by Kivie Cahn-Lipman

Published October 20, 2025

A musician partners with artificial intelligence to solve thorny textual problems

Despite more than a few negative impressions, ‘the process of exploring early-music topics with ChatGPT opened my eyes to its potential as a valuable research tool’

I have nothing against new technology. But I’ve been skeptical of artificial intelligence since its widespread emergence a few years ago. Most Google searches now result in undesired and often laughably inept AI responses. AI-generated deepfake audio and video permeate our media. Chatbots programmed to spout conspiracy theories and hate can trick the gullible and attract the deplorable. Mediocre AI research and art is taking work from skilled specialists. The environmental impact of AI is only beginning to become clear.

Nevertheless, I forced myself to explore ChatGPT the semester I taught a writing-intensive early-music history class because I wanted to prevent forbidden use of AI by learning what AI-generated papers might look like. I quickly realized that if I assigned homework requiring students to read primary and secondary sources which AI couldn’t access, it would “hallucinate” seemingly plausible but nonsensical content.

This experience solidified some of my negative impressions of the technology, but the process of exploring early-music topics with ChatGPT opened my eyes to its potential as a valuable research tool in our field — if steered by a human scholar. In subsequent conversations, it assisted me in creating a set of guidelines:

- Factual accuracy first: Always flag uncertainty; no speculation unless clearly labeled as such.

- Transparency of confidence: State whether a claim rests on primary evidence, secondary scholarship, logical inference, or pattern recognition.

- Counter-evidence check: Actively look for reasons a claim might be wrong before supporting it.

- No automatic agreement or praise: Avoid sycophancy.

These ground-rules, which it now retains throughout all our chats, seemed to significantly reduce unhelpful responses. But before trusting the AI in any areas in which I’m not expert, I tested it on several esoteric subjects in which I am.

I was impressed by its careful answers to unresolved questions regarding Bach’s piccolo cello / five-string cello / viola pomposa / viola da spalla, for which it cited real scholarly sources. I also admired its newfound willingness to admit when it had insufficient information: asked to provide shelfmarks of manuscripts in the Kroměříž Music Archive, ChatGPT acknowledged that it couldn’t, but directed me to RISM and other sources and offered correct suggestions as to how to search. (An identical query prior to establishing our guidelines had led to hallucinated incorrect shelfmarks.)

Problematic Formulations

For research, I first used AI while struggling to transcribe from manuscript the motet Mensa Sacra by Giovanni Valentini (c.1582-1649). I love Valentini’s music, and my interest in this particular piece was further piqued after learning that it hadn’t yet been published in modern edition due to the difficulty of deciphering its text.

The scribe, Benedikt Lechler (1594-1659), had sloppy handwriting and employed numerous abbreviations. Most text appears only once, even when sung by multiple voices or repeated, and the poem is unique, so snippets of Latin can’t simply be Googled. I ordered a facsimile of other Lechler copies in order to make a cipher of his handwriting using familiar texts, but while I waited I wanted to solve what I could.

The music itself was simple and contained few scribal errors, but a number of Latin words proved elusive. For context: although I have a great deal of experience transcribing 17th-century manuscripts, I’m not a musicologist or even formally trained in early music. I took barely a year of Latin in middle school — I was relocated to French after an eighth-grade spitball incident — and, being nominally Jewish with no study in this area, I have minimal understanding of Eucharistic poetry. I needed help.

I would have been thrilled to hire a human expert fluent in Latin and theology, ideally also trained in music and paleography. Unfortunately, this wasn’t a funded project; Mensa Sacra was one of many sacred works which I was vaguely considering for some future collaboration. It was the perfect opportunity to test ChatGPT’s ability to simultaneously conduct grammatical, theological, and paleographic analysis while cross-checking a trove of sources.

