This article was first published in the January 2025 issue of EMAg, the Magazine of Early Music America

A keyboardist reflects on growing up Jewish and finding connections in early music

Should we rewrite Bach? ‘Singers don’t want to sing this; I don’t want to hear them sing it.’

A famous story in the Hebrew Bible describes Jacob in the wilderness wrestling all night with a mysterious being, perhaps an angel. When morning comes, the being blesses Jacob with a new name, Israel, often translated as “one who wrestles with the Divine.” This tale encapsulates an essential part of my own Jewish heritage: continually questioning, turning ideas over and over, and learning from the ongoing discussions of past and present scholars. This “wrestling” can take the form of Torah study just as it can take the form of debates over historical performance practices, contextualization of music from the past, and even what to do with problematic, or hateful, texts in that music.

In our time of rampant antisemitism, I set out to learn more about some of the Jewish leaders in early music. Although the field is becoming mainstream, I knew that my questions might not yield easy answers. But what surprised me was how many Jewish musicians from earlier generations were steeped in social consciousness.

I come from a family of leftist Jewish intellectual atheists. My grandparents were among the hundreds of thousands of Jews who fled Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century. There were many professional musicians in my extended family: pianists, string players, and a conductor. Unlike the rest of my family, I was always drawn to Jewish religion, spirituality, and culture. I was also drawn to early music and historical instruments.

When I began studying early music in the 1980s, all of my teachers and most of my classmates came from white Protestant backgrounds. Perhaps because I had been taught by my mother not to “seem too Jewish,” I eagerly adopted the attitudes of my peers. But the field that I leapt into was a far cry from the counter-culture vision of folks “who sat in boxes breathing in the darkness under the bridge, and rose up to build harpsichords in their lofts,” as described by poet Allen Ginsberg in his 1956 masterpiece Howl.

One of the performances that sparked my childhood interest was a touring production of Le Roman de Fauvel by the Waverly Consort around 1978. It was only in researching this article that I learned that its co-founder and director, Michael Jaffee, was Jewish and came from a background similar to my parents. Recorder player and Gotham Early Music Society founder Gene Murrow worked with Jaffee in the 1980s. When I asked him if they ever talked about being Jewish, he said, “The word ‘Jewish’ never passed our lips. Maybe he didn’t know I was Jewish. I don’t know how I knew that he was.”

Gene’s father had changed their family name from Meyrowitz to Murrow at a time when medical schools in the U.S. had limits on the number of Jews they would accept. “Meyrowitz” had been rejected repeatedly, but “Murrow” was accepted. I only realized that Gene Murrow was Jewish when we happened to be invited to the same Passover Seder. My own parents followed a practice typical of many U.S. immigrant families, giving their children British names like Byron in an effort to downplay their ethnicity.

‘I’ve been waiting for you’

I sometimes wonder how different my experiences of early music might have been if I’d had Jewish mentors in my early years. I met pioneering harpsichordist Laurette Goldberg in my late 20s and performed on her recital series at MusicSources in Berkeley, but never made an effort to know her. Now I was eager to talk to some of her distinguished former students.

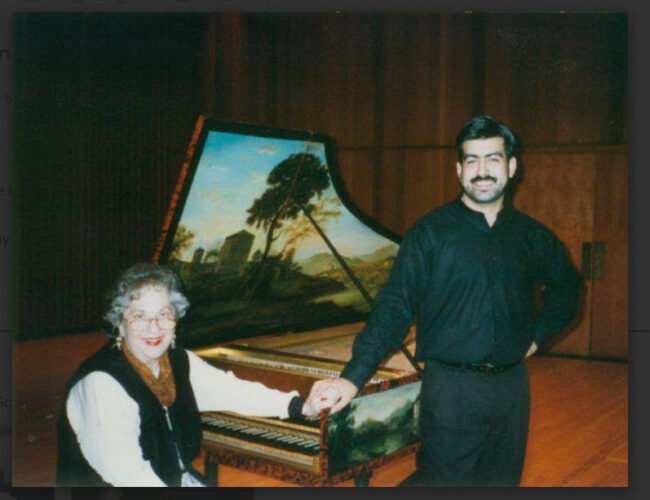

Harpsichordist Yonit Kosovske described her connection with Goldberg as having “a grandmother-granddaughter dynamic.” They shared Yiddishkeit, a love of Jewish identity and culture. In 1994, after several months as a student in Goldberg’s “harpsichord for pianists” class at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, Kosovske asked if she could become a harpsichord major. Goldberg replied enthusiastically, “I’ve been waiting for you!” Goldberg invited Kosovske to live and work at MusicSources for a year and took Kosovske under her wing “almost like an apprentice,” bringing her to weekly concerts and introducing her to other renowned artists.

Gilbert Martinez also apprenticed with Laurette Goldberg and eventually succeeded her as director of MusicSources, a role which he has since passed on to harpsichordist JungHae Kim. Martinez met Goldberg as a 13-year-old when her newly founded Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra performed in his hometown of Bakersfield, Calif. Martinez described her as “a big ball of energy. She absorbed me. We were in love!”

