by Anne E. Johnson

Published March 11, 2024

Traditional kora music from West Africa pre-dates the European Baroque. For New York’s Music Before 1800, a goal is to embrace the whole world, not as ‘world music’ but as niches of historical music that deserve an equal spotlight.

Does the term “early-music concert” conjure the image of a modern classical guitar and the African gourd harp called a kora? No? Bill Barclay, in his first season as artistic director of the New York production company Music Before 1800, hopes to change that.

Barclay has programmed a March 24 duo recital called “Mali Before 1800” at Corpus Christi Church in Manhattan, featuring Malian kora master Ballaké Sissoko and South African guitarist Derek Gripper. “I see it as one of the most important things that I could do with Music Before 1800,” says Barclay, “to expand early-music vocabulary beyond Western European genres.” His goal is to “embrace the whole world, not as ‘world music’ but as specific niches of historical music that deserve a completely equal spotlight.”

The idea of bringing kora music to Music Before 1800 (MB1800) germinated when Barclay was music director of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London. He and guitarist John Williams were developing a concert series. Through Williams, he met Gripper, whom he introduced to kora player Tunde Jegede. At first, the three planned to play the famous traditional kora piece “Jarabi” together. But Williams realized that Gripper and Jegede needed their own night. “The concert they performed was so ecstatic and wonderful, and people went mad for it,” Barclay says.

Speaking via Zoom from his home in Cape Town, Gripper recalls his first musical meeting with Jegede at the Globe. “I think we arrived on the ‘day of,’ and we had a lot of pieces in common, so it was a little bit like a jazz gig. I realized this was the first time I was seeing a kora player live.” Gripper did, however, already have a long association with kora music.

He had long felt disillusioned with the classical guitar repertoire. “In around 2001 I was given a burned CD that said ‘Toumane Diabaté Kaira’ in Sharpie.” As it turns out, the Diabaté family is central to the kora’s father-to-son oral tradition in Mali. “I was really blown away,” says Gripper. “It was like listening to Bach but with a groove, and the virtuosity of Keith Jarrett. Toumane was playing the most amazing improvisations over traditional tunes while keeping the accompaniment going, this incredible sunshine coming out of the music.”

The experience made Gripper rethink his own instrument. “That was a benchmark for me of what a string instrument should be able to do. I had to just make do with what a six-string guitar could do, which wasn’t much.” But then he discovered the Renaissance vihuela, which has six sets of strings. “Through a year of playing that music, when I returned to listening to Toumane’s music, suddenly the way to approach it made sense.” He began to transcribe what he heard.

‘It was like listening to Bach but with a groove…this incredible sunshine coming out of the music’

That’s no small feat, given the complexity of kora music. Among the many kora players whose work Gripper wrote down was Ballaké Sissoko, his musical partner for the upcoming MB1800 program. Via a translator, Sissoko sent me a description of his instrument’s place in the community: “Kora is a traditional instrument that comes from the griot or djeli families.”

The families who act as griots are the ones “who tell stories of the past,” Sissoko says. “In our oral traditions, griots were telling the stories or tales to people—stories of wars, of marriages, of families. They were the witnesses of life.” (The Mande word “djeli” is the same concept as “griot,” a word that may have French colonialist roots, according to musicologist Kamilla Arku, who wrote the program notes for the MB1800 concert.)

There is a tradition of singing with the kora. However, that’s not what Sissoko usually does: “I play instrumental music with no words, so my music can sometimes make a reference to a special event of this past life, but it is difficult to explain.”

The 2023 documentary Ballaké Sissoko, Kora Tales, explains it well. Co-directed by Lucy Durán, of the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), and Laurent Benhamou, the film traces the history of the kora in Mali, to which Sissoko’s immediate family is intrinsic. Although the kora is an ancient instrument in the Gambia and Senegal, its arrival in Mali is recent.

Modibo Keita, the first president of Mali when it gained independence in 1960, thought of the kora as symbolizing a free Africa. He invited two kora players from the Gambia to join the new National Instrumental Ensemble of Mali (NIEM). One was Djelimady Sissoko, Ballaké’s father. Ballaké was seven at the time. When his father died in 1982, the 13-year-old was already proficient enough take over his father’s chair in NIEM.

