by Anne E. Johnson

Published July 1, 2025

At the Blue Hill Bach Festival, in coastal, idyllic Maine, ‘every concert is in a different location. A farm one day, or on somebody’s porch. Or in a couple of very different churches. You might be playing the St. Matthew Passion, or you might be doing a silly scene from Purcell.’

“It’s not on the way to anywhere,” Rosie van Reesema says of historic Blue Hill, Maine, “which makes it a magical place. There’s a vibrant arts scene, so when you’re going, you’re going for that.” Especially in the summer, when the regular population of under 3,000 explodes to 10,000.

Van Reesema is the new executive director of Blue Hill Bach, a period-instrument festival in the idyllic Maine town. This summer, the festival celebrates its 15th season, July 15-19. With Bar Harbor and Acadia National Park just across the bay, Blue Hill Bach is a stop on the arts-and-outdoors tourism circuit.

The festival grew out of single summer concerts back in 2011 and 2012, a collaboration by mezzo-soprano Marcia Gronewold Sly and organist and conductor Jonathan Dimmock. Sly, who recently stepped down as the festival’s executive director, says Dimmock was interested in the pipe organs in Maine. “There is a wonderful organ at St. Francis Episcopal Church in Blue Hill, and one day he suggested to me that we make a recording there of the aria ‘Gott soll allein’ from Cantata169.”

The result was a period-instrument performance of the whole cantata. “The audience was at capacity in the church. There was instant buzz. I guess the community was ready for it,” says Sly.

Among the musicians she enticed to participate was oboist Stephen Hammer. “Somebody had said if you can get Steve, you will have struck gold.”

In 2013, the single concert was expanded into a three-concert festival. Dimmock bowed out, and Hammer became artistic director. “At some point I said to Marcia, since it’s a five-hour drive from Boston and further from anywhere else, it seems a shame to go all that way and just play one concert. Why don’t you have a festival? And she said, ‘Oh, what a good idea!’”

After 15 years as executive director, Sly has just been replaced by van Reesema, the festival’s operations manager for about a year. “I’m excited to dive into Marcia’s world,” van Reesema says. For her new, full-time position, she relocated from Brooklyn. She grew up about 20 minutes from Blue Hill, in Orland, and confesses that “my husband and I were plotting ways to get back to Maine.”

The festival typically does one program at St. Francis By The Sea and one in the First Congregational Church of Blue Hill, plus an event in a floating venue. Each of the three programs has a theme, Hammer explains. “It’s not especially an early-music audience, but they like fun and interesting things, so I try to find an unusual theme for each program and do some repertoire that you don’t get to see and hear.”

The themes have ranged from educational (Bach in Weimar in 2016) to playful (2015’s Surf and Turf featured Handel’s Water Music and Bach’s Hunt Cantata). This year is a retrospective of works that have been played in past seasons. The first program, Awakenings, uses pieces from the two concerts before the event grew into a festival, ending with Wachet auf, Bach’s Cantata 140.

Devising programs has been a continuing challenge, Hammer admits. Many of his choices were inspired by people he’s worked with, including James Richman, Joshua Rifkin, and Thomas Forrest Kelly. “They all had wonderfully ingenious programming ideas, and I’ve shamelessly stolen from all of them.”

It took some convincing to put together Dido and Aeneas in 2018, but they brought in Baroque dance specialist, Carlos Fittante, to choreograph and the evening was a wild success.

Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons in 2019 also met with some resistance from Hammer, which Sly understood. “The Four Seasons is just such a trope, but people love it. We did it with narration of the sonnets” by local resident Noel Paul Stookey — the Paul of Peter Paul and Mary. He’ll repeat that recitation as part of the retrospective.

Their Four Seasons featured projected images by local photographer Dick Leighton. That visual element helped them use the piece for their virtual festival during 2020’s COVID restrictions. The virtual festival also included Grant Herreid’s Pocket Beggar’s Opera. “Three of us played the instruments,” says Hammer. “We had each character record their role from their house.” A student of conductor John Finney edited the parts together.

Currently the festival’s period-orchestra conductor is James Kennerley. The musicians, who come from Maine and out of state, tend to return annually. “I think of it as a repertory company,” says Hammer, who still plays oboe with them although he’s moved to Los Angeles. “At a lot of festivals, the musicians just come and do their thing and leave. We want people to feel part of it.”

“They are all early-music specialists,” says Sly. Their impressive roster includes Lisa Rautenberg as concertmaster and Anne Trout on violone. Sly credits Hammer’s connections: “He can pick up the phone and say, ‘Hey, don’t you want to come to Maine and make beautiful music together? It’ll be like a vacation. We won’t pay you enough, but we’ll feed you lobster.’” (They do, in fact, throw the musicians a lobster dinner.)

Van Reesema sees an advantage to mixing in players from out of state, which allows “our Maine musician to have their network extended. Usually it’s such a small pool of people who all do the same thing in Maine.” She believes this exposure helps young musicians “not feel so boxed in.”

One of the out-of-state regulars is Handel and Haydn Society cellist Sarah Freiberg, who lives near Boston. She’s been coming since the second year and loves the vibe among musicians: “Everybody works really hard. You all get to eat together and hang out together. For five or six days you’re just concentrating on producing these really lovely concerts. You’re playing this wonderful music for wonderful people in a wonderful place. Why wouldn’t I go?”

She also enjoys the variety: “Every concert is in a different location. You might be playing at a farm one day, or it might be on somebody’s porch. Or in a couple of very different churches. You might be playing the Saint Matthew Passion, or you might be doing a silly scene from Purcell.”