Goldberg was one of the first Jews Martinez had ever met. I asked whether her Jewish identity ever came up, and his response was “Always. Always!” He once showed up to a lesson prepared with Heinrich Scheidemann’s Englische Mascarada, oder Judentanz and was told “You can’t play that: It’s antisemitic.” Then he had to convinced her that it was not an ugly caricature of Jews but rather a tribute to the Jewish dance masters who were then active in England. He had done his research, so she was willing for him to play it.

As Martinez saw it, “you weren’t arguing Talmud but you were discussing music.” He added, “I came playing the harpsichord, but the lessons were more about life than about the notes.”

When early music was more about historical authenticity than making socio-political statements

Martinez had been blown away by the Philharmonia concert he heard in Bakersfield, how the performers stood, played from memory, wore “weird outfits” instead of traditional classical concert garb, and “danced right off the stage.” Flutist Stephen Schultz, who has played in Philharmonia since those early days, acknowledged that “it was formed as a conductorless ensemble because it was a rebellion from the dictatorial conductors from the past.” This willingness to challenge the status quo, this expression of unbounded joy, resonated deeply with my Jewish experience.

Martinez also talked about attending a concert of Joel Cohen’s Boston Camerata performing Chants de L’Exile, a program of music by European Jews between 1200 and 1600. Martinez acknowledges that Cohen was “way ahead of his time.” My own first recollection of Cohen and the Boston Camerata — he led the ensemble from 1968 to 2008 and is now artistic director emeritus — was their powerful anti-war recording L’Homme Armé, from 1985, which came out at a time when it seemed to me that early music was more about historical authenticity than making socio-political statements.

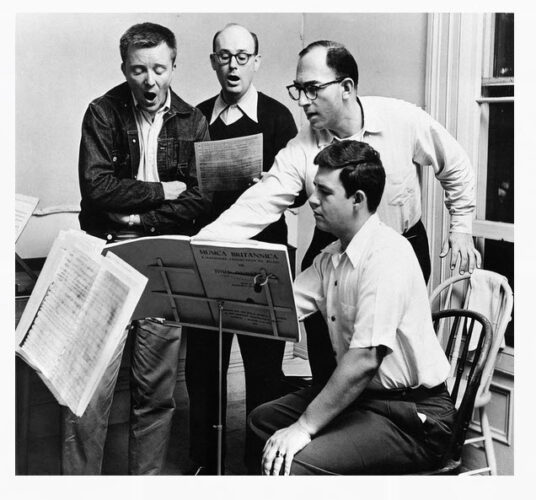

As the Boston Camerata celebrates its 70th anniversary, I talked with Cohen about the early-music movement of his generation and some of its more counter-culture aspects. “There was a kind of rebelliousness, yeah,” he said. Cohen cited Noah Greenberg, who founded the New York Pro Musica in 1952, as his first model. “We talked about the philosophy of it. He was a union organizer — leftist, Jewish, secular. He said, ‘Well, I don’t believe in heaven, so I think I’ll have a good time right here. I’ll do the music.’ His secular Judaism influenced his left-wing politics.”

There were a lot of Jews in the New York early-music scene then. Cohen brought up the viol player Judith Davidoff, who also came from a social-justice perspective, and wind players Bernard Krainis and Shelly Gruskin.

Cohen acknowledged that being Jewish had a lot to do with the repertoire he chose, starting with using a Hebrew cantillation to open the Boston Camerata’s classic 1974 recording, A Medieval Christmas, and including several programs of Jewish music, as well as spending time in North Africa studying Arab-Andalusian music.

‘It’s part of self-discovery’ says Joel Cohen, it’s ‘part of discovery of musical historical context.’

In the late 1990s, Cohen went to Fez, Morocco, to study Arab-Andalusian theory and to practice with master musician Mohamed Briouel, in preparation for performances and recordings of the 13th-century Cantigas de Santa Maria. To highlight the intercultural aspect of that Medieval Spanish repertory, Cohen assembled a group of singers from various European and North African backgrounds to join an Arab-Andalusian orchestra and additional Ashkenazi Jewish instrumentalists from the United States. “The Moroccan Jews used the same tunes as the Muslims, just with different words. On a very personal level, I came to the awareness that part of me, older and perhaps deeper than the Eastern European and American strains, was Middle Eastern. It’s all part of self-discovery as well as part of discovery of musical historical context.”

Social consciousness has always played a major part in Cohen’s work. Whether exploring Arab-Andalusian music, Black music in the Americas, or the tragedy of war, he is always “trying to make the world better — which is, in some sense, a Jewish mission.” As he points out, “respect for learning is part of Jewish tradition.” Citing performance practices from Eastern and Central Europe to North Africa and Persia, he suggests that “Jews have been very important in preserving many corners of musical repertoire.”

‘How different are we really?’

