by Anne E. Johnson

Published August 1, 2022

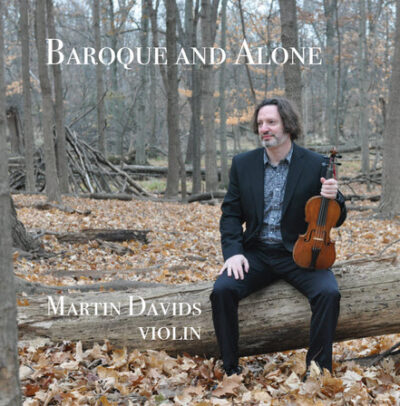

Baroque and Alone. Martin Davids, violin. Self-released.

Martin Davids has created unaccompanied Baroque violin suites where there were none. His new CD, Baroque and Alone, was a pandemic project and a very personal one. While multiple quarantined colleagues focused on the Bach solo sonatas, he wanted to carve his own one-fiddle path, even if he had to dig it himself. That meant newly assembled pastiches, a completely original work inspired by the Baroque, and the premiere recordings of two 18th-century pieces. It is, to a degree, a successful experiment.

In the liner notes, Davids justifies the project: “As much as I love and respect many composers, I sometimes find I don’t love every movement of their sonatas.” So he glued together movements he liked from multiple composers, organized by key and tempo rather than dance type. Not the most Baroque approach. Then again, even purists must admit that pastiche itself is a sublimely Baroque construct.

What Davids calls Suite No. 1 in B-flat Major combines a prelude by Johann Christian Pepusch, an allegro from Georg Philipp Telemann’s Fantasy No. 1, and a theme (based on Rameau) with two variations from Variations on Les Sauvages, a never-before-recorded work by Joseph-Barnabé Saint-Sevin, known as L’Abbé le fils (1727-1803), familiar to early-music scholars for his book on violin pedagogy.

Now playing a 1750 Ferdinando Alberti violin, Davids was a student of Stanley Ritchie’s at Indiana and is a strong presence in early-music ensembles around the country. In these pieces, he seems determined to erase all thought of dancing from the movements he’s collected. While the Pepusch Prelude is appropriately stretchy, so is the Telemann Allegro, rather than providing a contrast of metrical tightness. The Allegro does, however, grow naturally out of the prelude’s material, so it fits well.

Intriguing and tricky, the Saint-Sevin demands delicate string crossings, quick left-hand shifts, and intricate double stops. Davids’ rhythmic looseness knocks the legs out of the syncopation that the composer carefully provided. These theme and variations are stylistically so different from the Pepusch and Telemann movements that it’s hard to understand why Davids combined them.

Davids’ own Chaconne, using techniques borrowed from Baroque literature, is skillfully wrought, a retrospective exercise inspired by love for the era. The other premiere recording here is Fantasia pour un violon seule (1723) from the second volume of sonatas by British violinist and composer Henry Eccles. The three-movement work, distinct from other movements on this recording for its tonal simplicity, is a nice find but hardly a hidden gem.

In the pastiche titled Suite No. 2 in G Major, Davids intersperses movements by Nicola Matteis (fl.1670-1730) with those of the more widely known Giuseppe Tartini. Tartini then swaps licks with Telemann in Suite No. 3. In Suite No. 4, the most coherent of the pastiches, it’s Matteis and Tartini again with a surprise visit from J.S. Bach for the finale. The first movement by Mattheis, marked Passagio rotto, andamento veloce, is a particularly engrossing journey through implied polyphony, preparing the ear for the Bach to come (from his A minor Sonata, BWV 1003). The Tartini Adagio second movement uses a repeated motif of minor-second double stops that’s worth the price of admission.

The violin’s rich, warm sound does not smooth away the high frequencies of normal bow-to-string friction, which is so important to a natural sonic presentation. Producer Julia Davids and engineer Mary Mazurek keep the instrument focused and without echo, despite it being recorded in a church; that clarity helps in moments of metrical uncertainty.

All the pastiches are fun, and some movements are eye-openers. However, with the exception of Suite No. 4, it’s hard to know if Davids’ home-made concoctions will have a life beyond being a pleasant way to pass pandemic time.

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. Her arts journalism has appeared in The New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and Copper: The Journal of Music and Audio. For many years she taught music history and theory in the Extension Division of Mannes School of Music.

More CD Reviews:

No posts