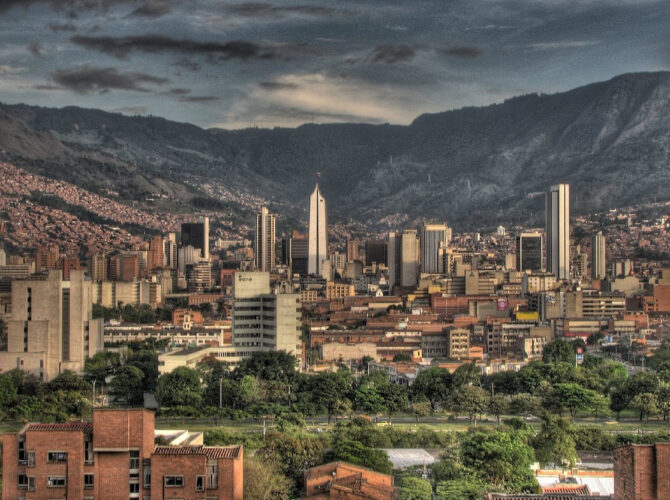

Sissoko still lives in the house his father built in Bamako, Mali. Over the decades, Bamako has become a world hub for kora players. “Just by listening to traditional music of Mali, you can truly discover the whole history of the country,” says Ballaké’s cousin, another Djelimady Sissoko, who teaches traditional music at L’institut National des Arts in Bamako. “In each piece of Malian music there is a hidden story. You have to search to find it.”

Ballaké’s mother, Luntandi “Touti” Sakiliba, is also a griot (although most are men). “In our family, no one learns to play the kora,” she says in the documentary. “It’s innate.” It’s no surprise that, as Sissoko’s aunt says of her gifted nephew, “If you touch him, it produces a melody.” Singer Arthur Teboul, who has performed with Sissoko, compares his fingers to “a runaway river, laughing like a stream. You feel it like a current that carries the soul.”

Early Music, Modern Instruments

“To me it sounds like magic,” says Bill Barclay.

But does it belong on an early-music series? Barclay has no doubt about it. After all, it is early music. “It predates Baroque music, that’s for sure,” he says. “That’s what’s fascinating about Africa. It’s always been there, and it’s the roots of all of our music, and we so rarely take the time to go back and check in with what has still survived. It’s an amazingly unbroken tradition.”

Their relationship to the early-music scene was on Gripper and Sissoko’s minds when they agreed to join the MB1800 season. They pondered whether traditional instruments were a necessity. “But immediately that knocked me out of the equation because I’m not playing an early instrument,” says Gripper. “I’m playing a modern classical guitar with nylon strings.”

Perhaps surprisingly to the non-expert, Sissoko is also playing a modern instrument, Gripper explains: “Ballaké was very emphatic that he’s never playing the traditional kora again! It has leather tuning rings, and those are really difficult to tune. You go to Bamako now, and everybody’s got koras with guitar tuners on all the strings. It’s practical. But the string is breaking over metal, so the sound is very different.” Originally the strings were leather. Then players started using fishing nylon, which brought the tuning higher. Koras are now typically strung with harp strings, which Gripper says causes a clearer sound.

That’s all fine with Barclay. “I would hate to just try to present, say, music from Sri Lanka 400 years ago, or Carnatic music exactly as it was before the West found it. Because our ears are different. We don’t even treat Bach that way, do we?” As he understands the kora tradition, it fits into the early-music scene because “its heart is in improvisation, in reinterpretation, and in personalization. Not in historical accuracy or authenticity, whatever those words mean to us now.”

Improvisation and interpretation are the name of the game for kora performance. “The music we play together,” says Sissoko, “is based on our compositions and developed by our imagination. We like to use musical structures and make them move depending on our emotion.”

They improvise on a finite number of pieces. “It’s a little bit like the Baroque suite,” says Gripper, “where you had like six dances, maybe eight. You had a gigue, you had a minuet, but of course every time someone wrote it, it was different.” He describes the kora piece “Jarabi” as “a little more like what an allemande is in the Baroque world than an actual composition.”

