by Jacob Jahiel

Published December 10, 2023

Spotify dominates the music-streaming world, but one early-music listener says we have much better options

All I want for Christmas is for people to stop listening to classical music on Spotify.

For consumers of the genre, navigating the world’s largest streaming service is a headache — doubly so for listeners of early music. The platform has always been geared towards popular music, and there seems to be little incentive to change.

Sure, I have a Spotify account for my non-classical needs (or rather, I leech off of my parents’ family plan). For anything else, the process proves unwieldy, sometimes infuriatingly so. Spotify’s search function, whose ineptitude increases the older music gets, is near useless unless you search with utmost specificity. Having to choose only between “Albums” or “Songs” is an uncomfortable dichotomy, and the “Artists” field does not differentiate between composers and performers.

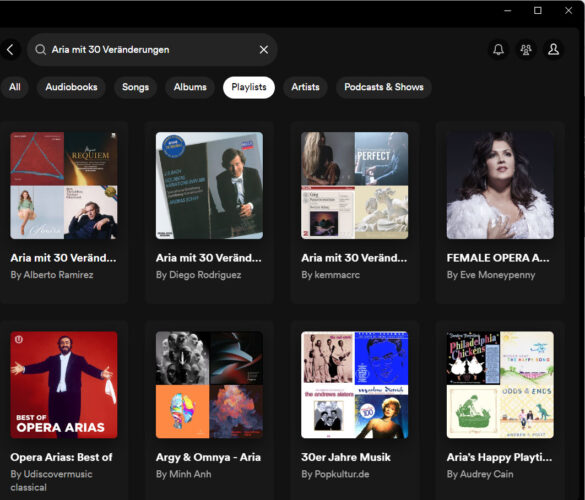

My list of grievances continues. Spotify’s text display is not well equipped for longer titles, clipping anything beyond the first few words and obscuring catalog numbers — the same goes for a list of performers. While Spotify is, for the most part, smart enough to realize that Aria mit 30 Veränderungen and the Goldberg Variations are the same piece, the two queries produce drastically different results. Spotify’s algorithm regularly makes period-inappropriate recommendations (sorry, plainchant and Pavarotti arias are not particularly similar), resulting in suggestions that range from farcical to inane.

These may seem like petty complaints, and most can be circumvented with some degree of skill and effort. But my point is that we shouldn’t have to. Fortunately, there are alternatives.

Four years ago, I enrolled in free trials for two classical music-oriented streaming platforms: IDAGIO and Primephonic. (The latter was acquired by Apple in 2021 and released last spring as Apple Music Classical.) For some reason I picked IDAGIO. My life has been infinitely better for it. Dear reader, I desperately wish the same for you.

The Sound is the Thing

First of all, both IDAGIO and Apple Music Classical (AMC) simply sound better. Whereas Spotify compresses audio files for reasons of storage and ease of streaming, these two competitors offer an option for lossless audio quality, meaning the sound is more or less identical to the original source. (Take that my smug, vinyl-collecting friends.)

For something like a Brahms symphony, it’s a difference in sound quality that only diehard audiophiles would likely notice. However, when it comes to period instruments, or picking out single lines in complex polyphony where vocal timbres are more similar than, say, a modern orchestra, I find the difference to be far more pronounced. Lossless quality can be the difference between a harpsichord sounding tinny or reverberant and a gut string nasal or silky.

IDAGIO’s audio quality options:

Just as important is their navigability. On Spotify, your options for discovering new things are limited. You might find a new group by cross-referencing artists who have recorded a particular piece or, conversely, find new tunes by sorting through the discography of a group you like. You might also choose to throw yourself on the mercy of the playlisted “radio” option, but as I mentioned earlier, doing so results in little more than a quasi-random ahistorical mush.

By contrast, IDAGIO and Apple Music Classical not only know the difference between Bach and Offenbach, but also allow you to sort through their catalog by period, instrument, composer, genre, performer, or by individual work.

IDAGIO even lets you filter these in combination:

Granted, neither platform is perfect: Sometimes the metadata is incomplete or inaccurate, so it still might take one or two searches to find what you want. Since it has more customizable filter options, IDAGIO can be more finicky and accident-prone, but by the same token you have more options to find what you want (or didn’t know you wanted).

