by Andrew J. Sammut

Published February 6, 2026

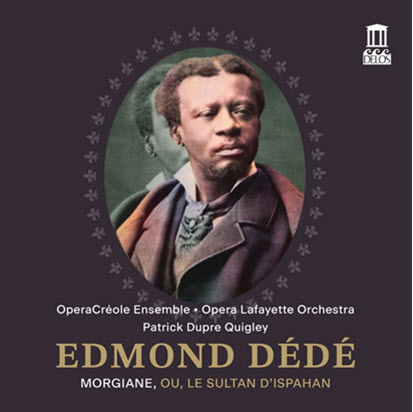

Dédé: Morgiane, ou Le sultan d’Ispahan. Opera Lafayette Orchestra, OperaCréole Ensemble, and soloists conducted by Patrick Dupre Quigley. Delos DE3628

Rich string writing, a variety of obbligato parts, and snappy dance rhythms point to a composer with an ear for both formal and folk traditions

The cultural significance of this project is obvious: Morgiane is the oldest surviving opera by a Black American. Edmond Dédé completed his magnum opus in 1887 yet never saw it performed. In fact, no one heard Morgiane until 2025. Dédé (1827-1901) was a free person of color born in New Orleans who relocated to France to escape the racist systems that restricted his musical aspirations and violated basic human dignity.

In an excellent article for EMA, Patrick D. McCoy outlines the composer’s extraordinary life and the enormous effort to finally stage Morgiane, ou Le Sultan d’Ispahan. Now the opera’s first-ever recording has been released, taken from a live performance less than a week after its world premiere.

Morgiane was Dédé’s only opera, which he revised throughout his career as a respected conductor, composer, and violin soloist. The score reflects his clear affection for the story and creative breadth. The composer’s music-hall experience shows in brief, catchy melodies and smooth harmonies. The chorus’ participation in the drama and the lush orchestration show his love of French grand opera. Rich string writing, a variety of obbligato parts, and snappy dance rhythms point to a composer with an ear for both formal and folk traditions.

The libretto, by Louis Brunet, reworks characters and themes from “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” into a tragicomic story of young love, familial bonds, sexual tyranny, and mysterious parentage. The Persian sultan, Kourouschah, kidnaps young Amine on her wedding day and demands she marry him instead. Her mother Morgiane, father Hagi Hassan, and fiancé Ali disguise themselves as itinerant musicians and attempt a rescue. They’re soon discovered and sentenced to execution — until Morgiane reveals that Amine is, in fact, Kourouschah’s daughter, born shortly after the then-sultaness fled his court. Kourouschah releases everyone, the youngsters wed, and all is forgiven.

Dédé’s musical characterization nails the libretto’s darkly humorous tone. Morgiane plots to rescue Amine in a static vocal line over cool, dark harmonies. She’s the level head against her husband’s agitated phrases. Their daughter is no helpless captive: high notes and flashy runs convey Amine’s outrage in the face of her captors. Much of the solo vocal writing is in the declamatory French style. This lets the sporadic arioso moments add variety and dramatic interest, such as when Hagi Hassan implores the merchant camp for shelter.

The orchestra adds atmosphere and depth to the characters across four through-composed acts. A sweet, fragile accompaniment uncovers Amine’s plaintive side when she asks about her true parentage. Chromatic winds beside Kourouschah’s declaration of love to Amine hint at a lonely sultan, but when he proclaims that she will be his wife, the brass section reveal a tyrant’s certainty.

The chorus comments on and responds to the action throughout: celebrating the young lovers, portraying a bustling marketplace, consigning the failed rescuers to the dungeon, and cursing the sultan in tense, suspension-filled imitations between choirs.

The recording comes from a live performance at the University of Maryland’s Dekelboum Concert Hall. The ensemble displays obvious emotional commitment to this unearthed music and quirky tale. No single voice draws too much attention. Instead, there’s a sense of collective responsibility to let Dédé’s music get the spotlight.

Nicole Cabell’s fiery soprano underscores the narrative purpose of Amine’s virtuosic displays. Soprano Mary Elizabeth Williams gives the titular character — who has carried so many secrets for so long — a dignified presence. She’s particularly compelling in Morgiane’s origin story, both lyrical and lively singing about galloping horses and ferocious tigers. As Hagi Hassan, Joshua Conyers plays fatherly, vengeful, coy, and flustered with a big, warm baritone. Playing Ali, Chauncey Packer’s bright tenor convinces as a youth caught between love for his fiancée and rage at her captors.

Kourouschah is a tyrant with some soft edges, and bass Kenneth Kellogg’s dynamics and inflections catch that nuance. As Beher, bass-baritone Jonathan Woody captures the sycophancy and bullying of the sultan’s majordomo. When Beher comments on Amine’s beauty and orders Hagi Hassan to surrender her in the same breath, it’s a downright oily scene, especially with the orchestra’s ominous accompaniment.

It’s easy to appreciate Dédé’s big effects and subtle details through conductor Patrick Dupre Quigley’s direction. His pacing gives the words and rhythms space to make an impact. Both the Opera Lafayette Orchestra and OperaCréole Ensemble chorus dig into Dédé’s score with enthusiasm, balance, and transparency. Quigley, OperaCréole co-founder and artistic director Givonna Joseph, and everyone involved have a lot to be proud of, for delivering a stirring opera, and for reviving an essential artist of American musical history.

Andrew J. Sammut has covered music for All About Jazz, the Boston Musical Intelligencer, the Syncopated Times, Vintage Jazz Mart, and his blog, The Pop of Yestercentury. A regular EMA contributor, he’s written about Makaris and the mysteriously gallant David Rizzo.