Four Japanese boys, students at a Jesuit school, were sent on an eight-year tour of Europe. This little-known story is as complicated as it is fascinating.

Lyracle, a Boston voice-and-viol ensemble, programmed music associated with the Tenshō Embassy. But tracing this fraught history meant accepting a host of practical, historical, and ethical challenges.

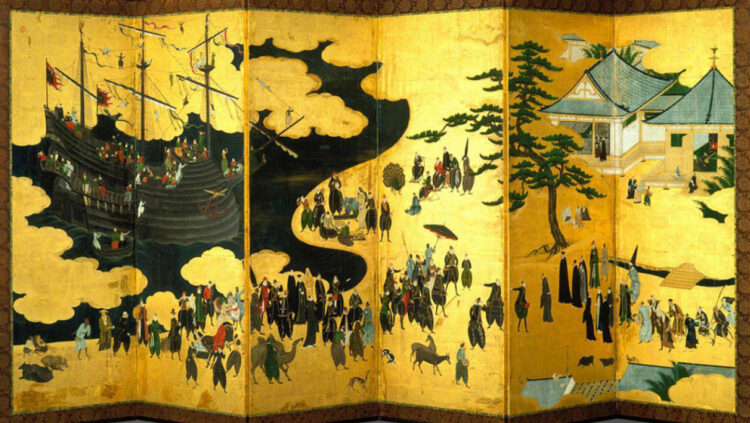

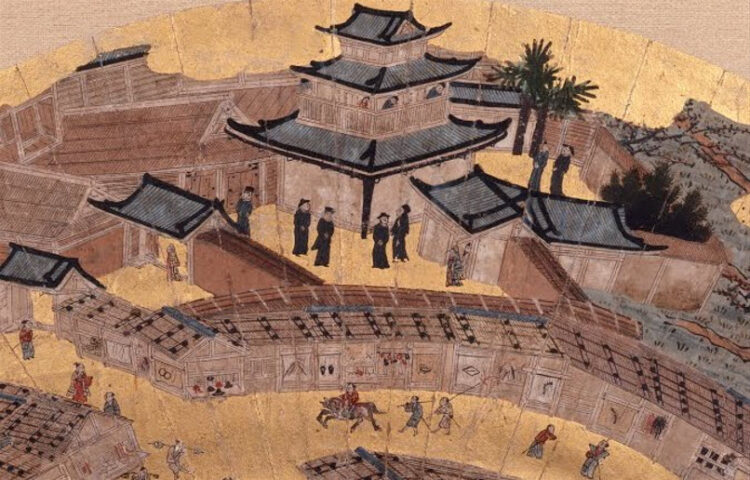

In 1582, four teenage Japanese boys of noble birth set sail from Nagasaki to Lisbon. They were students at the Jesuit school in Kyushu and were sent on a tour of Italy and Iberia as ambassadors of three Japanese daiymo, or feudal lords, who had converted to Christianity. Known collectively as the Tenshō Embassy, their names were Mancio Itō, Michael Chijiwa, Martin Hara, and Julio Nakaura. Music was an essential component of the Embassy’s eight-year trip to and from Europe and played an essential role in the Jesuit mission in Japan, which lasted from the first Jesuit’s arrival in 1549 to the expulsion of the Jesuits by Japan’s Edo government in 1614.

When Lyracle co-director James Perretta and I — viola da gamba and mezzo-soprano — first encountered the Tenshō Embassy, we were astonished to learn that the history of the viol included a thriving culture of European music-making in 16th-century Japan. In retrospect, this reaction seems foolish. Given the global expansion of European colonial and conversion enterprises in the 16th century, why wouldn’t there be viols in Japan?

In our surprised responses, we saw an opportunity to address a gap in shared knowledge about the people who participated in what we now call “early music.” But the history of these little-known musicians is as complicated as it is fascinating, and addressing this gap through Lyracle’s program Musicians of the Tenshō Embassy has meant accepting all of the practical, historical, and ethical challenges that come along with it.