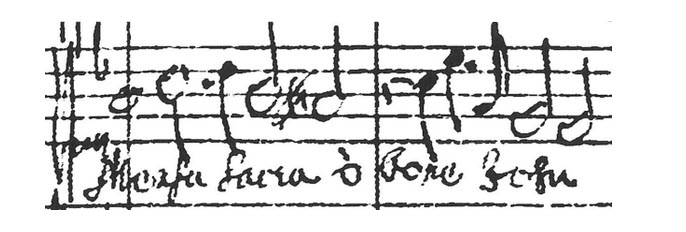

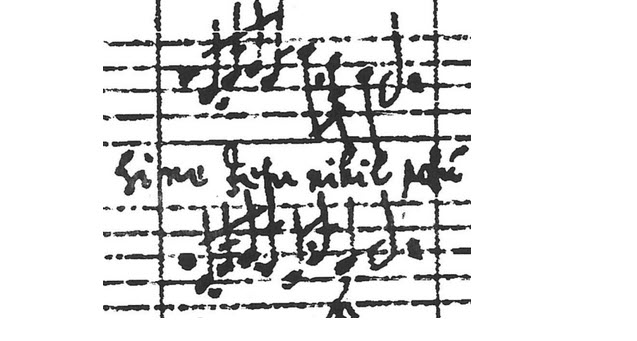

The text you see here is pixelated due to enlarging a scan of a faded manuscript. This is what ChatGPT and I had to work with. The motet’s text begins simply:

“Mensa Sacra, o bone Jesu” (Sacred table, O good Jesus). For readers curious about the musical notation, this is C1 soprano clef (although some examples below are in other clefs). What looks like an initial whole-note is Lechler’s indication of common-time, but he fit as many measures as possible between each pre-drawn barline.

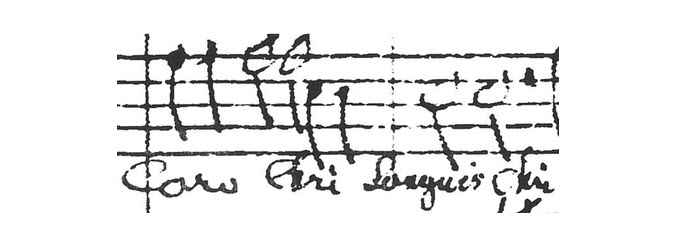

Then things become trickier. This next line looked to me like “Caro piri sanguis clai.”

“Caro” (flesh) and “sanguis” (blood) were almost certainly correct, but the others aren’t Latin words. My closest plausible transcription was “Caro pari sanguis clari” (equal flesh bright blood), which I thought could perhaps be read as “flesh, equal to bright blood.” A friend flagged this immediately as being muddled both grammatically and theologically, and it had already seemed strained visually. But we couldn’t find anything better.

I consulted ChatGPT, which agreed that “Caro pari sanguis clari” was a problematic formulation, although it then provided a lengthy and plausible justification for it. When I pushed back, it suggested I upload an image, to which it instantly responded: “Reading the letterforms (noting the common 17th-century abbreviation Chrī = Christi): ‘Caro Chri[sti], sanguis Chri[sti]’ (flesh of Christ, blood of Christ).”

This was so obvious a solution that I literally face-palmed. What I had taken as a P was simply a C with an extended swirl. In retrospect, the second “Chri” looks so clear. But I had stared at that line for a long time, and others had as well, without success.

‘This was so obvious a solution that I literally face-palmed’

However, AI ordinarily cannot solve paleographic problems by simply looking at a manuscript; often it even fails to identify which elements of the image are text. There’s a reason we’re still using Captchas — which my toddler can usually figure out — to prevent AI from impersonating humans. This was exemplified in the following line.

