by Christopher Macklin

Published March 20, 2020

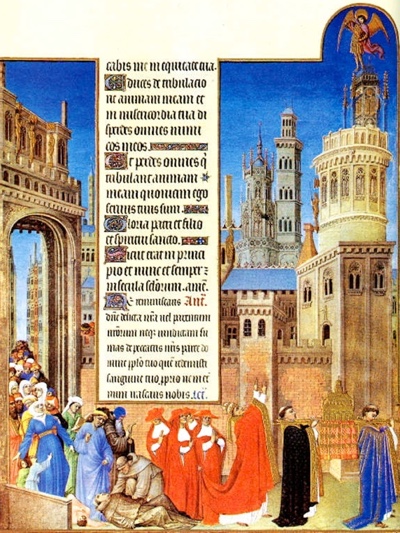

Checking the news each day with the unfolding of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is to invite feeling like we are living in times both frighteningly unprecedented and eerily familiar. Many articles have referenced the 1918 flu pandemic as a benchmark comparison for the current outbreak and even the Black Death, which for so long seemed an impossibly distant landmark of a pre-antibiotic age, has abruptly become topical. Commentators have discussed with approval how medieval quarantines foreshadow modern “social distancing” as a means of contagion control, and scented hand sanitizer and N95 face masks have supplanted the burning rushes and beak-billed plague-doctor masks sought out for protection by frightened people with means.

In the medieval and early modern period, just as now, the effect of the pandemic on artists and musicians has been severe, as moratoria on public gatherings and restrictions on travel sought to disrupt the transmission of disease by isolating the healthy as well as the sick. Indeed, one of the major distinguishing characteristics of an epidemic or pandemic, as distinct from other sickness or disease, is the way that epidemics sicken and tear at the entire fabric of the body politic, the connections and capillaries that had once nourished the far-flung members of the social body with exchanges of ideas and energy now a vector of sickness and fear.

Music is a powerful mirror for these concerns, as the dominant theoretical and theological paradigms framing the value of music in the Western tradition have long emphasized it as a physical manifestation of order and community, both of which are directly undermined by epidemics. During the Black Death, formerly harmonious arrangements of people as well as sounds became morbidly disordered and cacophonous. One of the most famous chroniclers of the epidemic, Gabriel de Mussis, described how in the face of the plague, care of social bonds were forgotten, as people ignored the “piteous voices of the sick” (vox flebilis infirmantis) even as they piteously cried for any kind of help, while after they died “no prayer, trumpet or bell summoned friends and neighbours to the funeral, nor was mass performed.” In the Tuscan community of Pistoia in May 1348, the sound of bells had ceased to evoke positive thoughts of calling the faithful to prayer and instead had become associated entirely with funerals and death, leading the municipal government to pass laws banning the ringing of bells, loud laments, and gatherings of anyone beyond the deceased’s kinfolk for mourning.

However, through more than 15 years of studying music and music-making in times of pestilence, I ultimately have been most struck by the importance of music and its power to define and maintain those capillaries of nourishing connection, far more than I have by any dirges or fears of collapse. My own research into music during the Black Death began as a macabre exercise in programming for a vocal ensemble, and, to be sure, there are musical settings that evoke the loss and uncertainty that touched countless communities as waves of plague cycled through Europe. The composer Jacob Obrecht died after contracting the plague in an epidemic raging in the city of Ferrara in the summer of 1505, where he had replaced Josquin as master of the court chapel of Ercole d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, and a setting of the Introit for the “Mass for the avoidance of death” (Missa pro mortalitate evitanda, sometimes labeled as a “Missa contra pestem” against plague) by Philippe Verdelot is based on the tenor of Obrecht’s penitential motet Parce domine.

However, such pieces are few and far between, and outside of a few corpora of motets dedicated to saints who acquired a particular reputation for healing — such as the Virgin Mary, St. Sebastian, or (later) St. Roche — there is very little of the music of the 14th through 16th centuries that is overtly “pestilential.” We may do well to consider the example of Guillaume de Machaut, who lived through the Black Death and by his own admission was powerfully affected by it: The beginning of his lengthy narrative poem (aka dit) Le Jugement du Roi de Navarre is taken up with a discussion of the devastation of the pestilence and how Machaut shut himself up in his house for months to avoid taking sick. Yet in looking at all of Machaut’s vast musical output, there is nothing providing clues (textual or otherwise) that link it to the plague’s passage.

