by Anne E. Johnson

Published September 12, 2022

‘No other paint medium feels quite so pure, nor reflects light so beautifully. Whether distemper stage settings are lit by candle, oil lamp, incandescent lights, or LEDs, the scenic art literally glows.’

Opera has always been a spectacle, enveloping the audience in sight and sound. On the American early-opera scene, the audible aspects—the voices, the instruments, even effects like a thunder clap—are commonly governed by some sort of historically informed approach. Choreography and costumes, too, are often developed based on historical research. But one essential element is often left out of the equation: set design. That is beginning to change, thanks to the groundbreaking work of Wendy Waszut-Barrett.

When Chicago’s Haymarket Opera opens its new production of Monteverdi’s L’incoronazione di Poppea on Sept. 24, some fruits of Waszut-Barrett’s labor will be on display, giving the opera a look approaching what Monteverdi himself might have seen, and using colors as intense as the composer’s seconda pratica dissonances.

The association between Waszut-Barrett and Haymarket began after the opera company’s general director, Chase Hopkins, read a 2021 New York Times article about her discovery and preservation of 19th-century sets moldering in an old theater in Colorado. Hopkins brought her on board to create the scenic design for Haymarket’s June 2022 production of Joseph Bologne’s L’Amant anonyme.

“She’s a goldmine of interesting information,” Hopkins says, “and she is bringing history to life on the stage at Haymarket.” Hopkins found her contribution unique not just in her designs, “but also through the techniques she paints with and the mixing of the paint itself.” And the choice of opera gave her plenty to work with.

The Coronation of Poppea, Monteverdi’s last opera, premiered during the Venice carnival season that started on Dec. 26, 1642, less than a year before the composer’s death. It represents a shift in his interest in terms of story, drawing from Roman political history rather than the Italian-flavored versions of Greek myths, like the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice, that Monteverdi had focused on early in his career.

As his source for Poppea, librettist Giovanni Francesco Busenello relied on the Annals of Tacitus, a book packed with lurid accounts of Roman political corruption and scandal. Poppea loosely tells the story of Nerone (a.k.a. the Roman Emperor Nero), married to Ottavia but in love with Poppea, who is in turn married to Ottone. Ottavia tries to force Ottone to murder Poppea, but the god of love stops him. Instead, Nerone divorces his wife and marries Poppea, who will now become Empress of Rome.

In an opera historically decried for its lack of moral center—the bad guys win—the soap opera-like emotional interplay among the characters makes Poppea a particularly rich lode of inspiration for the creative team. Visually, it boils down to one primal element: color. As it happens, color is at the core of Waszut-Barrett’s craft.

Her modern-day secret is a material that was well known to 17th-century theater artists: distemper paint.

“This paint system was the preferred method of scenic artists for centuries,” Waszut-Barrett tells EMA. “The colors are vibrant and the finish flat. It’s ideal for the stage with any type of lighting system.”

Distemper paint is a deceptively simple formula, consisting of only two ingredients: pigment (color) and binder (glue). She describes it as an extremely efficient process, leaving behind no waste at the end of a production.

Waszut-Barrett makes the paint herself using historical methods. The pigment comes from natural sources such as plants, minerals, and insects, although some colors are the result of chemical processes. “In historic scenic art studios,” she says, “blocks of pure color were ground into a fine powder prior to use. This powder was then transformed into a paste and placed directly on the artist’s palette.”

The pigment paste was then combined with animal-hide glue, a substance known as “size.”

Although any binder will work, size makes for the best colors under lights. Both the pigment and the hide glue were stored in a dried form, giving them an indefinite shelf life. It’s only when they touched moisture that they activate. Waszut-Barrett has developed a technique that works best for her: “I frequently soak the glue in water overnight and then slowly cook it to the consistency of a thick syrup the next day. One part concentrated glue in syrup form to one part water makes ‘strong size,’ a fabric priming product.” Further diluting creates a liquid called “size water.”

