The modern Historical Performance movement has been around for about as long as the distance between the B-minor Mass and the Ninth Symphony. A lot of changes took place in those 75 years.

Is it possible that early music is over, and we just haven’t realized it? There has been a lot of hand-wringing lately about the reduction or closure of early and/or historical performance programs associated with universities and schools of music. The apparent lack of growth in many areas — even as many major institutions and presenters appear to be continuing without apparent problems — gives the pessimists the confidence they need to start drawing up the death certificate.

It’s true that a few academic programs are being reduced in various ways. In some cases, especially Indiana University, what appears disastrous to our field is really part of a much larger cost-cutting agenda. It’s not just IU’s Historical Performance Institute ending its degree programs, the issue is all across the university and many other universities: a program of rationalization and efficiency, either required by the federal government or enacted by the state (or the university) proactively to forestall an even worse outcome.

It’s disastrous for education and society, but in truth nobody here is really picking on early music.

There is no clear picture of where this will end. As a degree-holder and retired professor at Harvard, a target of the current administration, I tremble not only for early music but for cancer research, for our increased understanding of Alzheimer’s disease, astrophysics, and indeed the increase of knowledge among humankind…

And aging pioneers: The Oberlin Baroque Performance Institute celebrated 53 years this summer, and Cathy Meints, Lisa Crawford, Michael Lynn, and Marilyn McDonald were all there, as they were there at the beginning. They are going strong — and long may they do so! — but they are not the young lions anymore. Marty Pearlman celebrated 50 years at Boston Baroque, which is now seeking his successor. Cathy Fay has run the Boston Early Music Festival for almost as long as I can remember. We owe them all a huge debt. And there are institutions that have successfully effected transitions from founding leadership to second- and third-generation success. It can be done.

As to lack of growth, I suggest this on the basis of almost no evidence, but it seems to me that we have distinguished institutions, like major presenting organizations (Music Before 1800, BEMF, others), substantial performing groups (Handel and Haydn, Tafelmusick, Philharmonia, Boston Baroque, others), but in recent years not much in the way of major new organizations or ensembles. (Apollo’s Fire’s expansion into Chicago is almost the exception that proves the rule). I don’t notice an increasing demand for early-music events on traditional concert series, or a sudden vogue for Gregorian chant.

And so, perhaps we should start writing the obituary; perhaps this column is the obituary.

But does anybody here believe that?

I certainly don’t. First of all, because of the music. The music we love, or at least those small parts, that we know and treasure, of the almost-infinite expanse of music of the past gives us endless material for listening, performing, studying, grooving. That music is there, and it’s not going away. Indeed, we keep discovering more. And secondly, because it’s not from the great established institutions of historical performance (forgive me, dear H&H) that the cool new ideas and the new repertoires and the crossovers and the multimedia performances and the things that I can’t even imagine will come from. They will come from people we haven’t heard of yet, groups that are just forming, performance ideas and styles that are being woodshedded and workshopped somewhere, perhaps right now.

I think we can expect, if not a revolution, at least a freedom, an exhilaration, a new age to succeed the old. After all, the modern HP movement has been around for about as long as the distance between the B-minor Mass and the Ninth Symphony. A lot of changes took place in those 75 years or so, and there’s no reason to expect our activities to be rooted in imitation, copying, or changeless repetition.

I think we’re on the move, and if we keep our ear to the ground (or wherever it is you keep your ear to listen for the future), we will hear the preliminary rumblings of some wonderful new things in our old world.

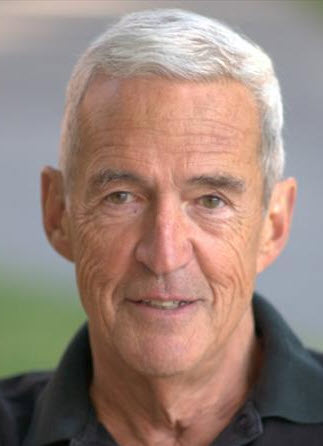

Thomas Forrest Kelly is Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music at Harvard, and previously directed early-music programs at Wellesley, the Five Colleges, and Oberlin. He is past president and a longtime board member of Early Music America and the author, most recently, of Melisma: Wordless Song in Medieval Chant (Oxford Univ. Press).