Robert Eisenstein, director of the Folger Consort, is another leader in our field with a Jewish background and an emphasis on social justice. Eisenstein was a viol student of Judith Davidoff and later of the Berkeley musicologist Richard Taruskin, whom he described as “a New York intellectual Jew, interested in just about everything he could get his hands on in terms of reading and of music.” Eisenstein described an “epic night” with Taruskin and others in which they played through the entire Odhecaton (a 1501 collection of secular polyphony) from original notation, all in one night. That reminded me of the Jewish festival of Shavuot, in which there is a tradition of staying up all night to study Torah, which Eisenstein then likened to a tradition he learned about from South Indian Carnatic musicians, in which a group of women would sing one song all night.

Eisenstein has been passionate about exploring the intersection of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian musicians in 13th-century Spain, most recently in collaboration with Palestinian scholar and oud player Ronnie Malley. “We started the program with what we called an Abrahamic invocation — snippets of prayers from all three countries in the same mode. You come to the conclusion that, how different are we really?” he said. Knowing that many Jewish musicians and audience members were feeling especially vulnerable since Hamas’ brutal October 7, 2023 attack on Israel, he continued, “The audience really appreciated it.”

But in a similar program he directed in 1996 at Washington’s National Cathedral, Eisenstein “made the mistake of programming one of the Cantigas that is very” — he paused with a heavy sigh — “I don’t know if it’s antisemitic…it is what it is.” The Cantigas de Santa Maria tell stories of miracles performed by the Virgin Mary, and the song in question begins with a child singing the Gaude Maria, with the words “weep with shame, miserable Jew” and ends with a Jew being burned in the town square.

In spite of Eisenstein’s efforts to contextualize the piece and its horrifying text, and in spite of Eisenstein himself being Jewish, several listeners at the concert objected. The Anti-Defamation League condemned the performance in the Washington Post.

Eisenstein also described an earlier experience performing works by Ockeghem with Taruskin’s Capella Nova. “One of the Ockeghem pieces was on that very text, the Gaude Maria, and we discussed it as a group. But the upshot was that, guided by Richard, we would omit those lines.”

Another musician who performed with Taruskin from 1968 to 1978 was the distinguished scholar Lawrence Rosenwald, professor emeritus at Wellesley College and translator of many early operas and music dramas. Rosenwald described Taruskin’s performance style as “characteristically Jewish.” He calls it “extreme and over the top in the way some experiences in synagogue are over the top, that kind of out-of-body experience that you can have at the end of Neilah on Yom Kippur, or what it’s like to dance with the Torah scrolls on Simchat Torah.”

In 1992, Rosenwald published an essay, “On Prejudice and Early Music,” in Historical Performance, the Journal of Early Music America (the predecessor to this magazine). His groundbreaking essay sparked an ongoing conversation on social consciousness and antisemitic texts. This topic comes up a lot for me these days, especially regarding the antisemitic content of J.S. Bach’s St. John Passion, and I was interested in how Rosenwald’s thoughts on the topic might have evolved over the last 32 years. In his 1992 essay, Rosenwald wrote that “artistic excellence matters” and that “an argument leading to the conclusion not to perform Bach’s St. John Passion is not thinkable.”

But in our 2024 conversation, he offered a creative alternative to the extremes of either performing the piece as written or not at all: “I am considerably more arrogant as regards modifying these works than I was in the past. That is, I would rewrite the text. I would feel less timid about doing that. I would just say, ‘Come on, no, singers don’t want to sing this; I don’t want to hear them sing it.’”

‘Brought up as a Jewish person to be afraid of being Jewish.’

Violinist Jeanne Lamon directed Toronto’s Tafelmusik for 33 years and developed it into one of the world’s leading Baroque orchestras. Christina Mahler, her life partner of 43 years, recounted how Lamon’s “parents left Holland in 1939, which meant that they escaped persecution. They lost a lot of their families who didn’t leave. So Jeanne grew up with a strong sense of what happened. I mean that’s something that’s in your body, somehow more so than when it happens on a different continent.” (I could relate to the visceral experience of intergenerational trauma, affecting so many Jews around the world.)

Mahler continued, “Jeanne was brought up as a Jewish person to be afraid of being Jewish. So she really had to overcome something to start doing concerts in Germany, for example.”

Hearing Mahler’s description reminded me of being 12 and leaving my piano lesson with Robert Starer’s “Three Israeli Sketches” on top of a book of Mozart’s piano sonatas. My mother told me to put the Starer underneath the Mozart. “You don’t want to seem too Jewish,” she said. It was around the same time that my beloved Jewish piano teacher, Yvonne “Bonnie” Rosen, lent me a record of clavichord music. And the rest is history.

Byron Schenkman is a queer Jewish keyboard player and the artistic director of Sound Salon in Seattle. Their most recent recording, Art Songs of the Jewish Diaspora, with baritone Ian Pomerantz and cellist Sarah Freiberg, was released in 2024 by Acis Productions.