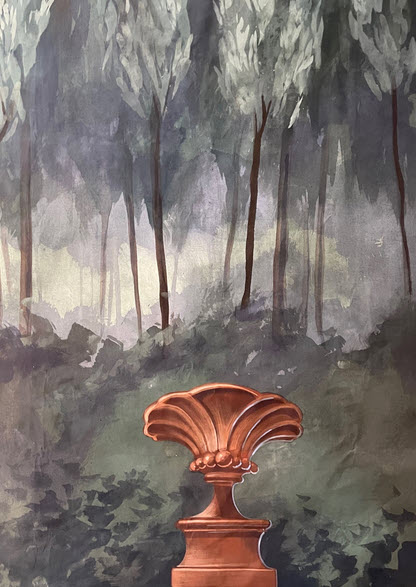

The physical sets for Poppea have been constructed in the “wing-and-drop” format, in which flat pieces (wings) on either side of the stage are painted to look three-dimensional. There’s a painted fabric upstage (the drop) and individual painted fabrics (shutters) that can help differentiate one location from another.

Waszut-Barrett finds many advantages to using distemper for these wood and fabric sets. “Unlike contemporary premixed paint, there are no added fillers or extenders that dilute the colors. Contemporary paints also have a limited shelf life and must be used within a relatively short period of time. This is not the case with distemper paint for the stage. In dry form, both pigment and hide glue have an extraordinarily long shelf life, one that can last for several decades or more.”

Its use on fabrics also trumps modern materials: “Unlike contemporary scenic paints, there is no successive paint layer build-up with each application. Distemper paint allows each opaque wash or translucent glaze to penetrate the previous layer. This reduces the overall thickness of the painted composition. As the colors are so vibrant, less paint is also needed to saturate the fabric, further contributing to a very thin and flexible paint layer on the fabric.”

She also likes the translucence that can be achieved as well as the unusual reflective qualities of the paint. The latter is the result of using a single large artist’s palette rather than separating colors in individual containers, thus causing a continuous process of blending and altering the hues. “Overall, the continued mixing and layering of paints will shift the painted composition under stage lights,” she says. “Colors that are not identifiable when the scene is bathed in front light, blossom when backlit. In my experience, no other paint medium feels quite so pure, nor reflects light so beautifully. Whether distemper stage settings are lit by candle, oil lamp, incandescent lights, or LEDs, the scenic art literally glows.”

Just because the colors are especially pure does not mean they are especially bright or dark. Research into artistic treatises and some extant scenery in the Czech Republic and Sweden limited her palette to yellow ochre, brown ochre, red ochre, vermillion, ultramarine blue, malachite, and Van Dyke brown—the darkest color she used. “Black paint was purposefully omitted from the color palette as it diminishes the overall reflective quality under stage lights,” she says.

Despite the luminous perks of this historic painting technique, there are drawbacks. First, there’s the difficulty of using it properly. “Poor preparation of the hide glue, contact with water, high humidity, and other factors can cause the binder to fail,” she says, “causing the paint to release from the fabric.”

And then there’s what happens to it over time. The Haymarket Opera will be challenged if it hopes to preserve Waszut-Barrett’s sets for the long term. “Unlike many contemporary paints,” she says, “distemper paint will reactivate when it comes in contact with any form of liquid. It is remarkable that any historic backdrop has survived the test of time, and each one is a credit to the artisans who properly mixed the paint and the stewards who maintained historical scenery collections over the years.”

As for the act of painting, Waszut-Barrett combines old and new techniques. “The backdrop and wings for Poppea were painted in the Continental Method, where the canvas is tacked to the floor. Paint brushes are attached to bamboo poles, which allow the artist to stand throughout the painting process. The borders for the production were painted on a motorized frame, allowing the architectural detail to be painted at arm’s length.”

Waszut-Barrett explains that the painter must take into account the distance of the audience from the sets, which would be at least 20 feet. “This necessitates a distinct separation of both color and value. This contrast is essential for scenic illusion on the stage, forcing the audience’s eyes to work. Photo realistic scenery, compositions with too much detail, lose their definition from a distance.” She likens the approach to that needed for painting the ceilings of cathedrals. “Upon close inspection, many of the painted compositions fall apart, revealing only dabs and dashes of color.” She applied this same “economy of brushstrokes” when creating the sets for Poppea.

Even as she teaches modern-day American companies about old materials and techniques, Waszut-Barrett sees a parallel with the early American period, when these European methods were rare. “The demand for painted scenery was often greater than the supply of artists for many Early American productions,” she says. Under her guidance, perhaps HIP sets will become more common for early opera in America, providing an additional element to transport audiences to another time and place.

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. Her arts journalism has appeared in the New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and Copper: The Journal of Music and Audio. For many years she taught music history and theory in the Extension Division of Mannes School of Music.