by Steven Silverman

Published August 27, 2023

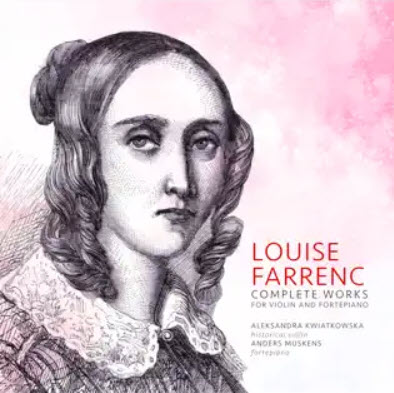

Louise Farrenc, Complete Works for Violin and Fortepiano, violinist Aleksandra Kwiatowska and fortepianist Anders Muskens. Leaf Music.

In liner notes for the first recording of Louise Farrenc’s complete works for violin and fortepiano on period instruments, Polish violinist Aleksandra Kwiatowska and Canadian fortepianist Anders Muskens spell out their approach: “We drew our inspirations from stylistic practices and the sound world of the past, and imagined how Farrenc might have performed this music together with violinist Joseph Joachim at the time of its premiere.”

Farrenc (1804-1875) lived an unusual life. Her pianistic talents were cultivated early, and she received training from notables including Hummel and Moscheles. At 15, she was allowed to audit Reicha’s composition classes at the Conservatoire, since women were not allowed to enroll as students. Surmounting gender biases, she was successful as a touring pianist, composer, and pedagogue — the first and only woman to hold a permanent position at the Paris Conservatoire in the 19th century (although she had to fight to receive pay equal to her male colleagues).

Born Louise Dumont, at 17 she married virtuoso flutist Aristide Farrenc. The couple toured together, and she resumed intensive study with Reicha. Her husband retired from the stage to start a music publishing business, which published most of her solo piano and chamber music. Unusual for the time, she taught 17th- and early 18th-century keyboard music, and first-of-a-kind investigation of early-music performance style.

Her compositions date from the 1820s through the early 1860s. There is a good bit of solo keyboard music (Robert Schumann praised an early set of variations) plus three symphonies (No. 3 is especially strong), and a great deal of chamber music, including music for unusual combinations: a Nonet (strings and winds, her most celebrated piece during her lifetime), a Sextet (woodwinds and piano), and piano trio with flute and cello. Missing from her oeuvre are the pieces in vogue in France during her lifetime — opera and salon music.

What her music does not sound like is French. Farrenc uses Viennese classic sonata form models consistently, almost as an algorithm. Within these classical models, her harmonic and melodic palette is early German Romantic. Mendelssohn is an evident influence (they studied with the same teacher, Moscheles), along with Mozart and Italian opera composers, notably Bellini. Max Bruch comes to mind as a similarly-styled composer. Swimming upstream, as a woman writing rather unfashionable music for the French public, she nonetheless received considerable recognition and esteem.

After her death, performances of her music ended, as happened with countless once-popular male composers whose legacy didn’t include an enduring masterpiece. In recent decades, interest in female composers led to Farrenc’s rediscovery and overdue revival.

On this new digital-only recording, violinist Kwiatowska and fortepianist Muskens presents her sonatas in C minor (1848) and A major (1850), and the earlier “Variations concertantes sur une mélodie Suisse” (1835).

Farrenc’s sonata-form movements are not quite cookie-cutter: expositions are a bit extended, with correspondingly shorter development sections. The C minor Sonata has a false recapitulation, the main theme returning softly in the tonic key before plunging back into its initial stormy atmosphere. The two slow movements, as well as the opening of the A major Sonata, are lovely and operatic — that sonata’s theme sings like a Bellini aria. Straight out of melodrama is the theme of the C minor Sonata finale, a rapid, ascending C minor arpeggio, with a rhythm that foreshadows the Libera me fugue of Verdi’s Requiem.

The sonatas and the Variations are true chamber music — each parts is of equal importance and the thematic material is distributed equitably between instruments. The keyboard writing is quite skillful, as one would expect from a virtuoso pianist, while the writing for violin, in the sonatas, is a bit more conventional, staying mostly in third position and lower. But there are also wonderfully idiomatic features, such as extended pizzicato accompaniment/quasi obligato in the finale of the C minor sonata, and octaves and double stops in parts of the A Major sonata.

In the sonatas, Farrenc’s harmonic language is conservative, showing little of the adventure of her contemporary Schumann, to say nothing of Chopin’s chromaticism. The Variations are in the variations brilliantes style so popular in the 1820s and 1830s: florid introduction, melodic rather than structural variations, an operatic slow variation, leading to a melodramatic bridge transition to a final variation where the violin gets to play up in the stratosphere.

Kwiatowska and Muskens give uniformly fine performances. They capture the music’s Romantic spirit, while also conveying its Classical-era structure. Their playing has plenty of nuance and temperament, and they aren’t afraid to take chances. Their vertiginous romp through the scherzo of the A Major sonata is one of many examples. Muskens digs into the keys to produce a rich melodic sound, agogic accents are well chosen and not overused, and passagework is well executed without sounding like an etude. Kwiatowska is a strong partner, sensitive to the vocal qualities of the writing, with lots of note-to-note variety while preserving the music’s line. And her octaves are impeccably in tune. The performances also have an appealing rhythmic flexibility which sounds natural and unmannered.

Their choice of instruments is interesting. Muskens plays an 1827 Brodmann Viennese fortepiano with all the pluses and minuses typical of Viennese instruments of that vintage: sweet sound, quick attack with rather rapid decay, somewhat hollow-sounding bass. Farrenc likely wrote for and played a Pleyel or Erard, the French pianos of the 1840s and 1850s — the same pianos for which Chopin composed. These instruments had iron bracing in the frame, straight stringing, and felt (rather than leather) hammers. They are more resonant than the Beethoven-Schubert era Viennese fortepianos. One would have thought a Pleyel/Erard style instrument more suitable for the repertoire, especially for the turbulent C minor Sonata. But Muskens plays so convincingly as to validate his choice, and, at least at the close range of a recording, he draws plenty of sound from the instrument.

Kwiatkowska plays a Georg Klotz violin from 1796 with the appropriate gut strings and a Baroque bow. She is quite sparing with vibrato, and, to my ears, her vibrato-less sound takes some getting used to. She finds plenty of subtle colors within that timbre and is ultimately convincing in her choices.

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York City and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 24nd season.