by Lois Rosow

Published September 14, 2025

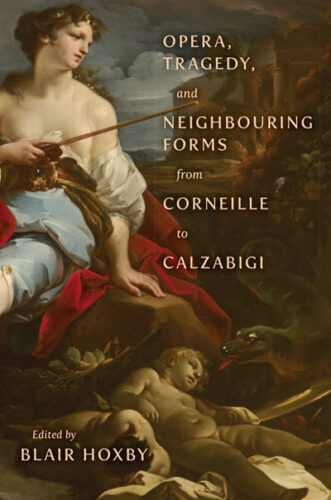

Opera, Tragedy, and Neighbouring Forms from Corneille to Calzabigi, edited by Blair Hoxby. University of Toronto Press, 2024. 336 pages.

Opera, Tragedy, and Neighbouring Forms from Corneille to Calzabigi focuses on the interplay of spoken tragedy and opera in 17th- and 18th-century practice and criticism. As editor Blair Hoxby explains, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, critics treated opera and spoken tragedy as unrelated. This book, he writes, “returns us to a world in which opera and tragedy remained on intimate terms.”

The authors of the 10 chapters are specialists in languages and literature, theater history, and classics; one is a musicologist. They have produced a fascinating collection of case studies.

The chronological starting point is the work of the French playwright Pierre Corneille, especially the critical debate over his play Le Cid (1637), which resulted in the codification of the rules of French tragedy — rules that resonated throughout Europe for over a century.

The first chapter, by Hélène Visentin, focuses on one of the “neighboring forms” alluded to in the book’s title: the tragédie en machines. Here, French spoken plays were embellished with the stage machinery of Italian opera, creating dazzling scenic effects, all while the rules of tragedy (or, when appropriate, Ovidian fable) were scrupulously observed.

In 1673 Jean-Baptiste Lully introduced the tragédie en musique, an operatic genre laden with supernatural spectacle and dance. Here the rules of tragedy applied, but differently: Much appeared onstage that was forbidden in the spoken theater. Hoxby, in his own chapter, focuses not on Lully’s works but on Médée (1693), a tragédie en musique by composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier and librettist Thomas Corneille, which he finds interesting both for its complex reading of the ancient playwright Euripides and as an experiment in gloom, horror, and terror. (Hoxby, I think, is too quick to discount Lully’s ability to move audiences to pity and fear.)

In the last of the three chapters focused on France, Downing Thomas considers the 18th-century playwright Voltaire, who borrowed tactics from the tragédie en musique for heightened visual and poetic effect in his spoken tragedies, even while retaining the moral aims of tragic poetry.

Just as the debate over Corneille’s Le Cid was a flashpoint in the history of tragedy, so the work of the Arcadian Academy in Rome, founded in 1690, was a flashpoint in the history of Italian opera: a rejection of the emotionally intense and sensual literary style then dominant in Italy, in favor of restrained models, either pastoral or tragic. These developments would lead eventually to 18th-century opera seria, culminating in the heroic librettos of Pietro Metastasio. Stefanie Tcharos’s chapter concerns the early, experimental phase of this reform movement, as represented by Alessandro Scarlatti’s opera La Rosaura (1690). Commissioned for a dynastic wedding, the work deftly combines a sentimental suitor in the pastoral mold with a female protagonist who models the virtuous honor of a tragic heroine.

The next three chapters concern instances of opera seria. Francesca Savoia analyzes the first libretto for the Italian public theater by a female author: Agide re di Sparta (1724) by Luisa Bergalli, a protégée of Apostolo Zeno. Bergalli fused Aristotelian poetics and Cartesian ethics to tell a feminist story, and like Metastasio she used exit arias strategically for the development of characters. Enrico Zucchi highlights the political content of Metastasio’s librettos, a rejection of the absolutism that gave unlimited power to the prince, favoring the enlightened absolutism of a sovereign who respects the law and offers clemency to his people. Finally, Tatiana Korneeva examines two imperial Russian adaptations of Metastasio’s La Clemenza di Tito. In each case the resulting opera allegorized the political realities of the Russian imperial court.

Robert Ketterer’s chapter concerns a pasticcio by George Frederick Handel. Handel created Oreste (1734) by borrowing arias from his previously composed operas — a calculated commercial decision, as he competed with another troupe in London. He relied not only on the audience’s familiarity with that music but on their familiarity with the story of Orestes — not from any translation of the original Greek tragedy by Euripides but from its many theatrical adaptations, well known to Londoners. The chapter by Pervinca Rista offers one more “neighboring form”: the dramma giocoso, in which serious, comic, and “mixed” characters interact in realistic settings. Most of us know this model from Lorenzo Da Ponte’s libretto for Mozart’s Don Giovanni. Rista focuses instead on the mid-century originator of the genre, Carlo Goldoni.

In Magnus Tessing Schneider’s chapter we encounter the chronological endpoint of the collection: Ranieri Calzabigi’s Ipermestra o Le Danaidi, a tragedia per musica from 1778–84. Calzabigi had already challenged Metastasio’s hegemony in his earlier “reform” librettos written in collaboration with Christoph Willibald Gluck. Now he intensified that challenge by seeking to revive the tradition of the ancient Greek tragedian Aeschylus in this terrifying story of revenge and group massacre (the latter carried out in a sort of Dionysian frenzy), marked also by the title character’s moral defiance of tyrannical authority. Metastasio had told a refined version of this myth, entirely eliminating its murderous elements. Schneider describes Calzabigi’s version as permeated by “bloodthirsty intoxication” and considers the widely varied critical responses it received. In short: A century and a half after Corneille, decorum was still an issue.

By highlighting quarrels, debates, and poetic preoccupations with genre, this collection illuminates an important period of European theater history.

Lois Rosow is a musicologist specializing in French opera of the 17th and 18th centuries. Her most recent article, in the collection The Fashioning of French Opera (1672–1791): Identity, Production, Networks (Brepols, 2023), concerns work the music copyists of the Paris Opéra did for the French royal court. She is currently editor-in-chief of the Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music.