by Thomas May

Published September 21, 2025

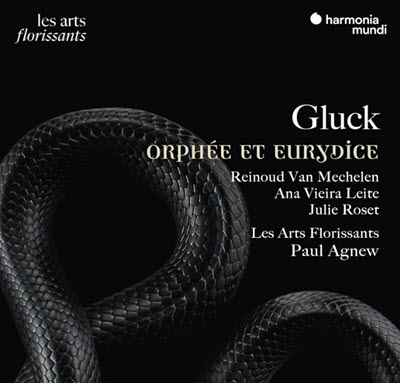

Gluck: Orphée et Eurydice. Les Arts Florissants and soloists, conducted by Paul Agnew. Harmonia Mundi HAF890540102

What a delight to come upon Les Arts Florissants’s latest recording, Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice. As coincidence would have it, I’d just experienced their performance of another Orpheus story on stage at the Lucerne Festival this summer: Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s La descente d’Orphée aux enfers, led by the ensemble’s founder, William Christie. Charpentier’s exquisite tragédie en musique breaks off mid-story, with Orpheus still in the Underworld and Eurydice’s fate unresolved. In its fragmentary state, Charpentier’s 1686 opera captures the stark tragedy of the myth: a descent without resolution.

Where Charpentier leaves us suspended in darkness, Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice brings the story to radiant closure. All of these variants are rooted in the image of music’s power to transcend even the ultimate limits of life and death. Orpheus’s rescue mission to retrieve Eurydice from the Underworld, after all, provided the founding myth of opera itself. But in Gluck’s treatment, the familiar tale becomes a new kind of origin story — one that not only streamlines the myth but rethinks the art form in the process.

When Gluck first set the story in his 1762 Vienna version as Orfeo ed Euridice, he broke decisively with the rigid formulas and decorative excess of late-Baroque opera, creating a streamlined, dramatically focused work that became the cornerstone of his reform ideals. Those ideals were famously codified in the preface to Alceste (1767), where Gluck declared his aim to make music serve the poetry and drama rather than mere vocal display.

By the early 1770s, Gluck’s reputation had spread beyond Vienna — thanks in no small part to his former pupil, Marie Antoinette. When she became Dauphine of France, she championed his music, helping secure him an invitation to compose for the prestigious Paris Opéra. Paris offered Gluck a stage of unmatched scale and resources, along with a sophisticated audience steeped in its own operatic traditions.

Twelve years after the original Orfeo, he seized the opportunity to rework the opera for this new context, and the transformation went much further. With its freshly composed recitatives, expanded ballets, and a title role rewritten for haute-contre tenor rather than castrato, the Paris Orphée et Eurydice of 1774 recast the very identity of the work, forging a daring synthesis of Italian lyricism and French theatrical grandeur — a hybrid that opened new possibilities for opera.

From the start, Gluck and his librettist Ranieri de’ Calzabigi streamlined the drama to its essence: just three characters and a chorus, with no prelude showing Orphée and Eurydice’s former happiness, no exchanges with Pluto and Prosperpina. We are thrust directly into tragedy. It’s opera by Occam’s razor, and the immediacy is searing.

For the Paris version, Gluck worked with the poet Pierre-Louis Moline, who reshaped Calzabigi’s text to suit French theatrical traditions and tastes. As Denis Morrier explains in his fine booklet essay, the 1774 Paris score is rethought from the ground up, with four new arias, expanded orchestral and ballet numbers, substantially reworked recitatives, and a modernized orchestration (with clarinets).

These changes gave the opera a distinctly French character — especially in its emphasis on ballet and declamation — while preserving the radical dramatic clarity that Gluck and Calzabigi had achieved in Vienna. “What Gluck produced, faced with such challenges, is in reality a new work,” writes conductor Paul Agnew, “an immense transformation both in ambition and style created to convince his new French public of his legitimacy.” This version became a sensation, performed 47 times in its first season — a rare feat for the era — and established Gluck as a central figure on the Parisian stage.

The opera opens with a chorus of shepherds and nymphs voicing their communal grief in dark, flowing harmonies. From within this collective mourning, Orphée’s solitary cries emerge with piercing intensity, drawing us into his private torment. Les Arts Florissants’s chorus is superb, each voice clearly individuated yet blending into a collective force.

