by Anne E. Johnson

Published November 17, 2025

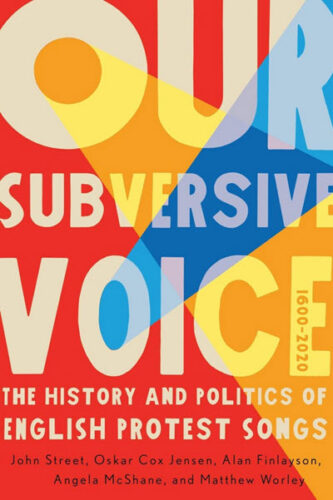

Our Subversive Voice: The History and Politics of English Protest Songs, 1600–2020. John Street, Oskar Cox Jensen, Alan Finlayson, Angela McShane, and Matthew Worley. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2025. 312 pages.

The word “collective” occurs frequently in Our Subversive Voice: The History and Politics of English Protest Songs, 1600–2020. Indeed, the concept of group action permeates the project, all the way to the listing of its five author/editors as a unified team. Each of the six topical essays is ascribed to all of them, a rare approach in academic publishing. Their combined knowledge and the astonishing depths of detailed research amassed here have resulted in a groundbreaking book and deluxe website that shine a light on a genre that badly needed the attention.

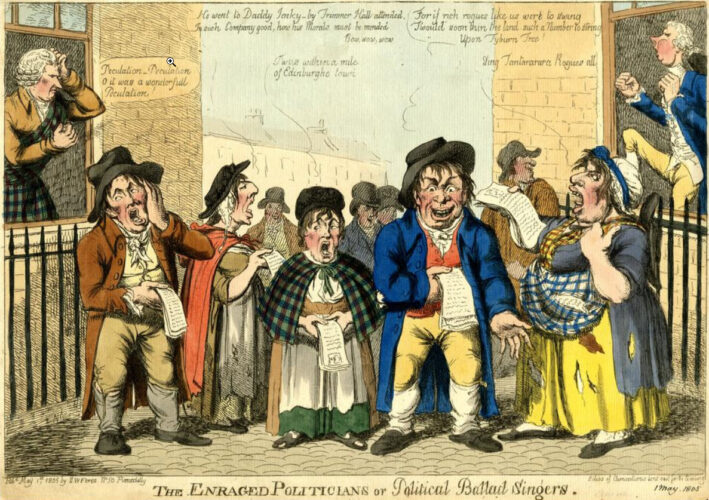

The authors focus on three main points of misunderstanding about English-language protest songs. First, they are usually thought to belong only to the 20th and 21st centuries, yet they go back much further in time. Second, protest songs are mainly associated only with the U.S., although Britain has an even longer history of them. Third, they are rarely taken seriously for their content despite being a form of political communication as worthy of study as speeches, pamphlets, and other historical evidence. Every one of these corrections is argued convincingly and with copious song examples.

Those examples are pulled from a list of 750 English songs, covering 1600 to 2020, that the authors deemed protest songs. And while they insist repeatedly that their categorizations are subjective, they carefully define “protest song” as an umbrella term. Crucially, it must be more than a list of grievances: “A protest song, like protest itself, is intent upon political change — of ideas, attitudes, or actions.”

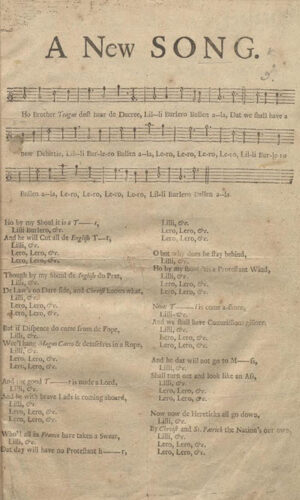

All sides of protest are considered. Most of the chosen songs have what would today be considered a liberal bent — anti-slavery verses, or workers seeking equal pay and better treatment, for example. Yet the authors set forth a long exposition on the huge impact of the 1686 “A New Irish Song – Lil-li bur Lero”: It was written by three frustrated gentlemen complaining privately about the pro-Catholic bias they felt under King James II, then it grew in popularity until it helped chase him from the throne.

There’s plenty more to engage the early-music aficionado, giving a rarely encountered on-the-ground political context to musical eras that can seem rarified and separate from societal realities. An especially fascinating example are the songs by John Freeth (1731-1808). His choice to self-publish rather than use a licensed publisher, plus the fact that he was a tavern-owner and could therefore provide a safe haven for like-minded thinkers, allowed him to produce more and gutsier songs than others of his time. The book details in the severity of punishment for those accused of protesting through song — it changes throughout time, being worst in the early centuries. Yet Freeth once managed to publish a verse hinting at regicide.

The book’s exhaustive examination is divided into six chapters. “Protest (and) Song’s Long History” illustrates how protest songs are neither a static concept nor specifically American. The authors explain their choice of historical starting point: At the turn into the 17th century, England saw a quick growth in the popular music trade, which had a major impact on the distribution of all songs, including those in the “protest” category. The range of topics for early protest songs include “threats to Protestantism, whether at home or abroad; the ravages of plague; shortages of food; and the intense political protests that led up to civil war, regicide, republican government, restoration, plots, crises, and ‘glorious’ revolution.”

Chapter 2 views protest song as vehicles for political theory. “Songs are less expressions of political ideas than symptoms of a societal order about which we are usually encouraged not to think very much,” suggest the authors, citing Earnest Jones’ 1852 “Song of the Lower Classes”:

We’re not too low – the grain to grow

But too low the bread to eat

We’re far too low to vote the tax

But we’re not too low to pay

The deft use of multiple disciplines in this study are on display in the discussion of rhetoric in Chapter 3, emphasizing the history of philosophy. Unfortunately, actual music is perhaps the least present of those disciplines, with very few musical details in the book more complex than mentioning “some simple devices such as repetition, a chorus that repeats the theme.”

A consideration of social and economic contexts for protest songs occupies Chapter 4. The authors consider the issue of representation. By what rights, if any, is the composer or singer an expert or authority on the topic they’re protesting? What stake does the audience have in changing the topic of complaint? Chapter 5 then dives into the means of production and distribution of these songs, from hand-scrawled verses to high-quality, bound printed tomes, and then the modern physical and digital platforms for recorded sound. The final chapter deals with censorship and the many direct and indirect means that governments have used over the centuries to suppress what they consider to be threatening songs.

As one would expect, the English Industrial Revolution in the 19th century gave birth to some poignant and rebellious songs in support of factory workers. Just as interesting are examples from the punk movement in the late 1970s and early ’80s (the band Crass, in particular — not as familiar to most American readers as their fellow rebels, the Sex Pistols). Latter-day examples include Lowkey’s “Ghosts of Grenfell” from 2017 and the Black Lives Matter-inspired “We Live Here,” written by Bob Vylan in 2020.

Even if they hadn’t applied their research to writing this book, the scholars would still have made a major contribution to song study by creating oursubversivevoice.com. It contains basic information, lyrics, and (where possible) a link to a recording for all 750 songs. The book refers to those songs; the digital version links to them. This is one book where it’s worth going electronic.

Anne E. Johnson is EMA Books Editor and frequent contributor to Classical Voice North America. She teaches music theory, ear training, and composition geared toward Irish trad musicians at the Irish Arts Center in New York and on her website, IrishMusicTeacher.com. For EMA, she recently wrote about the ‘Child Ballads’ and American folk song.