by Anne E. Johnson

Published October 13, 2025

“Where’s the little heir of this house?” said long Lankin.

“He’s asleep in his cradle,” said the false nurse to him.

“We’ll prick him, we’ll prick him all over with a pin,

And that’ll make my lady to come down to him.”

So he pricked him, he pricked him all over with a pin,

And the nurse held the basin for the blood to flow in.

This gruesome verse comes from a song called “Long Lankin.”

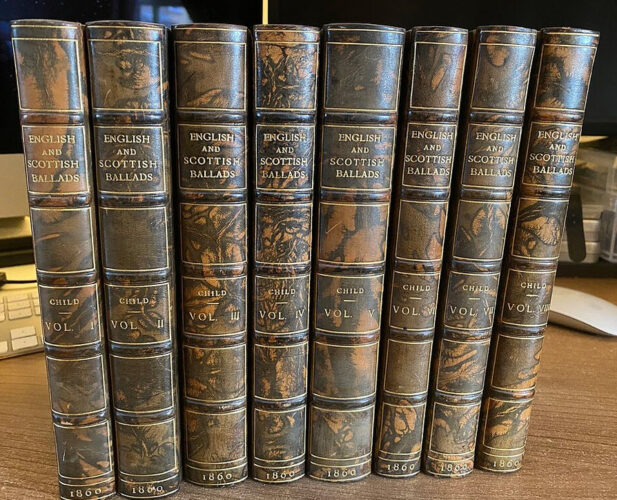

“Long Lankin” is song No. 93 in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads by pioneering American folklorist Francis James Child (1825-1896). That collection, which first appeared in 1860, still influences the fields of folklore and ethnomusicology, not to mention folk music performance. And as the early-music community increasingly opens its ears to traditional music, this might be the perfect moment to spread the word about Child’s remarkable project.

The 200th birthday of Child, the first president of the American Folklore Society, will be celebrated by the AFS at its annual conference this year. The in-person segment meets in Atlanta Oct. 18-21, followed by an online portion Nov. 12-14. Overall, the conference’s theme, “Restoring and ReStorying,” dovetails with Child’s legacy, says scholar Michael J. Bell, the representative of the AFS’s History and Folklore Section who spearheaded the tribute.

“We didn’t ask for 28 people to come and deliver a paper on Francis James Child,” Bell explains. Instead, the organizers wanted to “ensure that the society had an opportunity to acknowledge Child as a founding parent of folk studies in America, but also to make the case for reviving and recalling attention to the work being done in folk song and ballad.”

Folk revivals ‘find an essence of identity against the commodification of culture,’ protesting how ‘everything can be sold.‘

Bell sees the Child Ballads as one of the founding pillars of folk studies, the other being Grimms’ Fairy Tales. “They created great studies of folk narrative and great studies of folk music,” he says. “However, that changed over the 20th century as it became harder to find communities in which traditional oral singing was preserved because media and modernity invaded everywhere.”

As to why the ballads that Child collected have captured Bell’s attention for his whole career, “I am deeply moved by the emotion created by their telling a story. They’re beautiful. If you listen carefully, they can create moments of sheer awe in terms of how the poetry works.”

The key word there is listen. These days, folk music is normally studied as something one only hears. “In the 20th century, folk songs began slowly to be recorded,” says Bell. With this change, “we became much more interested in finding singers and recording singers. We became as much interested in the context of song performance as the song itself.”

That modern approach was far from Child’s purpose. At Harvard, he was a professor of rhetoric and oratory specializing in English poetry, not a musicologist. Bell says Child invented the genre name “popular ballad,” viewing it purely as a form of poetry. And although many of the 305 songs in the collection are presented in multiple versions, this was not the result of ethnomusicological field work. He acquired notation for only a small percentage of the songs. And his main sources were previously published books, not aged singers in remote villages in the Hebrides.

The ballad tradition “was experienced as poetry because the earliest collectors couldn’t write down tunes,” says Bell. Eventually every song would be paired with one or more melodies, primarily through the work of American scholars Phillips Barry and Bertrand Bronson.

In the Romantic era, “ballads were seen as evidence of the foundational features of national identity,” says Bell. They were proof “of the soul of the people, a thing that bound tribes and — I use the word in the old-fashioned sense — bound races together.” Echoes of this view of ballads remained in the 20th century, when “we started talking about ethnicity in the modern sense of identity. They became part of each culture’s identity.”

Bell sees the folk revivals in the U.S. and Britain as a way “to find an essence of identity against the commodification of culture,” protesting how “everything can be sold. ‘Folk’ feels to be something that cannot be owned yet belongs to all of the people.” That attitude in the revivals of the 1940s through ’60s made the Child Ballads a perennially important resource. “But it’s only very recently that those who played the music became the scholars of the music,” Bell points out.