A little background on how we got here. Lyracle’s inaugural concert, in 2018, was in the “cantar alla viola” tradition, accompanying a single voice with a single viol. While we delighted in discovering music by composers like Robert Jones and William Corkine, we realized that we would quickly exhaust this repertoire, and, with few exceptions, we would box ourselves into music from early modern England, wonderful as it may be. With this realization, we made the paradigm shift from asking, “who wrote for voice and viol?” to asking, “who throughout history participated in the practice of making music with voices and viols?” When a global pandemic gave us innumerable hours to search for answers, we stumbled upon the Tenshō Embassy.

Given the global expansion of European colonial and conversion enterprises in the 16th century, why wouldn’t there be viols in Japan?

We learned about the Tenshō Embassy in Japanese researcher and viol player Yukimi Kambe’s article “Viols in Japan in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries,” published in a 2000 issue of the Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society of America. We did a bit of digging to see if other ensembles had done a program that squarely focused on the Tenshō Embassy or European musical practices in early modern Japan. We found none. We have since learned about a few events by ensembles based in Europe and Asia, but, at the time, we wondered if there was even enough existing scholarship to curate a full concert of music.

Historical Realities

While boys in Jesuit schools in 16th-century Japan sang and played many instruments, as a voice-and-viol ensemble we were primarily interested in the history of their singing and viol playing. Through extensive archival work, Kambe identified numerous sources that mention the viol. Add to this more than 80 publications about the Tenshō Embassy’s activities abroad, printed in at least five European countries during and shortly after their sojourn, and there’s plenty of source material to work with. We were excited to find the kind of first-hand accounts that would make it possible to effectively celebrate the boys’ musical experiences and accomplishments through performance; however, it was also immediately apparent that this key information is inextricable from bigotry and xenophobia. Unfortunately, none of our sources were written by members of the Tenshō Embassy or other boys at Jesuit schools in Japan. What survives is a wealth of reports penned by Iberian and Italian Jesuits.

Once we determined that we could access enough information to curate a program about the Tenshō Embassy and their peers at Jesuit schools in Japan, we had to ask ourselves if it were possible to create a program that celebrates their musical abilities while also giving appropriate weight to the historical realities that surrounded them.

We decided that the only way forward was to put historical context first and music second. Rather than attempting to erase historical realities, our goal was to bring them to the fore. For the performance, we hired a narrator who served two functions. The first is to read short, translated excerpts from primary sources. We selected passages that best highlighted the boys’ music-making, particularly on the viol, while objectively answering “who, what, when, where” questions. We know the names of most of the authors of our selected passages, but we chose not to include them since our goal was to emphasize the experiences of a group of people whose names remain mostly unrecorded. We also chose to exclude passages that make overt value judgments on non-European peoples and musics. Second, our narrator sometimes switches into a more commentative style to provide context about the goals of the Jesuit missions in Japan and the Tenshō Embassy’s European tour.

‘We decided that the only way forward was to put historical context first and music second’

Once we chose the passages that would form the backbone of our program, we selected one or more pieces relevant to each reading. This proved to be difficult, especially for an ensemble with a budget for just four musicians. The only extant composition that we are sure the Tenshō Embassy encountered is a mass by Andrea Gabrieli for 12-16 performers, which the Embassy heard at San Marco in Venice.

To illustrate reports about the Embassy’s time in Europe, we selected music for its geographical and chronological relevance. We found that Ginés de Morata was a prominent court composer in Vila Visçosa, Portugal, in the 1580s, so we chose two charming songs of secular polyphony by de Morata to accompany this 1584 report from Vila Visçosa: “During the two and a half days they [the Tenshō Embassy] spent there, Senhora Dona Catherina granted them audiences four or five times, as she desired…In order to show her sincere welcome, she offered lovely music, sung quietly. The duke found that the Japanese gentlemen could play musical instruments. He had a harpsichord and viols brought into the room. Those who heard the boys play and sing to a viol and harpsichord all admired them greatly.”

