by Anne E. Johnson

Published June 16, 2025

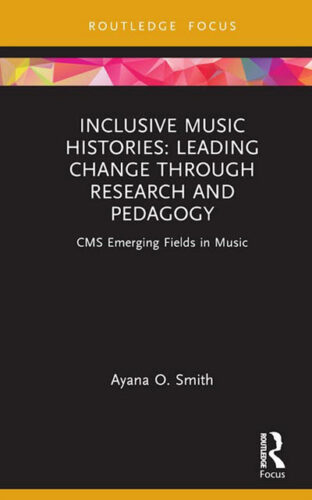

Inclusive Music Histories: Leading Change through Research and Pedagogy by Ayana O. Smith. CMS Emerging Fields in Music Series. Routledge, 2025.

Diversity. Equity. Inclusion. Against the current tide of power, Ayano O. Smith shouts for DEI at full volume in Inclusive Music Histories: Leading Change through Research and Pedagogy. But this is more than just an ivory-tower-bound theory of how change ought to work. Smith has tested her approach in her own classroom at the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, and wants everyone to try it.

Inclusive Music Histories is part of the CMS Emerging Fields in Music series, examining, among other things, “whose music matters.” True to that mandate, Smith not only questions the standard, conventional music history curriculum, she questions the well-meaning “fixes” that instructors tend to plug into that curriculum to make it more inclusive. Crucially, while criticizing those procedures, Smith offers logical, doable alternatives to help “create a truly intersectional music history narrative.” Adding, say, William Grant Still to the syllabus just to prove that there were Black composers further marginalizes him. Instead, Smith offers a comprehensive plan to discuss Still and the many styles he drew from. Teach Still because he was an important American composer.

The book’s detailed introduction thoroughly prepares the reader to absorb the complex plan of the next four chapters: “Identity in Historical Narratives”; “Representational Tropes in Text, Image, and Music”; “Caricature and Character, Appropriation and Authenticity”; and “Signifying Meaning in African-American Music.” While the chapters include helpful explanations of Smith’s motivation and thought processes, their true value is in their practical examples, “case studies” representing the way she has approached her own classes. Instructors wishing to build a viable university course would find their work half done by following Smith’s instructions to the letter.

But there will be resistance to this complete makeover. Smith acknowledges a core sticking point: How can instructors add more to an already packed schedule? Or what do we jettison to make room? “Diversity is not anathema to tradition,” Smith writes. “Even traditional subjects, such as early music, can be taught in diverse, ethical ways.” The key is to rethink not just what repertoire we teach, but why we are teaching it.

Take, for example, Rameau’s keyboard dance movement “Les Sauvages” from the Nouvelles Suites (1726–1727), which was inspired by American Indian dances. Smith challenges the reader to come up with a reason for teaching the work at all. If it’s just to cover the style and structure of the French keyboard suite, instead try some Élisabeth-Claude Jacquet de La Guerre. But Smith knows teachers can’t always avoid works because they are ethically difficult. We need to prepare students by exposing them to music that they’re likely to run into in the real world. But not without thought.

Smith never advocates for throwing out both baby and bathwater. While she recommends “de-centering” Gershwin by replacing Porgy and Bess with a unit on Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha, she doesn’t prevent an interested student from doing a project on the Gershwin opera, providing it considers the African American folk traditions he relied on. Expose students to the existence of other faiths besides Catholicism in Europe by teaching a lesson about Salamone Rossi along with Monteverdi. Keep the Guidonian Hand, but use a motet by a woman to analyze the presence of hexachords; Smith recommends one by Maddalena Casulana (fl. 1566-83). Sticking with Josquin? There’s a lesson plan for that: Compare the puzzles and symbolism in his polyphony to the similarly complex “mash-up” tracks by rap producer Danger Mouse.

Smith warns against common traps, such as claiming that “‘race’ as a modern concept did not exist” during the Baroque. Her approach to Handel’s Giulio Cesare spotlights the various levels of “othering” that can be found in Baroque opera through an examination of Cleopatra. One goal is to learn as much about ourselves (and our recent past) as we do about the composer’s own time.

As the early-music field broadens to include musics from outside the European tradition, Chapter 3, “Caricature and Character, Appropriation and Authenticity,” becomes ever more relevant. One project considers the music of Amy Beach and her borrowing (or appropriation) of Native American musical ideas, versus that of living Indigenous composer Brent Michael Davids.

Although Smith attempts to provide advice for teaching both undergraduates and grad students, the focus is on more advanced learners. Even the ideas for undergraduates are more sophisticated than many college students could handle. It would be useful to extend the class plans to include suggestions for music appreciation classes, where inexperienced students might be particularly receptive to a fresh approach.

The carefully considered lesson options give instructors a heads-up for all manner of issues that might arise. Yet having a plan differs from executing it with live humans. Smith admits that some students grow up in backgrounds that prevent them from seeing what’s wrong with how marginalized peoples are portrayed. She counters with a classroom rule: “Disagreements are not ever to be made in statements, but in questions,” encouraging discussion.

The only problematic suggestion from Smith, it seems, is that students do some of the unit work at home and use their completed notes or papers as a “ticket to enter” the class discussion. Surely a student who doesn’t finish an assignment will simply fall even farther behind if they’re not allowed into the room.

Each chapter includes exhaustive bibliographies and other recommendations for instructors interested in trying Smith’s ideas for themselves. And that, clearly, supports Smith’s central message: Don’t just think about DEI. Do it.

Anne E. Johnson is EMA Books Editor and frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently reviewed a gem of the Spanish Baroque, José de Nebra’s Venus y Adonis.