by Emily Thelen

Published March 13, 2023

Saint Cecilia in the Renaissance: The Emergence of a Musical Icon by John A. Rice. University of Chicago Press, 2022. 384 pages.

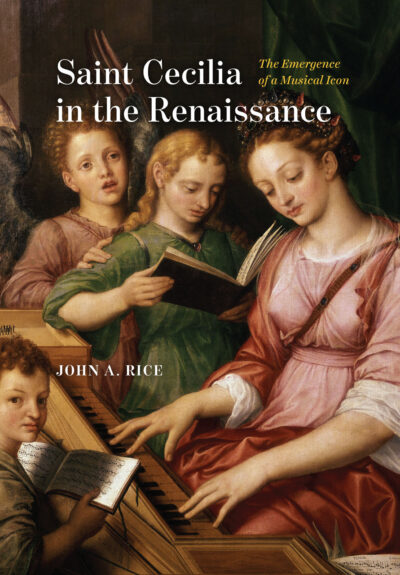

Saint Cecilia, an early Christian martyr, is famous for being the musician’s saint. From artistic depictions of her playing instruments to musical societies and festivals named in her honor, St. Cecilia’s association with music has a rich and very long history. Some musicians might be disappointed to learn, however, that there is no historical evidence of her actually being a musician. Yet the story of how she gained her status as patron of music and as a musician herself is fascinating.

John Rice’s new book is a brilliant accounting of how the exchange between art, music, and liturgy shaped the saint’s identity. Through an extensive survey of visual representations and liturgical celebrations, Rice shows that St. Cecilia’s patronage of music has its roots both in the liturgy and an evolving iconographic tradition.

John Rice’s new book is a brilliant accounting of how the exchange between art, music, and liturgy shaped the saint’s identity. Through an extensive survey of visual representations and liturgical celebrations, Rice shows that St. Cecilia’s patronage of music has its roots both in the liturgy and an evolving iconographic tradition.

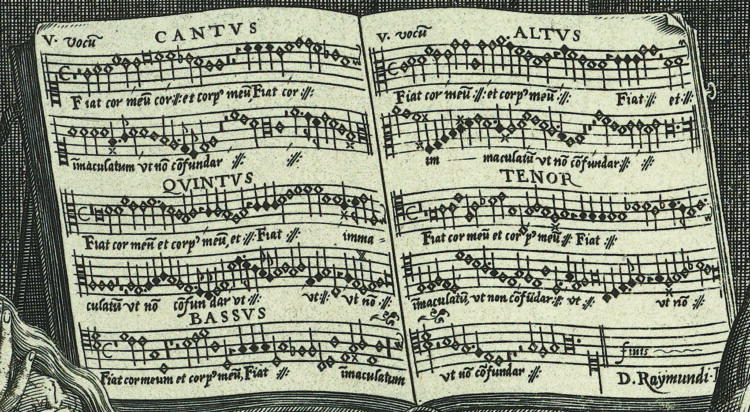

The seed of her association with music grew from a 5th-century account of her wedding, in which Cecilia promised her virginity to God: “While the instruments sang, she sang in her heart to the Lord alone, saying ‘Let my body and my heart be made pure, that I may not be confounded.’”

These lines were chosen for several antiphons of the Medieval liturgy and would later serve as the texts of numerous 16th-century motets. Early artistic renderings of this passage portray St. Cecilia at her wedding banquet, not yet as a musician herself, but with musicians playing instruments such as the organ.

When St. Cecilia was depicted at a wedding banquet, she was easily identifiable. Yet when portrayed among a group of saints, she was not distinguishable from any other virgin martyr. In the late 15th century, artists took the organ from the wedding portrayals and adopted it as her emblem, painting a small portative organ by her hands or feet. Interestingly, the organ depicted was often unplayable—missing bellows or having the pipes in the wrong order—and St. Cecilia was shown next to but not playing it. Throughout the 16th century, however, artists took a further step and painted her playing the keyboard of increasingly larger instruments, often assisted by angels pumping the bellows.

Rice has identified the key factor that elevated St. Cecilia from a musician to the patron of music: her popularity in the confraternity culture of the Low Countries. Confraternities and guilds of musicians, seeing St. Cecilia portrayed with an organ, chose her as the patron saint of their organizations in the 16th century. Singers in many Flemish cities were awarded gifts of money, wine, and food on her feast day, November 22. The musicians themselves celebrated with a banquet, and two cities in northern France even held musical competitions for the occasion. Rice suggests that St. Cecilia’s popularity had as much if not more to do with the musicians’ desire to celebrate their own craft and receive gifts than with honoring the saint.

The proliferation of Cecilian motets by leading 16th-century Franco-Flemish composers further cements Rice’s argument that St. Cecilia’s cult had its first flowering in the Low Countries. The court of Charles V appears to have had a particular interest in her. Thomas Crecquillon of the imperial chapel, for instance, composed five Cecilian motets, more than he did for any other saint. Inspired by artistic depictions of St. Cecilia as a musician, composers returned the favor by writing Cecilian motets specifically for works of art.

Rice’s choice for her most emblematic image is the one that graces the book’s cover: Michiel Coxcie’s painting of St. Cecilia at the virginal, accompanying angels singing a Clemens non Papa motet. Despite her Roman origins, the musicians’ cult of St. Cecilia spread from Northern Europe to Italy only in the late 16th century. Rice devotes the last portion of his book to her popularity in Rome, which culminated in a 12-voice Mass for St. Cecilia by Palestrina and his colleagues.

Upon opening Rice’s book, one is immediately drawn to the stunning collection of 73 color plates that illustrate the evolution of ideas surrounding St. Cecilia. A feast for the eyes, this book within a book catalogues the transformation of St. Cecilia from virgin martyr to musician. For the performer looking to sing music for St. Cecilia, Rice has compiled an extensive appendix of 170 pieces published before 1620.

The book is broadly accessible to historians and musicians. Rice, an independent scholar, takes particular care to write for the non-specialist when discussing liturgy. He includes numerous contemporary accounts and has a keen eye for the amusing human quirks manifested in these documents. Rice’s book stands as a consummate example of the interactions between art, music, liturgy, and confraternity culture and how these exchanges enliven and spur on the formation of a saint’s identity.

Emily Thelen is a musicologist who writes about music and Marian devotion in the Low Countries. Her recent publication, A Choirbook for the Seven Sorrows: Royal Library of Belgium MS. 215-16, is the second volume of the new Leuven Library of Music in Facsimile Series.