by Pierre Ruhe

Published August 19, 2025

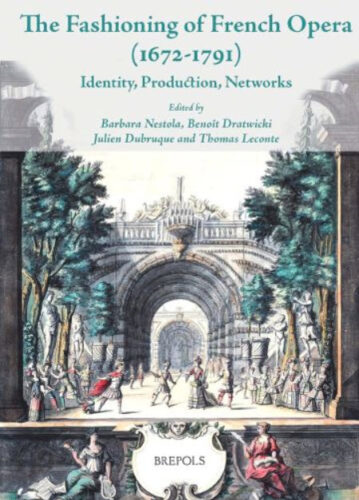

The Fashioning of French Opera (1672-1791): Identity, Production, Networks, edited by Barbara Nestola, Benoît Dratwicki, Julien Dubruque, and Thomas Leconte. Brepols, 440 pages.

The Académie Royale de Musique was ‘a workshop where everyone influenced each other…This is an almost ideal example of tradition building.’

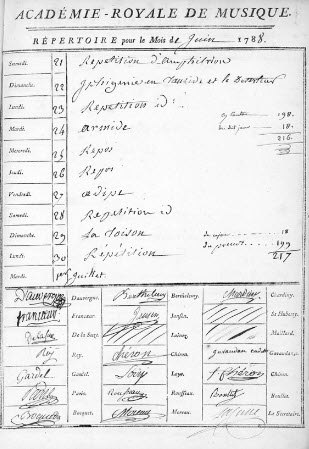

In The Fashioning of French Opera (1672-1791): Identity, Production, Networks, the research-based Centre de musique baroque de Versailles (CMBV) commissioned some 30 essays, all of them in English, focusing on the hothouse institution named the Académie royale de musique — where “poets and composers did not merely write operas, they wrote for the Opéra, thus collaborating with a for-profit cultural institution.”

Notably, the essays do not dwell on composers and librettists — the only true creators from our Romanticized perspective — but focus instead on the processes and people who brought operas to the stage, from directors, administrators, and financiers to the craftsmen who constructed scenery, the costume designers, and the choreographers who lifted courtly dances to fine art. Performers sit high in this hierarchy. Composers and librettists are there, of course, although in many cases music was added or removed according to the production revival and a text might have started with one author but was often a group (re)creation. Such a perspective means that a work can no longer be considered sui generis — the book’s overarching aim.

From the start, this collaborative art form was part of a “prestige strategy,” writes co-editor Thomas Leconte. The music Académie, like similar efforts for painting, literature, and the sciences, followed Louis XIV’s vision to create “official models and canons that glorified the royal image while simultaneously celebrating and spreading ‘French excellence.’ Their collective goal was thus to create a true national identity.”

Rather than risk organic and uncontrollable developments in opera, in March 1672, the king granted Jean-Baptiste Lully alone a kingdom-wide monopoly on performances that combined singing (in French or Italian) with dancing and instrumental music. The owner of this royal privilege, which was passed down, sold, and re-sold after Lully’s death, meant they could also run schools to train singers, dancers, and instrumentalists, and could charge admission to help cover costs. After Lully, the opera’s finances were forever mismanaged.

In recent years, as once-obscure gems have been studied, performed, and recorded — Colin de Blamont’s Le Caprice d’Érato, Élisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre’s Céphale et Procris, Jean-Philippe Rameau’s Achante et Céphise, and dozens more — the old refrain that “ancient régime opera was propaganda as a branch of government” has given way to a more interesting exploration of how artists responded to political pressure to survive and sometimes thrive. Since it’s opera, all the relevant creators reacted in their own messy, non-linear way. (An inexact and more menacing parallel: there’s a hefty literature on the music and lives of Shostakovich and Prokofiev; there’s also in-depth research on the Soviet system that tried to control them.)

As CMBV Artistic Director Benoît Dratwicki writes, “the opera-making progress was deliberately controlled, so we might assume that it was authoritarian. In reality, it was structured around complex back-and-forth and power-counterpower relationships, such that we must rethink the very concepts of ‘author’ and ‘work.’”

A more interesting exploration of how the arts responded to political pressure to survive and sometimes thrive

Julien Dubruque, in his chapter “The Members of the Petit Chœur Between Lully and Rameau,” uses the musicians from the continuo team to neatly articulate this idea. In the decades between those two paradigm-setting composers, about two-thirds of all works created at the Opéra were by performers or administrators from within the institution, of varying skill and inspiration. It was largely an in-house operation, where a “common spirit, a house style, was first forged by practice and by emulation rather than by an intellectual imitation of a Lullian canon.” When we loop in audience expectation for familiarity, especially with regards to the clarity of language in the recitatives, and political pressure to glorify the monarchy, we could say the sounds and styles became standardized.