Apple Music Classical search:

It’s nice to see, too, that early music is fairly well-represented across both platforms. IDAGIO’s “Browse The Catalogue” button takes you to a list of composers that includes not only the predictable Bach, Vivaldi, and Mozart, but also Monteverdi, Tallis, Gesualdo, Corelli, Cavalli, Strozzi, Lully, Marais, Purcell, and Rameau.

Similarly, their “Featured New Albums,” “Trending Albums,” “IDAGIO recommends,” and “Critically Acclaimed Albums” carousels consistently have a strong showing from the historically informed scene:

In terms of featured content, Apple Music Classical skews a little more towards the modern scene. The “Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Essentials” playlist, for example, is more Muti than Harnoncourt, but I spot Ensemble Pygmalion, Bach Collegium Japan, and MusicAeterna in the mix. Keep in mind that, whereas IDAGIO is a Berlin-based company, Apple Music Classical is firmly rooted in Silicon Valley, which may be a source of the somewhat disparate cultural currency early music holds in each respective app.

In certain areas, Apple Music Classical strikes me as a bit unfinished compared to its counterpart, which is odd since Apple had more than two years since acquiring Primephonic to complete what ostensibly could have been a simple rebranding. For instance, while a fair handful are historical, only 28 instruments or voice types are included in its “Browse Instruments” tab, compared to IDAGIO’s 483. Then there is the fact that Apple Music Classical does not yet have a browser version, leaving iPhone or iPad your only option (an Android app is still in development).

In the App Store, Apple Music Classical earns consistent praise for an “About” feature that allows you to explore brief historical descriptions pertaining to what you are listening to. While I applaud the attempt and hope to see it polished, the quality and accuracy of these descriptions vary. The description for “About the Viola da Gamba,” for instance, contains more than a few misleading generalizations and factual inaccuracies. Amusingly enough, while that entry resembles something pulled straight from an undergrad music history essay, the entry for J.B. Lully is hilariously dense for general audiences.

While IDAGIO has no such feature, it does allow you to access an album’s liner notes, which is perhaps my favorite aspect of the platform. If, like me, you are constantly running to find a translation, a generally good habit particularly vital to early music, this is an invaluable tool. Plus, liner notes usually provide well-researched and relevant historical detail, often saving me a trip to Grove or Wikipedia.

IDAGIO’s largest weakness, on the other hand, is its library size; here both Spotify and Apple Music Classical have it squarely beat. (Apple Classical boasts the largest classical library of any streaming platform at over 5 million tracks, compared to IDAGIO’s 2 million.) I can find what I am looking for in IDAGIO about 95% of the time—the remaining 5% I must turn to Spotify. Nonetheless, it’s a drawback outweighed, at least for me, by IDAGIO’s superior searchability.

Costs & Payments

A few words on artists’ compensation. Traditional royalty models, which pay artists per track played, are punishing for classical albums whose tracks tend to be longer and less numerous. IDAGIO utilizes a far more ethical model that pays per minute, which means that harpsichordist Jean Rondeau isn’t being penalized for taking all of the repeats in the Goldbergs. While Apple Music Classical has historically shelled out markedly higher royalties than Spotify, it appears to still use the standard, per-track licensing agreement of its parent app. No current streaming revenue model is great from the financial standpoint of the artist, so it’s still a question of choosing lesser evils. But the difference between mere exploitation and outright robbery is, in the end, a meaningful one, and something the consumer should consider.

Then, of course, there is the cost to the consumer. Apple Music Classical is included with an Apple Music subscription, currently $11.99 per month. That places it two dollars higher than IDAGIO’s monthly $9.99 Premium Plan (there is also a limited free version with ads), but considering you also have access to your non-classical libraries in the parent app, this may be the more economical option for most people. An individual Spotify Premium account currently costs $10.99.

Also worth noting: For a $10.99 per month Streaming Plus Plan, the up-and-coming Presto Classical app promises many of the same features as Apple Music Classical and IDAGIO. It boasts over 200,000 classical and jazz albums (34,000 of which support high-resolution audio), offers an option to access liner notes, and features a per-minute payment model. Though not yet as impressive as either IDAGIO or Apple Music Classical in terms of browsing, Presto is one to watch, particularly if you are also into jazz.

My loyalty still remains with IDAGIO, if anything because I like my liner notes with translations, and because I feel that Apple already has an outsized presence in my own technological existence. Both, however, are leaps and bounds better than Spotify.

Jacob Jahiel is a writer, arts administrator, and viola da gambist living in Baltimore. He also works for the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and scrapes away at various historical bowed string instruments in his free time.