by Paul Murphy

Published July 12, 2025

Music and Modernity in Enlightenment Spain by Ana P. Sánchez-Rojo, Boydell and Brewer, Woodbridge, 2024. 298 pages.

In Ana P. Sánchez-Rojo’s Music and Modernity in Enlightenment Spain, we have a fascinating and long-overdue deep dive into an often-overlooked, essential component of European music, culture, science, and philosophy. Her work enlightens our understanding of the Enlightenment in Spain and is presented in a truly captivating read.

The author’s thorough introduction provides crucial context and background for the four chapters that follow: “Critics versus Musicians”; “Music, Medicine, and Tarantism in Madrid, 1787”; “Cosmopolitan Opera”; and “Bourbon Sentimentalities on the Musical Stage.”

She begins with a question posed in 1782 by the French geographer and poet Nicolas Masson de Morvilliers: “What does Europe owe to Spain?” This provocative and offensive question summed up the European misperception of Spain as “dead weight” for modern Europe, rooted in the decadencia following Spain’s Golden Age of the 16th and 17th centuries. It is also the perfect scaffold not only for building the case for the modernization that was occurring in 18th-century Spain, but also for investigating the very notion of modernity itself.

Sánchez-Rojo introduces us to authors who took great issue with Masson de Morvilliers’s view and consequently strove to modernize Spain, as well as to the “apologistas of Spain,” those consumed with maintaining the status quo and eager to rebut any negative opinions of current Spanish culture, whether foreign or domestic. She highlights composers and genres that, regrettably, are still unfamiliar or unknown to many, such as the Catalan composer Pablo Esteve and his El teatro y los actores agraviados (The Slighted Theater and Actors). The work is a tonadilla or short musical comedy performed during the intermissions of stage plays, a genre that Sánchez-Rojo explains “possessed many tools fit for the satire and criticism widespread at the time of the apologista polemics.”

Chapter 1 deals with the boom of the Spanish periodical press in the 1780s and the acrimonious debates played out between professional musicians and critics. Professional musicians in this context were largely those employed as chapel masters, organists, composers or authors, and those immersed in the world of Catholic liturgical and musical tradition. They composed multi-part counterpoint, directed choirs, taught young choristers, and often wrote music treatises preserving their inherited musical traditions. On the other hand, the late 18th-century press boom gave rise to a new source of modernization, the critic. As Sánchez-Rojo writes, these were authors who “disregarded traditional social structures and modes of communication.” They “embraced modernization [and] demanded swift changes to centuries-old ways of doing things.”

She presents the conflict between these two opposing cultural forces through two case studies, starting with an essay entitled “Discourse 97” and the response played out in the journal El Censor, which, between 1781–1787, ran nearly 200 weekly essays “satirizing Spanish citizens, their mores, religious practices, the clergy and the government.” She follows this with a return to Pablo Esteve’s tonadilla El teatro y los actors agraviados and the reception it received.

In Chapter 2, Sánchez-Rojo begins her captivating treatment of music and medicine with the case study of Ambrosio Silvan, a boy who appeared at the Madrid General Hospital in the summer of 1787 displaying a number of serious symptoms (facial paralysis, body spasms, etc.). His doctor eventually diagnosed his illness as tarantism; yes, that tarantism, the condition brought on by the bite of a tarantula which is said to cause hysteric behaviors and can only be cured by fast-paced dancing; cue the tarantella. Her imagery is compelling: “Despite their primarily rural existence, tarantulas crawled into urban Madrid’s imagination as residents feared their impending spread, whether real or imagined.”

The chapter includes extended discussions of musical medicine as well as tarantism in theory, practice, and satire. Sánchez-Rojo draws extensively from Francisco Xavier Cid’s scientific treatise, Tarantismo ovservado en Expaña of 1787 and includes several manuscript images of tarantella melodies for violin and guitar from Cid’s treatise to explain the dance’s most characteristic musical features. However, she errs when she states that the examples feature compound triple meter (they are in compound duple or quadruple meter). Similarly, she is right to highlight the expressive character of the augmented second interval found in the A harmonic minor scale but misplaces its location in the scale.

In Chapter 3, Sánchez-Rojo chronicles the 1787 premiere in Madrid of Medonte, in the newly re-opened Teatro de los Caños, the first Italian opera to take place in public theaters in 50 years. This shows how opera’s return to Madrid was often in uneasy conflict with a public more accustomed to comedy and opera buffa. She addresses the contemporary cosmopolitan ambitions for Madrid’s civic improvement through public projects, probes the idea of Italian opera as a means of “civilizing” Madrid’s public, and argues that official justification for Italian opera often reflected the Bourbon administration’s views on social order and policy.

To reveal how Bourbon sentimentalities made their way onto the musical stage, Sánchez-Rojo’s final chapter looks at the musical drama La Cecilia and its sequel, Cecilia viuda (Cecilia, Widow). In both works, the playwright and composer present “hard-working peasants, full of vim and vigor and obedient to their master.” She deftly shows how this idealized world, played out in music and drama, reflected the social and economic order cultivated by the Bourbon monarchies of both Charles III and Charles IV, and how it aligned with economic theories originating in pre-revolutionary France.

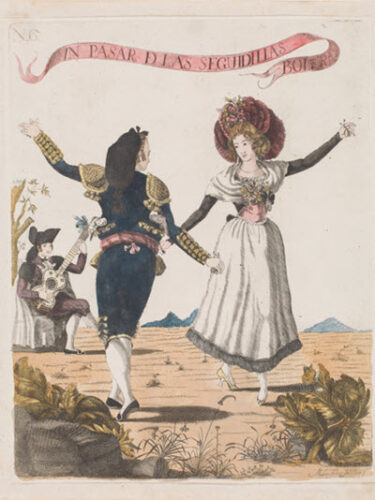

Referring to the dance numbers in the two Cecilias, Sànchez-Rojo introduces the “paradoxically traditional and modern” seguidillas that were wildly popular in the late 18th century. She talks us through the social commentary of their inclusion in the plays and “walks us through” their steps with explanations and beautiful illustrations from the time period by the painter Marcos Téllez Villar.

This is a book that will take hold of anyone interested in uncovering Spain’s fascinating modernization in the 18th century. It is sure to reward readers interested in learning (more) about Spain’s music and culture, both on the first read and on the many that are sure to follow.

Paul Murphy is Professor of Music at Muhlenberg College, where he teaches music theory, aural skills, and embodied music-making. He is co-author of The Musician’s Guide to Aural Skills, 5th ed. (W. W. Norton, 2026) with Joel Phillips, and José de Torres’s Treatise of 1736: General Rules for Accompanying (Indiana University Press, 2000). He has recently coauthored journal articles with Cristóbal García Gallardo for Eighteenth-Century Music and Music Theory Spectrum.