by Andrew J. Sammut

Published January 29, 2026

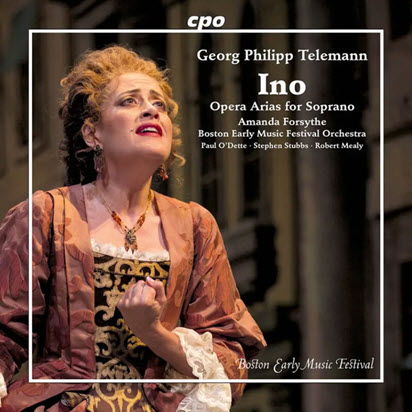

Telemann: Ino and Opera Arias for Soprano. Amanda Forsythe, Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra, directed by Robert Mealy, Paul O’Dette, and Stephen Stubbs. CPO 555658-2.

Forsythe’s simmering delivery adds up to one of the sultriest moments in Baroque opera

Georg Philipp Telemann composed about 3,000 works, setting a world record and inviting jokes about quantity over quality. Not long ago, some scholars seemed to trash him just to elevate J.S. Bach — whom Telemann respected as a colleague, a close friend, and father of his godchild, Carl Philipp Emanuel. Nowadays, Telemann’s reputation as an also-ran, a journeyman, “fine-but-he’s-no-X” creator gets welcome push back.

Musicians continue plumbing Telemann’s massive catalog, encompassing everything from solo instrumental pieces to multilingual operas. The Boston Early Music Festival’s Telemann: Ino and Opera Arias for Soprano explores some of his dramatic vocal works, spanning from his years as Leipzig opera director, at age 21, through two years before his death at 86, when he composed Ino (1765), a 35-minute, German-language cantata.

Telemann was a late-Baroque composer who appreciated both old-fashioned and brand-new music. As Steven Zohn’s excellent liner notes discuss, the elderly composer took an innovative approach to the cantata form with accompanied recitatives, through-composed arias, greater alignment between music and libretto, and touches of the developing Classical style — a parallel with the operatic reforms in the 1750s and ’60s codified by Gluck.

Ino depicts the title character fleeing with her son from her husband’s murderous rampage. Based on a myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, there are trysts with gods, acts of divine vengeance, and the protagonist’s apotheosis into an ocean deity. Through Telemann’s score, Karl Wilhelm Ramler’s text, and the musicians’ sensitivity, the fantastic setting becomes a compelling, grounded dramatic scene: A terrified human being escapes violence while trying to protect her son and barely containing rage at powers beyond her control.

A descending bass line amplifies Ino’s cries for mercy from the gods, turning this brief moment of dry recitative into an event. When, out of desperation, Ino plunges into the sea with her son, a suspenseful harmonic progression choreographs her fall, her struggle in the water, and her search for the child. Repeated notes and plush textures then choreograph her staying afloat and relief when they’re both rescued.

Amanda Forsythe, one of the great sopranos of our time, captures the wide range of emotions packed into this 11-movement cantata with dramatic conviction and a silvery yet warm soprano, packed with a range of colors and clear, full high notes. She shapes the name “Saturnia” with a subtle rhythmic push, spitting the name of her divine nemesis out in anger. Expressing Ino’s terror as she flees from her husband, Forsythe conveys physical and emotional exhaustion with subtle vibrato and sculpted phrase endings.

The soprano has a strong collaborator in the BEMF Orchestra under the direction of violinist Robert Mealy and musical directors Paul O’Dette, on archlute, and Stephen Stubbs, on Baroque guitar. Two instrumentals from Telemann’s orchestral suites bookend the disc, showing off the group’s rich sound and impressive balance. The first overture is particularly vivid with its concertante flutes and bassoon. The instrumentalists also feel the dance roots of this music. Their rhythm is crisp and cohesive, catching the lilt of the sea creatures’ festivities and the momentum of Ino’s outcries.

Excerpts from Telemann’s operas fill out the disc. They’re all inventive and performed with nuance. A few stand out, if by a hair. In “Rimembranza crudel,” from Germanicus (1703), Agrippina watches her husband leave for battle, lamenting in long, pained lines between dense orchestral strands. Forsythe’s vocal control and pinpoint dynamics create an uncanny chiaroscuro effect. Her lines emerge gradually from the contrapuntal texture for an air of noble tragedy.

“Erscheine bald,” from Emma und Eginhard (1728), is another standout. Charlemagne’s daughter loves a servant despite her father forbidding class-crossing romances. A lyric like “come soon, you seducer of my sense” and the angular, chromatic lines careening in unexpected directions, plus Forsythe’s simmering delivery add up to one of the sultriest moments in Baroque opera. “Mischt, ihr muntern Nachtigallen” (Flavius Bertaridus, 1729) features lovely duet and trio writing for two sopranino recorders and voice.

Given the outstanding musicianship and insightful program, it’s no surprise this disc won the 2025 Grammy Award for the Best Classical Solo Vocal Album category.

Andrew J. Sammut covers music for Early Music America, The Syncopated Times, Vintage Jazz Mart, and his blog, The Pop of Yestercentury. He has also written for All About Jazz, Boston Classical Review, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.