Gluck treats the chorus as a fully-fledged dramatic character: at times consoling, at others obstructing or celebrating. That dual role becomes crucial in the famous second-act confrontation with the Furies. Here, two soundworlds collide: the brutal, stabbing chords of the Underworld guardians versus Orphée’s tender, pleading song. Reinoud Van Mechelen’s voice seems to embody art itself, confronting raw violence with beauty. The moment encapsulates Gluck’s reformist vision — music not for display but for dramatic truth.

The orchestral ensemble matches the singers in eloquence. The instrumental solos are given with as much humanity and expressiveness as any aria. In Act I, the recitative “Eurydice, Eurydice! De ce doux nom” and the air “Plein de trouble et d’effroi” feature an exquisite dialogue with the oboe, whose plaintively echoing lines seem to breathe alongside the singer.

Later, when Orphée reaches the Elysian Fields, Gabrielle Rubio’s solo flute ushers us into an otherworldly calm with phrasing tenderly sculpted against a veil of strings. Here and throughout the opera, Gluck avoids the Baroque rhetorical tradition of “word painting.” Instead, as Denis Morrier observes, “he adorns the opera with a continuous orchestral discourse whose aim is to underline the context rather than the text, to depict emotional affects, and even to articulate what human language cannot express.”

The contrast between Orphée’s lyricism and the Furies’ ferocity shows Gluck’s modernity. His aesthetic has been pigeonholed by the composer’s own phrase as “noble simplicity,” but this should not be mistaken for austerity. Occasional bursts of coloratura are purposeful, dramatizing states of agitation or hope rather than providing vocal display for its own sake. This clarity of means gives the music its timeless power.

The casting is ideal for this focused drama. Van Mechelen takes on the demanding role of Orphée with extraordinary artistry and his haute-contre voice anchors the performance with diction so crystalline that every syllable carries meaning. His singing traverses a wide emotional spectrum, from heroic defiance to heart-wrenching fragility. It doesn’t sound effortless — nor should it. You hear the very strain of longing and grief in his phrasing, a physical embodiment of Orphée’s agonizing loss.

Julie Roset brings a pristine radiance — at times sounding curiously angelic — to the role of Amour, her bright soprano a foil to the slightly more weighty warmth of Eurydice, sung by Ana Vieira Leite. Though Eurydice appears only in the final act, her arc is compressed and intense: from initial joy to bewilderment, anguish, and death. Leite’s singing makes every turn of emotion register vividly. When the trio of voices finally blends in the closing scene, the effect is cathartic, a hard-won release from suffering.

Agnew and his players excel in the ballet sequences, which are not merely decorative but central to the Paris version. The conductor points to their dramatic and scene-setting function, “painting with vivid colors the various tableaux, from Orphée’s first pleading at the gates of the Underworld to the calm tranquility of Parnassus.” The celebrated “Dance of the Blessed Spirits” in Act II provides the clearest example, embodying a moment where Gluck deepens the drama through pure instrumental poetry as Orphée crosses into the Elysian Fields. The deceptive plainness of Gluck’s writing is elevated by the performers’ jeweler’s-loupe precision.

After the final trio and chorus, Gluck provides an extended ballet suite that functions more as a festive epilogue. On disc, such sequences often risk anticlimax, but here they emerge as surprisingly vivid and celebratory, a radiant affirmation of life that balances the opera’s opening grief.

Not least, this project offers a corrective to the dominance of the Italian version in modern performance. By presenting the 1774 Paris score — recorded in July 2024 at the Cathédrale Notre-Dame du Liban in Paris — Agnew and Les Arts Florissants remind us how Gluck tailored his reforms to specific cultural contexts. Having introduced his concept of the Orpheus and Eurydice archetype in Vienna, the composer went further in Paris to align his work with Enlightenment ideals of clarity and universality. Listening today, we can hear why this version caused a sensation nearly 250 years ago.

Thomas May is a writer, critic, educator, and translator whose work appears in the New York Times, Gramophone, Strings, and other publications. Lucerne Festival’s English-language editor, he is also U.S. correspondent for The Strad and program annotator for the Ojai Festival and Los Angeles Master Chorale. A frequent contributor to EMA, he recently spoke with conductor Grete Pedersen.