“The impression of familiarity, if not uniformity, that the modern listener gets” from lyrical works from the first half of the 18th century “is not by accident,” Dubruque writes. It was “not an academy of music theoreticians but a workshop where everyone influenced each other and was influenced by the revivals of works written by their glorious predecessors. This is an almost ideal example of tradition building.” This is a rather anti-modernist perspective: instead of focusing on innovation and the newness of each work or production — with originality an end in itself — the book makes a case for formulas and relative stasis that, rewardingly, built up a company.

Thus chapters on seemingly dry topics — such as Lola Salem’s “Regulating Singers’ Pensions at the Opéra” — offers insights on the development of the genre as a whole, where an artist or administrator was eligible to receive a pension after 15 years of service. Although by the mid-1700s itinerant Italian ensembles were booming in popularity, their cheap-to-produce model offered no financial stability for anyone involved. But as the Italians threatened the artistic hegemony of the Opéra, the latter’s bureaucratic stability was able to retain French talent: “the long-term effects on creativity that have not yet been fully gauged by scholars.”

The Fashioning of French Opera boasts an international roster of scholars and, by design, touches on many recondite facets of the Académie. Thomas Vernet tracks the creation of the tragédie en musique, a noble genre and royal entertainment “whose symbolic power would be able to resist the evolution of the sphere of opera.” Graham Sadler discusses the surprisingly belated rise of the maître de musique, the music director role that today seems so fundamental to the coherent operation of an opera company. Co-editor Barbara Nestola explores how singers added airs to a work as a means of self-promotion. Three chapters, from three different approaches, find insights on the collective creation of libretti.

As much as music, dance was an essential element of French Baroque opera. In “Ballet Masters at Work, 1672-1764,” Rebecca Harris-Warrick and Laura Naudeix explore how these maîtres de ballets were salaried employees (unlike composers and librettists, paid a commission per opera). Research has shown that although some of the steps were common to the ballroom — the menuet, gavotte, and so on — these dances on stage were more elaborate, requiring greater technique and larger floor plans. (And, unlike many historically informed productions today, there was generally no dancing while singers were singing.)

In fascinating chapters on visual depictions of members of the Académie troupe, Gregoire Ichou and Jean-Michel Vinciguerra connect the massive cultural influence of the opera with the new-found vogue for portrait paintings. Once women were permitted to dance on stage, in 1681, interest in these graceful artists led to a boom for their images, often touching on the erotic with bare arms, legs, and feet, and an uncovered breast. Notably, they write, “we know that at this time no dancer of the Opéra could appear onstage wearing a light tunic revealing part of her anatomy” since stagewear consisted of hoop skirts, gloves, and low-heeled pumps. These portraits were the start of female celebrity culture, at once adulating and stereotyping.

As far back as 1741, the Opéra was tracing its own history, mythologizing its foundations and growth. By 1778, André-Earnest Grétry’s Les Trois Âges de l’opéra signals that they knew the golden days of Lully and Rameau were over and a third age was emerging. If the basic outline is well known — relative stasis between Lully and Rameau, followed by the reforms of Gluck — the details are themselves absorbing.

Like most histories we read, these essays de-politicize decisions and effects that were originally purely political in nature. And courtly institutions were typically driven by internal dynamics as well as royal imperatives. Yet in our own politically trumpy era — with a presidential takeover at the Kennedy Center, threats against academia and the Smithsonian, the decimation of government arts and humanities funding — Pauline LeMaigre-Gaffier’s chapter “From Gift to Mutualized Management: the Menus-Plaisirs at the Service of the Académie Royal de Musique” reads as an alarm call. Under Louis XIV, the monarchy exerted control of the major performing arts institutions using the instrument of the Menus-Plaisirs, an administrative network to standardize the arts and literature and integrate them into political and legal institutions. For the arts, what started as “informal implications” evolved into “reinforced monarchical control over Parisian spectacles.”

In all, this compelling collection succeeds in opening fresh perspectives not yet adequately explored, and with broad implications. Sylvie Bouissou writes on the directors of the Opéra, all men with connections to the world of high finance if not themselves personally rich. Still, despite the prerogative to flatter the king and keep the Académie royale de musique financially solvent, the directors’ priorities haven’t much changed across the centuries: “artistic engagement, the magic of performance, and something unique to opera” when the arts are combined on stage.

Pierre Ruhe is publications director of Early Music America.