by Jeffrey Solow

Published December 19, 2025

Bach: The Cello Suites by Edward Klorman. New Cambridge Music Handbooks; Cambridge University Press, 2025. 169 pages.

With no known autograph manuscript, there’s a fog of uncertainty surrounding the suites

Little was known about J.S. Bach’s Six Suites for solo cello when they were first published in 1824, about 100 years after they were composed. The last several decades — indeed, the past several years — have seen a crescendo of knowledge concerning the genesis, sources, and history of the suites. This is certainly to be welcomed, but it also makes it difficult to keep current with the latest information about them, since anything committed to print, even just a few years ago, is likely to become outdated as new information is unearthed or new theories put forward.

The major contributing factor to the fog of uncertainty surrounding the suites is that no autograph manuscript has ever come to light, assuming one ever existed. What has survived are four handwritten copies of the set (one by Anna Magdelena Bach, one by Johann Peter Kellner, one by the copyist Johann Nikolaus Schober, and one by an anonymous copyist). The discovery and study of these manuscripts over time has both informed and misinformed cellists and scholars ever since that first edition was published in Paris. (Showing how precarious historically transmitted sources can be, the entire run of the first edition survives in just a single exemplar!)

When I was a student, it was “common knowledge” that Anna Magdalena’s manuscript was copied directly from her husband’s lost fair copy, and Kellner’s was based on Bach’s lost working manuscript. The two other copies, both derived from an additional (lost) manuscript, either (depending on the musicologist one relied on) were corrupted by the copyist of that lost manuscript or reflected a revised version made by Bach himself and thus were the most reliable among the sources.

Edward Klorman’s book is not only the newest, and therefore the most up-to-date entry in the long catalog of Bach Suite studies, it is also outstandingly comprehensive in scope.

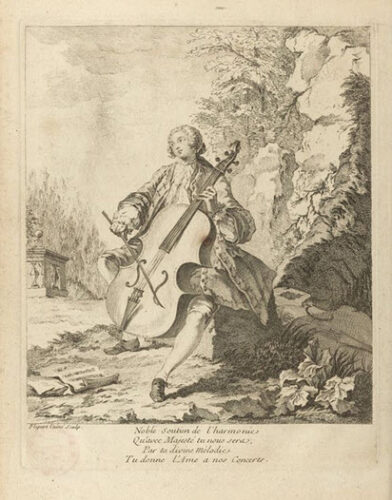

The first of the five chapters discusses where the suites were likely to have been composed and what influenced their formation. Klorman also covers what constituted “the cello” in Bach’s time (including the violoncello da spalla — an instrument supported by a strap and played horizontally) as well as how the cello bow was most likely held in Bach’s circle (underhand, gamba style).

In chapter two, a description of the characteristics of the various dance movements that make up the suites is followed by an examination of preludes, which display different attributes. Klorman concludes with a deep dive into the fourth suite, including a speculative religious view of its Prelude, inspired by an essay by Carl Schachter, interpreting its structure through the lens of Christian symbolism.

Chapter three discusses the likely genesis and transmission history of the manuscript copies. This presentation is particularly valuable for cellists looking to determine where to put their trust. (The inclusion of a schematic “stemma” showing the interrelationships among the various sources and early editions would have helped the clarity of Klorman’s discussion.)

The two concluding chapters cover the transmission of the sources, the earliest editions and other influential 19th- and early 20th-century editions, known performances, and reception history (including concert reviews) from 1720–c.1900 and after 1900. Klorman also discusses editions with piano accompaniments. He explores the monumental impact of Pablo Casals, the first cellist to record all six suites and the person most responsible for fixing them into the musical public’s consciousness. The final topic concerns spin-offs and influences of the suites both in music and beyond.

There are also 13 illustrations, numerous musical examples and a bibliography that serves as a great resource for further reading and study.

Klorman notes that the suites were originally part two of a set (part one being the violin soli) and offers Christoff Wolff’s theory that, due to the upset caused by Bach’s first wife’s death, he never made a fair copy. I think it likely that he did make one but presented it to Christian Linike, Cöthen’s court cellist, for whom Bach probably composed the suites. Thus, only Bach’s working copy remained in his files where it served as the ultimate source for all surviving copies.

Additionally, Klorman offers Andrew Talle’s painstakingly researched theory that Kellner’s copy was made from a lost copy of the suites made by J.S. Bach’s nephew Johann Bernhard Bach der Jüngere (“the younger”) that was carried by him when he relocated to Ohrdruf, near Franckenhain where Kellner lived. While Klorman ends his discussion at this point, if Talle’s reasoning is followed to its conclusion, it means that Kellner based his copy (containing all the suites) on a source carried from Cöthen in 1720 or ’21, thus proving that all six suites had to have been completed before J. S. Bach moved to Leipzig in 1723. This scenario would lay to rest one of the suites’ greatest mysteries!

For his discussion of the sources and earliest published editions of the suites, Klorman relies extensively on Talle’s edition (Bärenreiter, 2018) and the revised preface of its third printing. This has a special resonance for me since Talle revised and replaced his original preface largely because of conversations with me, particularly regarding the idea, advanced by James Grier in his 1996 book The Critical Editing of Music, that an intermediate copy of the suites separated J.S. Bach’s autograph manuscript and Anna Magdelena’s copy. (In other words, she did not directly copy Bach’s autograph.)

Although the musical examples presume an ability to read music, Klorman recognized the challenge of writing for diverse readers including amateur and professional cellists (and violists, who also play the suites), non-specific musicians, and general-interest readers. The single exception to general accessibility is in chapter 2, where his analysis of the fourth suite requires a knowledge of music theory to fully appreciate.

I cannot praise this book highly enough and consider it a must-have for cellists and violists, as well as for any music lover who wants to learn more about the suites themselves.

Jeffrey Solow, professor of cello at Temple University in Philadelphia, performs as a soloist and chamber musician, transcribes and edits music for the cello. His articles and reviews have been published by The Strad, Strings, American String Teacher, The British Cello Society, and The Violoncello Society of NY.