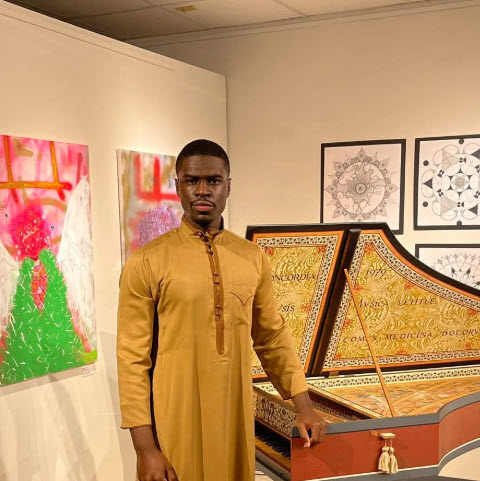

At the AFS conference, one such singer-scholar is Joseph Makoviecki, a folksinger, writer, and sound artist from the Pine Barrens of New Jersey. His paper, “Pine Barrens Variants of Child Ballads,” compares Child’s work with that of Herbert Halpert, who in 1938 published a collection of 40 ballads from the Pine Barrens, comparing each “with the Child version it most resembles,” Makoviecki explains. He hopes to tell “a more complete story about where Child ballads were remembered and were sung in America.” You can hear Makoviecki’s band, Jackson Pines, singing one of those songs on YouTube:

Makoviecki’s work illustrates how the source ballads that Child collected had traveled and changed as part of the oral tradition. They went “anywhere the English language went with British imperialism,” says Bell, including “Australia, New Zealand, South Africa.” And, of course, America. Child also mentions some song versions in Scandinavian and Germanic languages. “There were always people traveling from country to country. If you’re living in a world where you show up in a new town and you want to get business, you maybe start by going to a pub and telling a story or singing a song.”

Modernization broke down that means of communication. The people learning to sing Child ballads in the 1960s — for example, Joan Baez, Oscar Brand, and John-Jacob Niles in America; Ewan MacColl and A.L. Lloyd in Britain — did not learn them at their mother’s knee or from a traveling merchant in a pub. They learned them from published collections like Child’s. (Niles was to create his own important collection of American traditional songs.)

It’s not just that culture has changed — so has the scholarly attitude toward studying it. “Most folklore scholarship in the early years operated from an idea that folk culture was fast disappearing,” says Bell. “We spent an enormous amount of time making sure stuff did not get lost, and we shifted to paying more attention to how people performed folk song, where they did it, what it meant in their lives at that moment.”

Moving Beyond Child’s Approach

The shift in where attention is paid is a major factor in how papers were chosen for the AFS conference. Eleanor Rodes is a young scholar who graduated from Swathmore in 2025 with a BA in Music, Oral Narrative and Social Context. She is presenting a paper called “The Role of Contextualization in Folksong Scholarship,” dealing with “the importance of fieldwork which fully respects, embraces, and preserves in community not only the narrative material itself but also its fuller cultural context.” Such thoughts would likely never have crossed Child’s mind.

By acknowledging Child’s importance in preserving “hundreds of ballads and variants which may have otherwise been lost,” Rodes celebrates the developments built on his foundations. She highlights three such developments: representation from more diverse voices, active engagement from members of the community being studied, and a commitment to keeping the traditions alive in their communities as well as simply preserving them.

Another presenter is John H. McDowell, a professor emeritus at Indiana University, who looks at narrative song as a way of constructing history, specifically “the corridos (ballads) produced by Afromestizo populations of Mexico’s Pacific Coast.” Although McDowell shines a light on the popular ballads of a different demographic from the one that interested Child, there’s an important parallel: “My focus on the lyrical in lyrical narrative takes its inspiration from a figure who in some ways is Spain’s counterpart to Francis James Child, namely Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869-1968).”

If the field of folksong scholarship has moved so far beyond Child, one might reasonably ask whether he should be the subject of a bicentennial celebration. Hilary Warner-Evans, who earned her doctorate in 2025 from IU’s Department of Folklore and Ethnomusicology, leads the AMF’s Music and Song Section and thus has been heavily involved in putting the conference together. She feels that Child continues to be relevant because his work “served as a fundamental basis for generations of folksong scholars and collectors who came after him.” He also was instrumental “in the institutionalization of folklore as an academic discipline in North America.”

So, where do early-music aficionados figure into Child’s legacy? Well, for one thing, some of the songs are very old. Child included 38 different ballads about Robin Hood, for example, and some of those have medieval roots. And the categories of “composed” versus “traditional” have long been intertwined. “The jongleurs — are they popular performers?” asks Bell. “They’re living in a world where they’re moving back and forth between the music they hear around themselves and the music they produce for their audiences.”

Ballads are also windows into past society. Bell argues that “folk music had extraordinary influence not only on how people thought about the world of sound that they lived in, but how composers invented that world of sound.”

There are abundant online resources to explore Child’s collection, including archived materials and blog posts from the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress. You can easily from explore a complete set of Child’s published works.

Anne E. Johnson is EMA Books Editor and frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently wrote about Amherst Early Music’s revival of Georg Reutter’s ‘Dafne.’