by Aaron Keebaugh

Published October 16, 2025

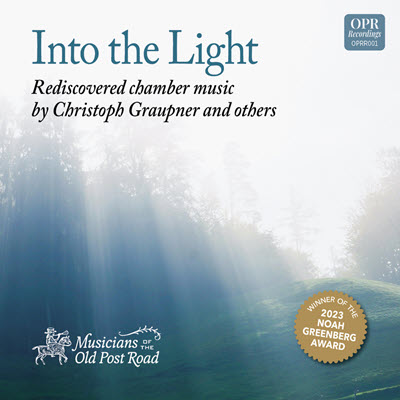

Into the Light: Music by Graupner, Telemann, Fasch, and Louis. Musicians of the Old Post Road. OPR Recordings OPRR001

The music of Christoph Graupner was held in such esteem that Leipzig dignitaries offered the composer the role of cantor of the St. Thomas Church. Though he passed on the position, just as Telemann had, Graupner’s top candidacy for even a provincial job revealed his international renown. He had seemingly done it all, composing operas for Hamburg and a plethora of choral and chamber music for the court of Darmstadt, where he spent most of his career.

Yet by the time of his death in 1760, Graupner’s style was considerably passe. Thirst for new styles were so pervasive that the library in Cöthen removed his works along with those of his contemporaries from their catalogue. And while J.S. Bach and Handel have been restored to the musical pantheon, Graupner’s legacy has largely remained buried in time. Only in the last several decades have new recordings thrust his name back into the spotlight.

It is in that spirit that Boston’s Musicians of Old Post Road explore Graupner’s legacy in their latest recording, Into the Light. This recording of rediscovered chamber works — the first on the ensemble’s own label — is so vividly shaped and shot through with energy that the composer’s unique play of rhythm, texture, and harmony remain difficult to ignore. When heard alongside pieces of his both better and lesser-known contemporaries, Graupner’s star feels restored to its rightful place.

The sonatas and concertos contained on this disc are cast in a style that owes as much to Corelli as to north German seriousness. Graupner fully embraced the Italian style, but with a twist: his melodies sing brightly even as his harmonies routinely explore dark corners.

Graupner’s Trio Sonata in B minor leans into these extremes. Flute and violin work together instead of against each other. But Benjamin Katz’s harpsichord interrupts the lines with stinging dissonances that generate live-wire intensity. The effect reverses course in the second movement, where rippling arpeggios and sustained bass notes provide the frame on which the solo instruments hang their melodies. Graupner’s music is at once a venue for conflict and compromise.

That’s even true of Graupner’s Sonata in G Major for flute, obbligato harpsichord, and continuo. The freedom the musicians bring to the opening movement suggests congenial immediacy. Yet even here shadows enter the fray — dark chords tether the melodic flights of fancy securely to the earth. The emotional turbulence also offsets any sense of resolution in the second movement, where the music broods quietly. Here, too, Graupner’s music turns quickly on a dime. The final movement is playful and effervescent, as if the previous tension had been all for naught.

But even when Graupner keeps his music in the chromatic fog, the energy of each line burns fervently. His Quartet in G minor for strings and continuo unfolds from the spare opening to silvery resonance. The musicians treat the buildup with real Baroque fire.

They do the same with Graupner’s Concerto in D Major. Flutist Suzanne Stumpf tears through the melodic thickets with athletic ease. Again, contrasts emerge just as suddenly. In the Largo, Stumpf’s line blends with string players Sarah Daring, Jesse Irons, Marcia Cassidy, and Daniel Ryan like chocolate and strawberries, the sound sweet yet biting. This is music to savor, and the musicians make each moment count.

The other pieces on Into the Light complement Graupner’s wayward tensions. Johann Friedrich Fasch’s Sonata à Quattro in G Major searches for, and eventually finds, resolution. But there’s plenty of musical adventure along the way. Flute and violin play with spirited elan before the emotions suddenly run into the thickets. Stumpf’s flute is capable of sheer grit as smooth solace. The spirited finale, crisply played, courses like an electric shock.

Ernest Louis’s Chaconne in A Major for strings and continuo provides supple counterweight. Louis, the Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt, was Graupner’s patron and a composer in his own right. His Chaconne shows a hand with a firm balance for sensitivity and flair. The musicians treat this music to a gentle flow that allows for the phrases to lift.

They do the same in Telemann’s Quartet in D minor, which balances melancholy with sly wit. The opening movement bubbles in a slow boil but gives way to a serene Adagio and lively finale. As before, the music plays upon darkness and dynamism. It may be Telemann at his best, but it’s also as Graupnerian as one can get.

Aaron Keebaugh’s work has been featured in The Musical Times, Corymbus, The Classical Review, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, BBC Radio 3, and The Arts Fuse, for which he serves as a regular Boston critic.