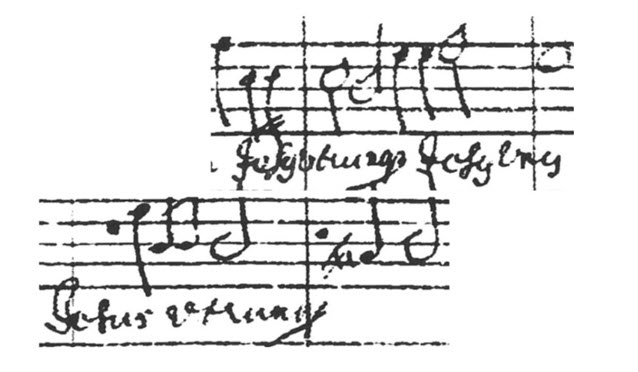

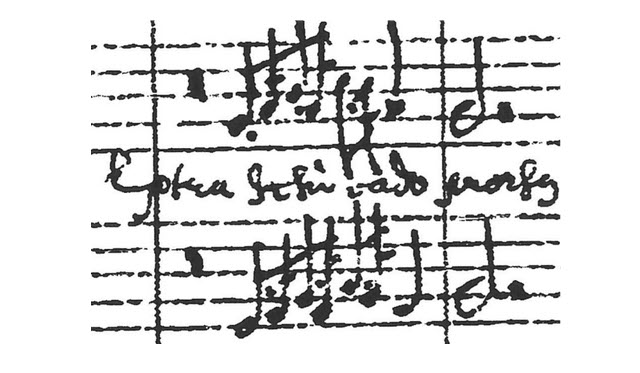

“Jesus _____” is sung in two voices, and the upper voice continues: “Jesus unus” (Jesus one). Note three instances of an antiquated -us ending in the upper staff, resembling a g with open top, and found frequently throughout this motet.

ChatGPT bizarrely misread this text as “figuratur, gustatur lingu[a/is].” After a back-and-forth, the AI recommended a new workflow: I offer all possible context and then transcribe literally what I see with no corrections, “even if nonsensical,” and it finds the best paleographic matches while cross-checking for “grammatical/semantic coherence.” As it explained:

Why this works better:

- It respects your visual advantage (you really see the ink).

- It uses my strength: eliminating impossible readings, testing plausibility, finding theologically/poetically apt fits.

I followed its advice, and I input: “This word needs to be three syllables with emphasis on the second. I clearly see a ut followed by a string of 2-4 letters (nothing ascending or descending), ending with what looks like a flourishy and sharply-leftward y, which is distinct from the normal g, q, x, and -us that this scribe uses (his common leftward-descending characters). I read one iteration of the word as ‘uturny’ and the other as ‘utruny.’”

ChatGPT’s response was a word-list ranked by probability, at the top of which was “utique” (indeed), for which it offered grammatical assurance, a theological rationalization, references to other texts containing that sequence, and an explanation that the -que ending in manuscripts often was written only as a decorated q. I quickly verified the last of these independently, and upon later examining the larger Lechler manuscript facsimile, I found that this letter was unequivocally his -que ending.

However, I didn’t believe there could be only an i between the ut- and the -que, because I twice see multiple letters and no dot. An expert friend was satisfied with “utique,” and nothing on ChatGPT’s list fit better visually.

We generated a second list consisting of the likeliest paleographic choices from my description, regardless of other considerations, and this included “utrumque” (both). ChatGPT doubted “utrumque” because it was elliptical grammatically and paradoxical contextually (“Jesus both, Jesus one”), but I noted that it was a very strong visual match followed by other ellipticals, and the paradox would be deliberate, particularly given that “Jesus both” was a duet while “Jesus one” was a solo. (I think the manuscript actually reads “utrunque,” suggested by AI — then verified by me — as an antiquated variant spelling.)

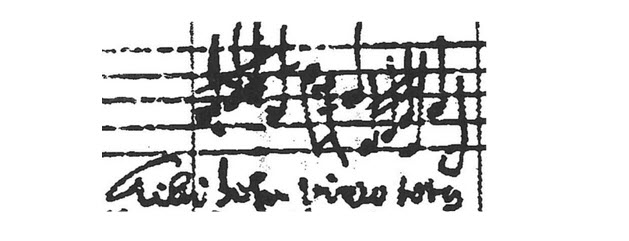

Several subsequent passages were fully legible, but a later line contained another puzzle:

“Sine Jesu nihil ___.” The mark over the u in the final word indicates abbreviation, and elsewhere in the manuscript this mostly consists of an omitted m. This word therefore seemed likeliest either “prosum” (Without Jesus I am of no use) with a compressed first syllable, or “possum” (Without Jesus I can do nothing) missing one s. ChatGPT offered a deeper search and then informed me that the latter was often spelled “posum” in early manuscripts and here “directly echoes John 15:5: sine me nihil potestis facere. This phrase is ubiquitous in Eucharistic/devotional literature. Nihil prosum is much rarer.”

