by Rebecca Cypess

Published February 27, 2023

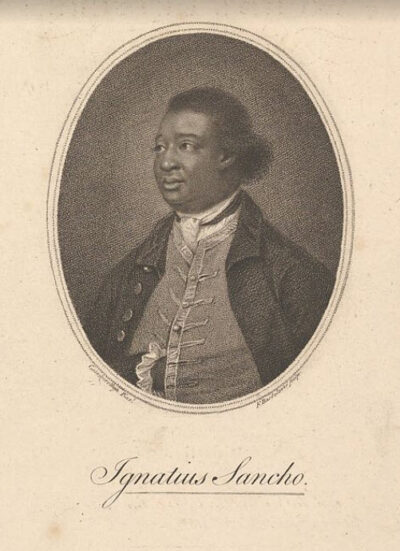

British composer Ignatius Sancho used irony and biting wit to hold a mirror up to British society, prompting reflection on its prejudice and apathy in the face of suffering.

Although Lizzo’s flute, which has a name and an Instagram account, did not make an appearance at the Grammy Awards this year, it got a shout-out when host Trevor Noah referred to Lizzo as “The most famous flute player in the world since… I’m sure there were others.” Noah, in short, placed Lizzo at the top of a tradition of musical performance—a tradition that has long included Black musicians.

Lizzo asserted her place in that tradition last fall, when she played a crystal flute built in 1813 for James Madison, a slaveholder, prompting a predictable backlash. “History is cool, y’all,” she shouted exuberantly from the stage, as she showed the capacity of music, even music without words, to convey anti-racist meaning.

Indeed, history reveals numerous precedents. Long before Lizzo, the Black British composer, writer, butler, and shopkeeper Ignatius Sancho (ca. 1729–1780) subtly but unmistakably inscribed anti-racist messages in his music.

Reportedly born into slavery and orphaned as a young boy, Sancho grew up in the London home of three sisters who denied him a formal education. By 1749, he was working for Lord Montagu, an advocate of Black social advancement through education. In the Montagu home, Sancho gained access to books and a busy cultural life. He became an accomplished writer, affiliating himself with the sentimental literary style—quirky, emotive, and fragmented—of the British novelist and preacher Laurence Sterne.

Sancho achieved fame in 1775, after the publication of his correspondence with Sterne, in which he implored Sterne to write an episode denouncing the international slave trade in his serial novel Tristram Shandy. Sancho wrote many other letters, but the majority of these were not published until 1782, after his death.

What were published during Sancho’s lifetime were his musical compositions: between 1767 and 1779, he is known to have published one book of songs and four books of instrumental dance pieces. His compositions might seem relatively modest compared to a Mozart sonata or a Haydn symphony. Yet their cultural complexity is vast.

Nowhere did Sancho write explicitly about his anti-racist approach to musical composition. He was rarely so direct. Instead, he used subtle irony and biting wit to hold a mirror up to British society, prompting reflection on its prejudice and apathy in the face of suffering.

The anti-racist messages in Sancho’s music are understated but clear. Take his treatment of the French horn, an instrument that enslaved Black people often played to accompany dancing or the hunt. Numerous advertisements demanding the return of a runaway slave noted that they could be identified by their skill on the French horn. A 1761 essay that parodies servants of all sorts claims that every white servant “has no doubt of excelling” as a violinist, while “every Black servant thinks himself qualified, by his complexion, to be an excellent performer” on the French horn. In his 1789 memoir, the Black writer Olaudah Equiano recounted that he “took great delight” in playing the horn.

While French horns were increasingly used in 18th-century orchestras, their use in dance music was generally an oral tradition; the horn parts were not often written out. In fact, I have been unable to find other examples of 18th-century dance music for small ensembles that includes horn parts. Sancho, however, includes parts for French horn in five of his minuets. This is highly significant: by writing out the horn parts, Sancho declared his affiliation with other Black musicians and documented their artistry. (Listen to one of Sancho’s minuets with horns here).

By calling attention to Black horn players in his minuets, Sancho raises a fascinating question: who would have danced to his music? His white patrons and other white purchasers of his music books would surely have done so. But there were also Black-only dances in London. In 1764, the London Chronicle described an evening “with dancing and music, consisting of violins, French horns, and other instruments at a public house in Fleet Street till four in the morning. No Whites were allowed to be present, for all the performers were Blacks.”

A year before Sancho’s death, he published his Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1779, which closes with a piece titled “Mungo’s Delight.” This is likely a reference to the character Mungo from the comic opera The Padlock (1768), by the white writer Isaac Bickerstaff and the white composer Charles Dibdin. Dibdin and Bickerstaff’s Mungo was a laughable caricature to be performed in blackface—not the first blackface character, but one that did enormous damage by mocking Black dialect and reducing Black intellect and masculinity to a joke. The name “Mungo” quickly came to used scornfully to refer to all Black men.

At the same time, Black Britons began referring to themselves as “Mungo”—a choice that may be understood as an act of reappropriation and reinterpretation. So, too, Sancho’s composition “Mungo’s Delight.” In this piece, Sancho reclaimed and reinterpreted the character, transforming him from a simpleton into a skilled, savvy musician. (Listen to “Mungo’s Delight” here.)

Sancho’s one surviving book of vocal music, his Collection of New Songs (ca. 1769), also conveys anti-racist messages. One instance is his setting of an ode by the ancient Greek poet Anacreon, whose poems had recently been published in English translation. The text seems unassuming enough: recognizing that gold cannot buy him immortality, the speaker decides that the pursuit of material wealth is unimportant. Instead, he resolves to focus on what matters: “soothing joys my life to cheer, / beauty kind and friend sincere.” Sancho’s music for the song is sweet, overwhelmingly consonant, and touching. (Listen to a performance of “Anacreon’s Ode XXIII” here.)

Looking behind this veil of consonance, however, the motivations behind Sancho’s setting of Anacreon’s poem become clearer. Anacreon’s English translator, Francis Fawkes, explained that Anacreon was part of a nation that had been conquered and sent into exile. Later, Anacreon received a gift of gold from a local tyrant, but the poet became so consumed by worry about the money that, after a few days, he returned it. The money was not worth its price in anxiety and distress.

Sancho’s correspondence tells us clearly what he thought of the mindless pursuit of money: it caused the moral stain of the international slave trade. Describing Britain’s conduct in Africa and the West Indies as “uniformly wicked,” he concludes, “the grand object of English navigators—indeed of all Christian navigators—is money—money—money.” Peel back the layers of Sancho’s song—consider his choice of Anacreon’s poem—and you find a subtle but profound declaration against the mistreatment of any human being. What matters, Sancho’s song teaches, is care for others—recognition of their humanity and their potential to be a “friend sincere.”

There were few socially acceptable ways for an 18th-century Black man to speak publicly about racism or about Black achievement. Sancho found strikingly successful ways to do so, and his music is a reminder of the Black presence in Western musical traditions. “History is cool,” indeed.

Rebecca Cypess is associate dean for academic affairs at Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University. Her work on Ignatius Sancho has been supported by the Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice at Rutgers-New Brunswick. One of her articles on the music of Ignatius Sancho was recently published by the Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies and is available freely online. With the Raritan Players, soprano Sonya Headlam, and composer Trevor Weston, she is working on a performance and recording project titled A Portrait of Ignatius Sancho: Music and Letters of an Eighteenth-Century Black Englishman.