by Gwyn Roberts

Published September 8, 2025

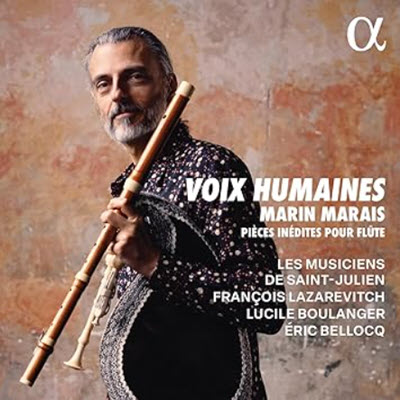

Voix Humaines: Marin Marais Pièces inédites pour flûte, Les Musiciens de Saint-Julien, ALPHA 1126

This new recording represents the unboxing of one of the most significant discoveries of Baroque flute music in recent history: a large trove of music designated specifically for flute and continuo by one of the most important composers of early 18th-century France, Marin Marais. A viola da gamba virtuoso, Marais wrote nearly all his chamber music for his own instrument, although he did include flute among the list of instruments that could adapt some of those works for their own use. The pièces on this recording come from volumes acquired at auction in 2023 by American flutist Michael Lynn, detailed in his EMA article “Champagne Flutes.”

The recording ensemble, Les Musiciens de Saint-Julien — François Lazarevitch playing flute and musette; Lucile Boulanger, viola da gamba; and Éric Bellocq, archlute and guitar — is among France’s finest, active in both Baroque and folk music.

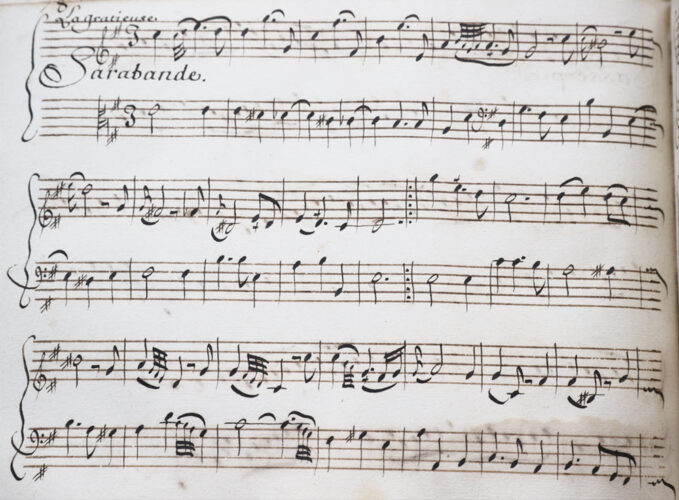

The 120 pages of movements by Marais that include most of this recording’s repertoire are beautifully copied in what looks like a professional hand. They are bound together with other published works for flute from the same period by composers whom Marais knew personally: Hotteterre, La Barre, and Gauthier.

While it is not unusual for such manuscript sources to contain questionable attributions, the inclusion of three movements that have concordances in Marais’ known gamba works bolsters the idea that these pièces are indeed by Marais. So does their exceptionally high quality and stylistic language. And, in an odd way, so does the fact that they appear not to have been written by a flutist: François Lazarevitch’s liner notes mention that some of the phrases are just too long and difficult to be played in a single breath and appear to be by a composer who “thinks and writes for the bow.”

The main manuscript is disorganized, with movements in various keys and in various forms jumbled together, leaving it to the performers to pick and choose sets for themselves. For this recording, Lazarevitch and his team have assembled two main suites from it and filled out the recording with other individual movements and two additional suites, some from other manuscripts and some transcribed anew from Marais’ published gamba works. We hear Voix Humaines, the title track, twice: in the famous piece from Marais’ Second Book for viol and, with completely different music, in the recently discovered work for flute and bass.

The recording itself is beautiful and highly individual, and the flute and the continuo team are well-recorded in an attractive acoustic. The sound picture is varied by the inclusion of one suite that Lazarevitch performs on muzette, as well as some individual movements featuring the guitar and viola da gamba as soloists themselves. I find the sarabandes to be especially beautiful. If the manuscript and recording had yielded us only those as new movements, the discovery would still have been significant. According to the liner notes, the movements and suites drawn from sources other than the main Marais manuscript have needed reconstruction of their bass parts and/or transcription to fit on the flute, all of which has been stylishly done.

What stands out to me as a listener, besides the compelling and virtuosic playing of all three musicians, is how very highly ornamented the performance is. A glance at the manuscript (courtesy Michael Lynn) reveals a rather high amount of written-out ornamentation for music of this period, especially in the slow movements. Lazarevitch has then added a lot of ornamentation of his own. As a musician who performs and records both notated art music and folk music in a variety of styles, he has developed a very individual musical voice, suggesting that there is at least as much for us to learn from oral traditions as there is from treatises. He brings this distinct flavor and an immense imagination to this recording. The results are both unique and compelling — there’s not another musician who would have performed these pièces in this exact manner.

Musicians who want to explore this extraordinary treasure chest of early works for traverso themselves can order an edition prepared by Michael Lynn for ALRY Publications, and a digitized copy of the manuscript itself will soon be available through the Library of Congress.

Gwyn Roberts is professor of recorder and Baroque flute at the Peabody Conservatory and directs Baroque ensembles at the University of Pennsylvania. She is founding co-director of Philadelphia Baroque Orchestra Tempesta di Mare, whose upcoming project, ‘Hidden Virtuosas,’ celebrates the women musicians of 18th-Century Venice.