At times, we were able to narrow our selection with more specific criteria. Thus we selected a Te Deum by Roman composer Felice Anerio to accompany this 1585 report about the Embassy’s visit to Rome: “The cavalry accompanied them into the city, heralded by trumpets and followed by a public eager to catch a glimpse of them, some who awaited them at the city gate, and others who ran to followed them, such that they were swarmed by a crowd of people. They went straight to the house of the Jesuit Society, where the father and brothers awaited them at the door. The light of torches warmly surrounded the father, whom the Japanese greeted with a grand reverence upon their arrival. With a throng of people behind them, they were ushered into the church, where with closed doors, a beautiful Te Deum laudamus was sung.”

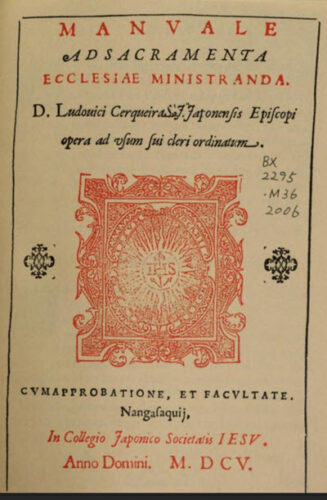

Choosing music related to reports that recount activities in Japan was a bit more complicated. There is a dearth of printed music or even musical inventories from early Jesuit communities in Japan, likely attributable to the destruction of churches and schools by the Edo government in the 17th century and the American bombing of Nagasaki during World War II. One of the few musical sources that we can trace back to these communities is Manuale ad sacramenta ecclesiae ministranda (A Manual for the Sacraments to Serve the Church). The publication contains 17 chants and was printed in Nagasaki in 1605 with a European press that was gifted to the Tenshō Embassy during their time abroad. We selected the chant “Sicut cervus.”

In addition to printed music, we also learned about orally transmitted liturgical music with links to early Japanese Christian communities. The chant “O gloriosa domina” is one such example. There is much to discover about how this chant with Iberian origins was passed down in Japanese Christian communities to the present day, a line of inquiry that Makoto Harris Takao takes up in his forthcoming monograph, The Clef and the Cross: Music and Kirishitan Transculturation in Sixteenth-Century Japan. Harris Takao, a professor of musicology and East Asian languages and cultures at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, also led us to several secular published Iberian music books that include instrumental pieces based on this chant melody, which we decided to incorporate in an arrangement for solo viol.

A History That’s Incomplete

Although our search for specific music that we could trace back to early Chrisitan communities in Japan resulted in just two selections on our program, broadening our search to include records from Jesuit communities throughout Asia proved to be fruitful. The Jesuits were a global organization, and Jesuit missions throughout Asia were in close communication. With this in mind, we programmed two songs from Tempio armonico della beatissima vergine (Harmonic Temple of the Most Blessed Virgin), an anthology of devotional songs printed in Rome in 1599 and included in a library inventory from a Jesuit mission in Beijing. By looking at a Jesuit library catalogue in Macau, we were also able to program excerpts from Portuguese composer Duarte Lobo’s Masses for 4, 5, 6 and 8 voices.

Following the expulsion of the Jesuits from Japan in 1614, some Catholics in Japan fled to other parts of Asia, where Christian communities continued to thrive. One such city was Goa, India, which, unlike Japan, was under Portuguese colonial rule. A 1683 report from Goa specifically mentions Giacomo Carissimi: “In that city of Goa I enjoyed many times listening to very beautiful music for the feast days, especially that of St. Ignatius Loyola, which was celebrated with seven choirs and the sweetest sinfonie in the Professed House of the Fathers of the Society. When I said that it was like being in Rome, I was told that I was not mistaken, because the composition was that of the famous Carissimi that was brought to that place. I cannot believe how musically proficient the locals are and with what ease they perform. There is no town or village of the Christians which does not have in its church an organ, harp, and a viol, and a good choir of musicians who sing for festivities, and for holy days, Vespers, masses and litanies, and with much cooperation and devotion.” Our ensemble may not have the resources for seven choirs, but we found a liturgical piece by Carissimi that we could effectively perform with small forces.