The audience seems to enjoy it, too, year after year.Hammer says many East Coasters time their visits “during festival week so they can come to all the shows.” Freiberg knows several Boston-based people who go annually. “They’re so excited to have music up there in the summer. They love being there, and they help out.”

The natural surroundings lure musicians and audience members alike. “There are all these little inlets and tiny islands,” says Freiberg. “It’s just gorgeous. The Blue Hill itself is not much of a mountain, but you get really nice views, and it’s much cooler. I go for long walks, and take tons of pictures, and I make calendars and give them to everybody.” She also loves the town of Blue Hill and its “tiny old houses, old churches, beautiful gardens. It just takes me back to an earlier, quieter time.”

Still, Sly believes about half of their always-sold-out audiences are local. That’s why the festival tries to reach a wider swath of the region. Besides programs at the Episcopalian and Congregational churches in Blue Hill, the festival does an event called the Baroque Café, always at a non-traditional venue.

One of those is David’s Folly Farm in nearby rural Brooksville. “It’s an unfinished barn on a working farm with donkeys,” says van Reesema. “They just had a baby donkey last year named Ginger.” Billed as a family event, they bring in food trucks, and people come an hour early by busses, since there’s not enough parking on site. People have a picnic. Then everyone goes into the barn for the concert.

The Baroque Café, always a secular program, has also performed at the Atlantic Boat Company. “The guys at the boatyard get really into it and put sails up on the walls and build us a stage,” says Sly. “We put out tables with checked tablecloths and make it a real picnic kind of environment.” Other venues have included a glass house at a local landscape company and a beautiful large cottage on Blue Hill Bay. “We try to keep finding new places.”

Although at first the festival was just the three concerts, there are now ancillary events, such as daytime lectures on that evening’s program. All the additional events are free. Although there is a charge for the concerts, kids under 18 attend free, and college students get a big discount.

Growing the Talent, Growing the Org

There have been string masterclasses in past years, but 2025 will introduce the first vocal masterclass, taught by tenor Gene Stenger, aimed at young singers from area universities in Blue Hill Bach’s new internship program. “Right now it’s a choral internship,” says van Reesema. “That might be changing in the future.” In addition to the masterclass, “they will participate in the behind-the-scenes element and work with the stage manager.” They will also join the chorus in the festival finale.

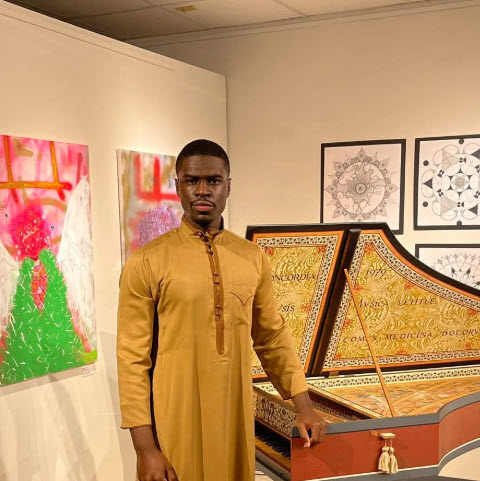

Another way Blue Hill Bach shows interest in early music’s future is through its Marville Young Artist Fellow program, established in 2013. The recipients tend to remain loyal. “They may come back a year or two later and become members,” says van Reesema. Among the former fellows participating in the 2025 festival are organist and harpsichordist Abraham Ross and tenor Zachary Fisher, who is now on the festival board. This year’s fellow is Shelby Yamin, a violinist with a fast-growing reputation and a graduate of Juilliard’s historical-performance program.

The festival’s commitment to young musicians will likely grow in the coming years. “Since public school music education is getting more and more tenuous,” Hammer says, “hopefully we can find something that brings in the kids on the peninsula.” But it needs to go beyond summer, to develop “more of an educational program during the other 51 weeks of the year.”

Currently there are two regular Blue Hills Bach performances outside of the festival. One is a holiday program, usually a scaled-down Messiah, with string quartet, bass, and continuo organ and harpsichord, and a small chorus. That concert is all Maine-based performers, including choristers from University of Maine, Orono (where Sly used to teach), plus younger singers from nearby private high schools. The other extra-festival event is a springtime concert for Bach’s birthday, which also uses primarily local singers, although the instrumentalists come from all over.

The leadership change is happening as the organization continues to grow. There are 400 names on their current donor list. “That first year we had seven donors,” Sly recalls. The annual budget has blossomed to $115,000 from the original $5,000. Hammer remembers those early days: “The board was very much a working board. We would all move the furniture together.” He adds, with a chuckle, “I haven’t moved furniture in a few years.”

But that success does not mean unchecked growth. “People really like stability,” says van Reesema. “We have butts in seats every single year, and so something is going right. What I’m not looking to do is come in and provide too much new too fast.”

There are practical considerations too. “We depend on members of the community to provide housing for our artists, so there’s a limit to what we can expect.” Sly agrees that the festival is currently in a good place. “I think that our audience likes what we do, and we have real credibility in terms of the standard of our performances. They stand up next to any early-music ensemble.”

Even if nothing changes, says Sarah Freiberg, the audience will keep coming. “People are passionate about the possibility of early music on early instruments in Downeast Maine.”

Anne E. Johnson is EMA Books Editor and frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently reviewed the book Inclusive Music Histories: Leading Change through Research and Pedagogy by Ayana O. Smith.