Gripper sees kora “improvisation” as existing on a spectrum between written music and extemporaneous composition. “My master class in that was sitting in a courtyard in Bamako at 2:00 in the morning drinking green tea — they have this very strong green tea that has psychedelic properties — and a kora player called Djelifily Sako was playing ‘Jarabi.’ He played it for about half an hour, and every moment that he played was something new for me, but every moment that he played was something familiar. And that was quite mind-boggling.”

Toumane Diabaté, Gripper’s original kora inspiration, first put it into words for him. “He made it clear to me that he called it ‘spontaneity.’ I said, ‘Oh, you mean ‘improvisation,’ and he said, ‘No.’ It’s more like a radical form of interpretation.”

The more Gripper learns about this “radical interpretation,” the more applicable it seems to the classical tradition. “We have this ability to improvise with nuance, articulation, and accent, even if the notes are the same. Anybody who’s played a piece of Bach for 20 years knows that. There’s a million different ways, and every day it’s different, and you’re always searching.”

All of this is relevant to early-music listeners and players alike, Gripper believes. “There’s this shared human way of making music which is still in a place like Mali. I think if you’re learning the viola da gamba now and you want to break out of the score and improvise, spending some time listening to a kora player is one of the best things you can do.”

He warns that the current approach of Academia is too limiting for early musicians. “We do have these wonderful performance-practice techniques from back in the day, but we also have intact traditions all over the world of people who didn’t go through the kind of Academy training that classical musicians did, and I think that’s a resource that is super important to get into.”

‘If you’re learning the viola da gamba and you want to break out of the score and improvise, spending some time listening to a kora player is one of the best things you can do.’

Gripper recommends, for example, that early-music programs show their students Lucy Durán’s documentary series Growing into Music. “They tracked virtuoso musicians in five cultures that used oral traditions, and they documented how their children are learning. These source materials are as important as the six texts that we have on how they may have trilled Rameau’s music.”

In comparing the kora tradition with classical music, deeper issues than the music itself can arise. Gripper is torn between his reverence for Bach and a dissatisfaction with the classical music milieu. “During the apartheid years in South Africa,” he says, “classical music represented a kind of European culture which people aspired to, the ruling class. I think that the character of classical music has been influenced by that idea, the pomp of it. With that grandiosity comes a lot of loss of nuance, of rhythm, of swing, or even sex.”

That same defiance of elitism is at the center of Barclay’s decision to present Malian music. MB1800’s concert theme this year is “The French Touch,” he says. “If you’re going to do a deep examination of French history, you have to talk about its colonial history. That includes Mali. And the griots of Mali and the degree to which they have incorporated the French language and the French culture and turned it into their own mix.”

Barclay distinguishes this program from an MB1800 concert earlier this season, featuring music of the Chevalier Saint George. “He’s from Guadalupe, and the Chevalier’s music, in the French galant style, was composed alongside his efforts to create abolishment of slavery in the French colonial islands. But he didn’t compose his music in Guadalupe.” Musicologist Arku points out that contemporary performances of this music necessarily “contain a multitude of contradictions; they conjoin a mythic past with a more complicated present.”

As intriguing as the kora tradition is to Barclay, in practical terms it was not an easy choice for the MB1800 series. “I knew that my core subscribers were not likely to leap out of their seats for Malian historical music,” he admits. So he found a co-producer, the New York-based World Music Institute. MB1800 and WMI plan to make this the start of an annual collaboration. For next season, Barclay has his eye on a group from Palestine. “We are trying to bring other voices into the early-music conversation.”

Anne E. Johnson is a freelance writer based in New York. Her arts journalism has appeared in the New York Times, Classical Voice North America, Chicago On the Aisle, and PS Audio’s Copper Magazine. She teaches music theory and ear training at the Irish Arts Center in Manhattan. For EMA, she recently reviewed Seven Times Salt’s album ‘Easy as Lying: Music of Shakespeare’s Globe.’