by Jacob Jahiel

Published April 26, 2025

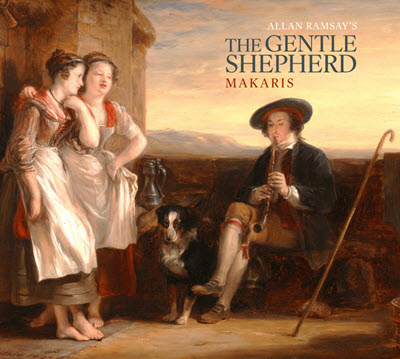

Allan Ramsay’s The Gentle Shepherd. Makaris. New Focus Recordings FCR924

For some, combining opera with banjo and Scottish bagpipe maketh the stuff of nightmares. For Makaris, the American ensemble specializing in Enlightenment-era music of Scotland and the British Isles, it makes for an excellent new album, The Gentle Shepherd, released last month on New Focus Recordings.

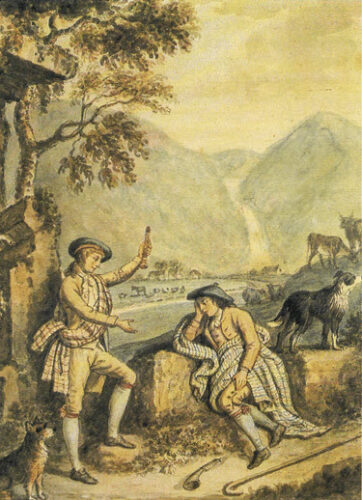

The album comprises the first complete recording of the 18th-century ballad opera by the same name, fashioned (not exactly composed in the strict sense of the word — more on that later) by Allan Ramsay (1686–1758), the Scottish wigmaker-turned-poet, playwright, impresario, and publisher. Ramsay’s literary accomplishments were many, but it is here where the bulk of his legacy remains: carved into a monument in Edinburgh’s Greyfriars Kirk are the words “For while your soul lives in the sky, Your GENTLE SHEPHERD ne’er can die.”

As a point of fact, it came fairly close. Obscurity eventually befell the once popular work that not only marked the first Scottish opera but, with an initial publication date of 1725, arguably represents the earliest example of a ballad opera — a genre mixing dialogue with popular tunes and styles, typically set to original text. (Regarding the use of arguably, the genre’s best-known English-language example, John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, was published in 1728, but was the first to reach the stage.)

Rescuing The Gentle Shepherd from disrepair requires feats of scholarship as much as musicianship. Editions from Ramsay’s lifetime include only the name of a popular tune next to its corresponding text, necessitating the parsing of later editions (some of which provide texted melodies or bass lines, but also inflict unwelcome changes), chasing after titles that were in constant flux, picking from numerous variants of a melody, and settling on issues of instrumentation and harmony.

As cellist Kivie Cahn-Lipman and fiddler Caitlin Hedge write in the liner notes, “Our specific choices were guided primarily by a sense of fun. When offered multiple plausible options for any tune in the opera, we generally picked the most idiosyncratic, choosing harmonic surprises over what many in Ramsay’s own time (and our own) might have considered good taste.”

Musically, Makaris’s album is great fun — look to Sang XVa, “Jocky said to Jenny,” for a dram of comedy — but I’ll even argue for its good taste. The singing is consistently excellent: o’er sweet for Handel, perhaps, but perfectly suited to this repertoire.

Corey Shotwell’s dulcet tenor immediately endears the earnest Patie, our gentle shepherd and protagonist. With perfect diction and evident musical imagination, Fiona Gillespie neatly invokes the caprices of Peggy (Patie’s love interest and the most emotionally interesting of the bunch), most touchingly in Sang XVII, “Woes my heart.” Tenor Bradley King (Sir William Worthy) anchors the drama with the gravitas and poise. So charming is the narration by David ‘Jock’ Nicol that you wish for him to read both your grocery list and your eulogy.

The band, too, plays more than a supporting role; it is in the instrumentals where the opera’s folk elements jostle about with idioms from parlor music and Italianate opera seria, all to great effect. Caitlin Hedge, a Baroque violinist and violist whose accolades include first-prizes from Scottish fiddle competitions, bridges these styles seamlessly and without artifice — look to the two tunes by O’Carolan concluding Act II. Surprising harmonies and delightful ornaments spill from the fingers of harpsichordist Eliott Figg, harpist Tracy Cowart (who also sings Symon), and theorbo/guitar/banjo player extraordinaire Paul Morton. Ben Matus (Bauldy, bagpipe, Irish whistle), Sian Ricketts (recorder, oboe, stock-and-horn), and Gillespie (also on Irish whistle) prove a nimble and witty bunch. Cellist Kivie Cahn-Lipman gives a spirited delivery of a tune by famed Italian cellist Lorenzo Bocchi, one of the album’s several instrumental “insertions.” Doug Balliett, in addition to top-notch bass playing, breaks out the elusive tromba marina.

If “The Scottish Play” is unlucky, then this first Scottish opera must surely be the opposite: charming, funny, and exuding good fortune — all things a good pastoral ought to be. And speaking of good fortune, the words etched on Ramsay’s monument, at least for now, hold true: The Gentle Shepherd lives on, enlivened by this skillful and resourceful troupe of musicians.

Jacob Jahiel is a writer and viola da gamba player living in Baltimore. For EMA, he recently wrote about performance- vs. scholarship-heavy approaches to early-music higher education.