Although we don’t have direct evidence that music by Anerio, Lobo, or Carissimi were present in Japan, we know that they were deemed important enough to transport to Asia. Given the global nature of the Jesuit operation, we felt comfortable inferring that these or very similar works could have circulated in Japanese Catholic communities.

In his 2009 article “The Dissemination and use of European Music Books in Early Modern Asia,” published in Early Music History, David Irving writes, “attention has been devoted to the circulation of notated musical commodities between Europe and the Americas, but the African and Asian contexts of this phenomenon remain fields that are, as yet, virtually untilled.” He continues, “Of course, when entire libraries were shipped, they may have contained some more dated works. But given the high cost of printed books in the first place, and the trouble in subjecting them to inquisitorial censorship before their transportation halfway around the world, it is likely that only the newest and most useful works were taken.”

We took Irving’s words to heart when working with textual sources that aid in our storytelling but provide little information to guide musical selections. For example, the tenuous relationship between Toyotomi Hydeoshi (the most powerful feudal lord in Japan) and the Tenshō Embassy is essential to our program narrative, but readings that illustrate their interactions provide no musical specificity.

Take the following 1591 excerpt in which Tenshō Embassy performs a concert for Hideyoshi after they had returned from Europe: “At last, Toyotomi returned to the visitors. The dishes had already been taken away. They talked of various things, and he said that he wanted to hear the four gentlemen play some music. Then the musical instruments were brought, which had been prepared in advance. The four gentlemen began to sing and play the harpsichord, the harp, the lute, and the rebec. They performed very gracefully because they had learned much in Italy and Portugal. He listened to them with great attention and curiosity. He ordered them to perform three times on the same instruments. Then he took each instrument in his hands, and asked the four princes questions about the instruments. He further ordered them to play the viols and the hurdy gurdy. He examined them with great curiosity. He told various things to the gentlemen, and said that he was very happy to find them to be Japanese.” Relying on informed conjecture, we selected pieces representative of music that the Embassy could have plausibly encountered in Italy or Iberia and performed for Hideyoshi back in Japan.

For better or worse, it was hard to get hung up on practical risks. There was a lot more at stake.

But working with informed conjecture means that you can’t just pull the score that you need off the shelf. For example, there’s a reading from 1565 that mentions the boys playing a Salve Regina with viols. The only Jesuits in Japan in 1565 were Portuguese. So we needed a Salve Regina with no more than four parts that could have been known to a Portuguese Jesuit and brought to Japan by 1565. Each piece on this program required a hunt, and several of them, including the aforementioned Salve Regina, required transcription and/or transposition. There were many that we did not hear in completion until the first rehearsal, which, as ensemble directors, was a big risk to assume.

For better or worse, it was hard to get hung up on practical risks. There was a lot more at stake. To present a program that puts history first, you have to accept that, despite your best efforts, the history you present will be incomplete. Perhaps the most glaring example in the case of Musicians of the Tenshō Embassy is the total absence of well-documented musical blending of European and Japanese practices in worship and devotion. When you’ve worked so hard to acquire knowledge on a certain subject, it can be challenging to take a step back and decide that you cannot practically or ethically communicate it.

We hoped that by carefully holding on to and letting go of the right bits of historical knowledge, we could communicate a fraught history to audiences in a way that honors the lives and achievements of musicians who might otherwise remain unknown.

Ashley Mulcahy is a Boston-based mezzo-soprano and graduate of the Voxtet Program at the Yale School of Music and Institute of Sacred Music. She sings with numerous ensembles and co-directs her own voice-and-viol ensemble, Lyracle.