Wheeler is mentioned as the “traveling harpsichord technician” for a concert tour of Asia in 1956 by New-York based harpsichordist Sylvia Marlowe. Marlowe would be appointed the Professor of Harpsichord at the Mannes College of Music around 1950 and was known to host gatherings with her Russian émigré husband at their Manhattan apartment that included W.H. Auden, Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, and other artists and intellectuals.

A “scene” begins to come into focus during the late 1940s and 1950s that connects performers of early music, such as Noah Greenberg and Sylvia Marlowe, to Clifford Wheeler and the anglophile Bayard Rustin, and including, certainly, W.H. Auden. This was a vital moment in the revival, specifically for historical keyboards. Wanda Landowska was nearby in Salisbury, Conn. beginning in 1947, and Frank Hubbard and William Dowd would open their shop in Boston in 1949. Marlowe would start teaching harpsichord at Mannes in (likely) 1948, and the Belle Skinner collection of historical instruments, including numerous important keyboards, would move to Yale in 1959. (Rustin’s library contained a copy of the 1933 catalog of the Belle Skinner collection.)

In 1952, Rustin purchased an “English clavichord” from Edmund C. Legg & Son, Antique Furniture and Early Keyboard Instruments, Cirenchester, UK. Several letters document the purchase of a “clavichord in pine case on folding stand of oak” for $181 as well as the return of the instrument to England for repair. Rustin may not have yet known the young Frank Hubbard, whom Rustin would approach years later with questions about the restoration of a Barak Norman viola da gamba now owned and played by Laura Jeppesen. According to Jeppesen, Rustin had found the viol in an antique shop in New York and approached the Hubbards, who had the instrument sent to Andrew Dipper to be restored in England.

A series of letters from 1954 documents Rustin’s purchase of two historical guitars, neither of which I’ve been able to trace since they left Rustin’s possession. An excerpt of one letter (from the dealer G. Viccari in London on Oct. 12, 1954) reads:

“Dear Mr. Rustin,

I thank you for your inquiry for an old lute, with the neck at right angle, these instruments are very rarely seen, and they sell at high prices – I am sorry I haven’t one – but I have two old guitars – one has the label of Franciscus Stradivarius 1740, it has the original short neck and nine frets of ivory one missing. It was made to take 8 strings, it has only original pegs, the back is of plain maple also the sides, it has a crack in the belly and is unglued all round, wants repairing, but it’s very interesting that it was made by the son of the Greatest Violin Maker Antonio Stradivarius…it’s worth repairing [phrase underlined] – the price is £25…”

Subsequent letters indicate that Rustin purchased the Stradivarius guitar.

The correspondence and images related to Rustin’s instrument collection shows that he developed a considerable expertise in historical European musical instruments, and his library included numerous important references then available on historical instruments, such as Philip James’ Early Keyboard Instruments (1960) and Nicholas Bessaraboff’s detailed organological study of the instruments at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (1941).

Shaw recounts that Rustin once flagged down a curator at a major museum’s exhibition of musical instruments to have them correct a mistaken label on a historical keyboard. Interestingly, Rustin de-acquisitioned his instruments during the later decades of his life. In an interview in 1970, he explained, “I think that people often collect one thing at one time of their lives, have an intensive experience until it exhausts itself, and then go on to something else. The things I have changed and they change me, and as I change so do the works. It’s a very reciprocal relationship.”

Rustin ‘explored early music both for its historical richness as well as for its capacity to communicate to contemporary audiences preoccupied with equality, peace, and the universal sanctity of our shared humanity.’

This “reciprocal relationship” might also be extended to describe that between the performer and (historical) musical repertoire. Part of the fetishization of “authenticity” that came to characterize the field of early music in later decades entailed an implicit denial of the power of old music to speak to the contemporary moment. As I’ve researched Rustin’s activities in the early–music revival of postwar New York City, I’ve been struck by the ways in which he seems to have explored early music both for its historical richness as well as for its capacity to communicate to contemporary audiences preoccupied, like Rustin, with equality, peace, and the acknowledgement of the universal sanctity of our shared humanity.

In addition to his recordings (such as that of Elizabethan songs made as a fundraiser for the Fellowship of Reconciliation), Rustin used music extensively in his thousands of addresses, workshops, lectures, and protests. The beauty of his voice and facility as a singer and player of the guitar, mandolin, and lute allowed him to draw on a rich and varied repertoire appropriate to the moment, message, and audience.

Making art, Rustin wrote in an unpublished essay that would serve as the basis of a speech before the NAACP in 1970, was essential to the fight for freedom. “The Negro freedom struggle isn’t merely political, but it is the struggle of an oppressed people to realize their full humanity, to make their heritage part of their living experience; and ultimately to develop a consciousness of their inviolable dignity. The black artist is a part of this struggle in the very act of his imaginative creation.”

Though Rustin revered African American musical traditions (such as the four spirituals that end ES&NS), he recognized that even Elizabethan music could testify to the “inviolable dignity” of Black people and humanity more broadly. In a statement that echoes his “reciprocal relationship” between collector and artifact, Rustin wrote, “It is essential that white Americans understand the black experience since it has been so much a part of them and, of course, they have been so much a part of it. If the races in America will ever be truly reconciled to each other, I think it will come about in part because the black artist has used such tools as irony, satire, comedy, and tragedy to explain the profound complexity of the black experience to all Americans.”

For Rustin, Elizabethan music and antique European instruments were “part of” the cultural inheritance of Black Americans, just as those songs and instruments were “changed by” the modern voices and hands that touched them. Throughout his life, Rustin stayed true to a vision of American democracy built on the acknowledgement of unity, of the shared humanity of Black and white people. He expressed this certainty again and again: in his debates with Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, in his work with FOR and A. Philip Randolph, and, powerfully, in his comments following the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968.

Given Rustin’s lifelong confidence in the power of music to “explain the complexity of the black experience to all Americans,” one might reflect on his deliberate juxtaposition of Elizabethan songs with Negro spirituals in his powerful words to a mourning nation:

“I believe that Dr. King’s death, like the death of Lincoln, will force this nation to decide whether we are going to create two societies or one, whether this is going to be a white society on the one hand and a black one of the other, a rich society on the one hand and a poor one on the other. If he dies for that, his death ultimately will be an important event for the democratization of this nation.”

Next year, Netflix plans to release a film on the life of Bayard Rustin. For this article, special thanks to Rustin’s partner, Walter Naegle, as well as Patricia Ann Neely, Margaret Chisholm, Sara Davison, Laura Jeppesen, and Mark Kroll.

Loren Ludwig is a viol player and music researcher based in Baltimore. He holds a B.Mus. from Oberlin Conservatory and a PhD in musicology from the University of Virginia. See lorenludwig.com.