Does this mean that Machaut spent the epidemic in fearful silence? Likely not, as he says in the prologue to his complete works that “Music is a science which asks that one laugh, and sing, and dance. It does not care for melancholy, nor for the man who is melancholy.” The avoidance of melancholy was something with direct physical relevance, as according to Galenic medical theory an overabundance of black bile led both to sadness and to illnesses such as plague, so to remain in good health, it was important to remain “sanguine” by engaging in activities that counterbalanced melancholy and promoted red blood.

Very often, music as well as other pursuits such as literature and horticulture played an important role in these regimens, as scholars like Remi Chiu and Glending Olson have elucidated in communities from the 14th through 17th centuries. Tommaso del Garbo, a 14th-century professor of medicine in Perugia and Bologna, advised his patients in his treatise Contra alla peste to:

not occupy your mind with death, passion, or anything likely to sadden or grieve you, but give your thoughts over to delightful and pleasing things. Associate with happy and carefree people and avoid all melancholy. Spend your time in your house, but not with too many people, and at your leisure in gardens with fragrant plants, vines, and willows, when they are flowering… And make use of songs and minstrelsy and other pleasurable tales without tiring yourselves out, and all the delightful things that bring anyone comfort.

Music was not a luxury in times of epidemic uncertainty, it was a necessity. Letters from the 16th-century diplomat Sebastian Giustinian indicate that when fear of the plague prompted King Henry VII to dismiss his entire court and to remain in quarantine at Windsor, the only people who remained with him were his physician, his three favorite gentlemen, and the Italian organ virtuoso Dionisio Memo. Given that Memo’s relationship to the court in other records is described purely on the basis of his musical ability, the assumption must be that he was retained in this capacity, and that, in other words, during a plague epidemic so deadly that the English court was dissolved, a musician was among the people the reigning monarch felt he could not do without.

These records have particular resonance once again in our own time, as communities across the globe have found music indispensable in negotiating a world filled with “social distancing” and imperatives to withdraw from each other. In the 17th century, the chronicler Paolo Bisciola noted that in Milan, as the numbers of cases of plague began to mount, the authorities banned the practice of singing the litanies in public “so as not to allow the congregations to provide it [the epidemic] more fuel. The orations did not stop, however, because each person stood in his house at the window or door and made them from there…Just think, in walking around Milan, one heard nothing but song, veneration of God, and supplication to the saints, such that one almost wished for these tribulations to last longer.” In the 21st century, online sharing of a recording of people under quarantine in Siena singing a folk song together from their apartments across an empty street has led to people and groups finding ever more creative ways to bring people together through music while apart, ranging from streamed “house concerts” by artists whose performances and tours have been canceled to virtual “couch choirs” allowing people to sing together with others via Skype and Zoom.

For me, one of the most powerful and evocative things about early music and its performance in the present is that it rewards the combination of scholarly rigor and artistic intuition and bravery. It asks us to view a piece of music not just with the lenses of what we were taught and of our immediate experience, but also to use our explorations of the past to imagine alternative possibilities and recognize how the smallest marking or absence of marking gives us, as artists, many more choices than we would have thought possible without the research. Performing early music mindfully is to embrace both our connection to the past and our independence from it, and to view entire generations not just of musicians, but also painters, philosophers, architects, scientists, and doctors as collaborators in making bridges among the communities we care about. And if the past is any indication, the bonds formed by using those skills will last far longer than any outbreak.

Christopher Macklin served on the faculties of Music and Medieval Studies at Mercer University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. His research focusing on music during the Black Death and times of epidemic stress has been published in journals including Early Music History and Plainsong & Medieval Music, with presentations at national and international meetings of the American Musicological Society, the Leeds International Medieval Congress (IMC), and the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, MI.