by Christina Fuhrmann

Published January 12, 2026

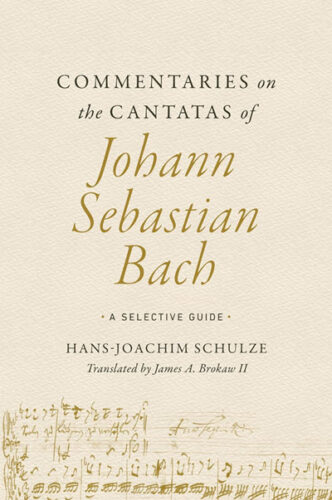

Commentaries on the Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach: A Selective Guide. Hans-Joachim Schulze, trans. James A. Brokaw II. University of Illinois Press, 2024. 280 pages.

Despite the worldwide popularity of J.S. Bach’s music, much of the influential scholarship about him remains inaccessible to a broader public because it is in German. Bach expert James A. Brokaw II has bridged this gap with several English translations of important research. Perhaps his most ambitious undertaking is Commentaries on the Cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach: A Selective Guide. Brokaw translates over 50 lectures by Hans-Joachim Schulze, one of today’s most prolific Bach scholars. An impressive online “Interactive Companion” provides translations of all of Schulze’s lectures, searchable from multiple angles.

From among Schulze’s countless studies of Bach, Brokaw wisely selected what is perhaps Schulze’s most accessible research: his radio broadcasts about Bach’s cantatas (1991–1994). These were published in German in 2006, and Brokaw — with Schulze’s blessing — has translated all of them. “Translated” has multiple meanings here, for Brokaw not only renders Schulze’s scripts into English but also provides translations for the quotations from the original cantata texts. For these, Brokaw consults not only Schulze, but also Alfred Dürr’s comprehensive The Cantatas of J.S. Bach. His English rendition is largely his own, but he does take advantage of one of the most important current Bach translation projects: Michael Marissen and Daniel R. Melamed’s BachCantataTexts.org.

Brokaw also rearranges the entries chronologically according to the latest Bach research of BWV3, divided into chapters related to Bach’s career. This is more user-friendly than Schulze’s arrangement, which primarily proceeds by the church calendar (although Brokaw’s companion website does offer that option). Brokaw has also “translated” the relatively casual lecture format, with few citations, to a more scholarly one with added footnotes. Finally, Brokaw has “translated” these talks to reflect the current state of Bach research. Brokaw, clearly an excellent scholar himself, painstakingly added footnotes and even entire supplemental sections that bring readers up to date on the latest research.

As Brokaw describes in his “Translator’s Note,” Schulze geared his talks toward the amateur listener. This primarily meant avoiding technical musical jargon and writing engagingly. Given the amount of detailed information imparted, the audience would have to be quite literate and eager for in-depth scholarly information. Schulze begins each lecture by situating the cantata in its historical context and addressing any questions surrounding its date or authorship. Entries for cantatas intended for a specific day in the liturgical calendar are prefaced by a thorough discussion of the Gospel reading for the day. As Brokaw remarks, the text of each cantata takes pride of place in these lectures. Schulze displays his encyclopedic knowledge of the poet for each text (when known), its form, and its meaning, supplemented with extensive quotations. Given that most listeners today encounter these works in concert rather than in a Lutheran service, Schulze’s rich discussion of the many religious meanings and Biblical allusions in these texts is especially welcome.

When possible, Schulze also examines the cantatas’ reception, both in Bach’s time and in later scholarly writing. Particularly amusing is his commentary on Arnold Schering’s argument that Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich BWV 150 was not by Bach. Schulze cuts through the “immoderate oratory” of Schering’s “verbal cascade” to argue for the work as an early effort by Bach. This is an especially interesting entry, since Brokaw adds an addendum highlighting later discoveries by Schulze and others, most notably that the text was an acrostic for an important figure in Mühlhausen society, “Doktor Conrad Meckbach.”

Perhaps most pitched for an amateur reader are the musical descriptions. Schulze masterfully balances a modicum of technical description with enough engaging explanation to reach a broad range of listeners. Occasionally, this results in delightfully purple prose, as in Schulze’s description of the opening movement of Ich will den Kreuzstab gerne tragen BWV 56: “the composer juxtaposes descending, heavily burdened figures ridden with sighs against a theme that struggles to remain upright with virtually herculean effort.”

Schulze’s lectures are both succinct and packed with the insights that only a lifetime of study can offer. Brokaw chose well in bringing these examples of German Bach scholarship to the English-speaking world. It is also helpful to offer readers both a printed book (“A Selective Guide”) and an expansive website (“An Interactive Companion”). Some will appreciate an approachable, self-contained book, perhaps something they might reference while listening to a particular cantata or before heading to a concert performance. Others will happily spend hours searching through the online resource, which one can approach in “four parallel series of nested paths”: by church calendar or occasion, chronologically, by the sequence of chorale cantatas, or by librettist. For those desiring a more comprehensive search tool, an entire page titled “How to Search” guides users through searching by such means as metadata field or lenses.

The website has an added benefit: When someone searches Google for a Bach cantata, a link to Schulze’s scholarship in English appears — a welcome addition (or antidote?) to AI summaries and Wikipedia entries.

Christina Fuhrmann is editor of BACH: Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute and professor of music at Baldwin Wallace Conservatory of the Performing Arts. She is the author of Opera and British Print Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, co-edited with Alison Mero, (Clemson University Press, 2023) and Foreign Opera at the London Playhouses, from Mozart to Bellini (Cambridge University Press, 2015).