“Extra Jesum ____ prorsus.” I would see “vado” or “cado,” except this is not scribe Lechler’s distinctive and otherwise consistent d (which has a strong leftward tail and does not loop back to connect to the following letter; see the penultimate word “prodeo” in the final example below). When I proscribed the d, ChatGPT read the word as “calvo” but noted mildly: “‘Totally outside the bald Jesus’ seems semantically off in devotional Latin.” It was unhappy with “vasto” (desolate) and “casto” (chaste), our two best options without a d.

But ChatGPT pushed back and recommended the d. It wrote that “cado” (Outside of Jesus I totally fall), “feels more natural.” Pressed on what “feeling more natural” meant to an AI, it responded: “‘Cado’ presents a very common spiritual metaphor (cf. Augustine, penitential texts). It is more theologically, poetically, and idiomatically compelling, even if ‘vado’ might be visually possible.” I kept “cado,” confident that it was grammatically and contextually sound, although I remained unconvinced paleographically until later finding several similar ds in other Lechler manuscripts.

ChatGPT pushed back, arguing it ‘feels more natural.’

Skipping to the end of the motet:

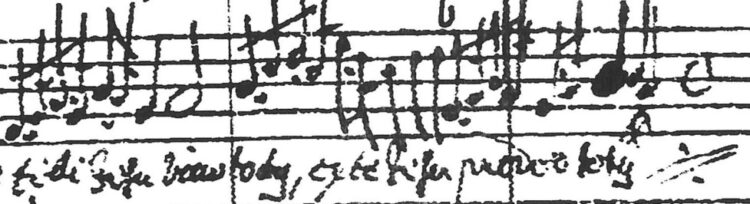

“Tibi, Jesu, vireo totus” (For you, Jesus, I flourish wholly).

“Tibi, Jesu, vivus totus; Ex te, Jesu, prodeo totus” (For you, Jesus, I am entirely alive; From you, Jesus, I go forth completely). The symbol at the end indicates to repeat the previous text.

I struggled with a few words in these lines, and ChatGPT badly misread each from the images. But when I described their appearances the AI corrected to the text above. The poem ends simply with “Jesu, Jesu, Jesu, Jesu,” in pp followed by ppp, an idiomatic Valentini signature in dynamics that would be otherwise anomalous in the 17th century.

In a later conversation, I asked ChatGPT to analyze the completed draft poem for plausibility without taking into account anything we’d discussed in reconstructing it. It flagged “vireo” as theologically unusual, but after further analysis that remained our best option.

Unless a concordant copy of this poem appears in a cleaner hand, “best options” are all I can hope for. This kind of reconstruction rarely yields certainties, but AI has helped me reach closer to the composer’s intentions than would have been possible on my own, perhaps matching or even surpassing what a true expert might have achieved. I would be thrilled to be proven wrong: if a scholar accepts my title’s challenge and demonstrates conclusively that ChatGPT and I erred on some of these words, the happy result will be performances and recordings which are even nearer to what Valentini wrote.

Ultimately, my goal (and probably that of most academics) is acquiring knowledge — seeking truth. I remain troubled by the myriad ethical quandaries of AI, but I also believe that it is a tool which can help us reach truths that would be otherwise unattainable.

Kivie Cahn-Lipman is the founder of Baroque string band ACRONYM and Scottish galant ensemble Makaris, and co-founder of viol consorts LeStrange and Science Ficta. He is associate professor of cello at Lawrence University.