by Jeffrey Baxter

Published December 7, 2025

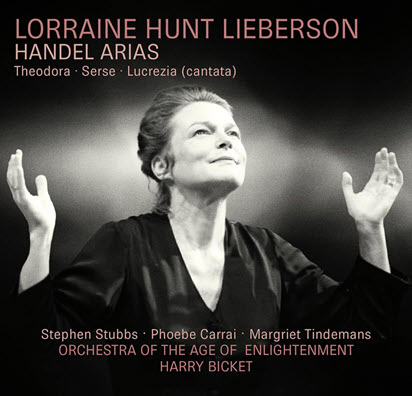

Lorraine Hunt Lieberson: Handel Arias (2025 Remaster). Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment conducted by Harry Bicket. Avie Records, AV2792

‘Artistry on another level, one that illuminates the score in ways heretofore unheard’

Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, the great American mezzo-soprano whose early demise at age 52, at the height of her career, has long left an unfillable hole in the hearts of listeners. Her Maria Callas-like commitment to character and the immediacy of her voice left a blazing impression, whether live or on recordings. Her many devotees eagerly wish to remember such incredible artistry. Hence the British Avie label has re-mastered one of her greatest albums, originally released more than two decades ago.

Hunt Lieberson’s talents in the early-music realm seemed to come naturally, first as a soprano then, later, as the burnished-toned mezzo with all the flexibility and lightness of touch to match any dramatic situation. Her career started as a professional instrumentalist — a violist with a noted facility in contemporary music – which may have been an uncommon, yet defining, component that enabled the leap to her true career: a great singer in a specialized repertoire.

While at home in music from composers of her own time — John Harbison, John Adams, or Peter Lieberson (her husband) – she made the greatest impressions in the music of the Baroque, specifically Handel. It is amazing to wonder, in a day of such specialized historical performance resources and with abundant training that’s now available, how did she do it? Is it something that vocalists can accomplish more easily than instrumentalists? Perhaps, but few have risen to the top with such unassailable credibility as this singer. The performances speak for themselves, as in this splendid recording.

Handel’s solo cantata for voice and basso continuo, La Lucrezia, dates from his early days in Rome and already shows the mastery of characterization that would come in his greatest operas and oratorios. Lucrezia’s twisting and turning melodic lines, undergirded by deceptive cadences and inventive harmonies, portray a tormented soul that one might recognize in any of the great sacred settings of J.S. Bach, whose solo cantatas BWV 82 and 189 Hunt Lieberson also sublimely performed late in life.

Conductor Harry Bicket’s colorful continuo-grouping for Lucrezia includes harpsichord and chamber organ, with Stephen Stubbs on a 10-course lute and Baroque guitar, Phoebe Carrai on Baroque cello, and Margriet Tindemans playing the viola da gamba – all providing a sensitive “orchestra” of textures and colors to support Handel’s inspired vocal writing. (In the liner notes, Bicket writes that Hunt Lieberson never lost her instrumental roots and would sometimes “bow” her arias with her hand while she was singing.)

Many moments stand out, such as the sepulchral vocal color in first movement’s frightening descent at the line, “tremende Deità del abisso” (fearful god of the abyss), the otherworldly hushed beginning of the final arioso, “Già nel seno,” where Lucretia ends her life, and the inventive and dramatically spot-on da capo ornaments in the fiery aria di vendetta, “Il suol che preme.”

The true richness of this recording – and indeed its impetus – is heard in the five arias from Handel’s 1750 oratorio Theodora. During a revival of Glyndebourne’s famous 1996 production, conductor Bicket and Hunt Lieberson agreed to create a studio recording of these pieces. Fortunately, the singer was able to manage through those 2004 sessions, although she was struggling with the beginnings of her cancer diagnosis. All the passion and beauty of those live performances is retained; in the controlled silences of a studio, an even more intimate and introspective approach was possible. On the recording, most tracks were done in a single take with minimal patching to preserve the singer’s failing energy, but the power of Hunt Lieberson’s instrument – her intense focus, breath control, and perfect intonation in the face of physical adversity – remained undiminished.

In the heart-stopping Act I aria “As with rosy steps the morn,” Bicket retains the rather slow tempo from the 1996 performances (led by William Christie). Sung by anyone else less committed to the vocal line and dramatic integrity, this almost-glacial tempo could be disastrous. Instead, Hunt Lieberson creates a timeless aura of expectancy against all hope, with her perfectly spun lines and (even Brahmsian) final cadential downward flourish.

It is a great pleasure to hear this music in this controlled setting, complete with the same intense approach – and vocal ornaments – as the staged performances. In “Lord to Thee, each night and day,” Hunt Lieberson, through some super-human force, connects the end of the B-section with the return of the A-section in one breath. This is artistry on another level, one that illuminates the score in ways heretofore unheard.

A sort-of “bonus” is the inclusion of two arias from Handel’s 1738 opera, Serse: the familiar “Ombra mai fu,” unfolded elegantly in lines of liquid legato, and the Act II aria of conflicting emotions, “Se bramante,” where allegro and adagio sections alternate in stark contrast to depict the King’s raging jealousy and deep devotion. Hunt Lieberson, who was able to turn on a dime both musically (in the virtuosic fioriture) and dramatically (in the character’s abrupt changes of heart), creates a three-dimensional portrait out of what could be mere melodrama in the hands of a lesser artist.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired choral administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – the Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, the Choral Journal, and ArtsATL. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Brahms ‘A German Requiem’ on period instruments, evoking Schütz.