by Steven Silverman

Published May 13, 2024

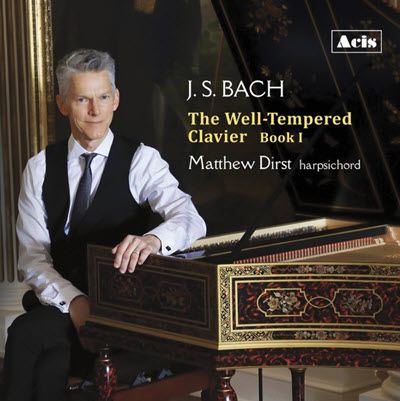

J.S. Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1. Matthew Dirst, harpsichord. Acis Productions APL 54117

For many performers and composers, J.S. Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier — 48 preludes and fugues divided into two books and covering all of the major and minor keys — is at the apex of the keyboard pantheon.

Matthew Dirst’s new recording of the WTC Book 1, from 1722, is a praise-worthy addition to the recorded repertoire. These are straightforward, no-nonsense readings, technically impeccable (left-hand trills are especially good — indistinguishable from right-hand trills), with nice clarity of voicing.

Dirst, artistic director of the period-instrument ensemble Ars Lyrica Houston, is also a noted organist and Bach scholar. On this recording, he plays a 2021 harpsichord by John Phillips from Berkeley, inspired by instruments from Dresden’s Gräbner family in the early 18th century.

In Dirst’s hands, especially eloquent are three of the preludes with a tragic dimension, those in C-sharp minor, E-flat minor (which sounds like a first cousin to the exquisite soprano aria “Aus liebe will mein Heiland sterben” from the St. Matthew Passion), and B-flat minor.

His readings are full of sentiment but avoid sentimentality, capturing the music’s dignity and pathos. As Dirst explains in his liner notes, “the Book 1 preludes and fugues summon a variety of private moods.”

Note the subtle variety of differentiating speed of the rolled chord accompaniment in the E-flat minor Prelude as a means of unobtrusively keeping the music going forward. The G minor Prelude also comes off very well. Dirst plays it a bit faster than one often hears, which nicely avoids the cloying trap some performers fall into.

The great extended fugues — in C-sharp minor, D-sharp minor, and (especially) B minor — all get sympathetic readings. These hold together wonderfully, with clearly delineated points of structural demarcation (for example at measure 18 of the B minor Fugue or measure 61 of the D-sharp minor Fugue), and with subtle use of inegale in the running passagework (in the C-sharp minor and B minor fugues).

Many of the shorter fugues tend to be martial-sounding. This results both from brisk tempos, aggressive registrations (two eights with a more than occasional addition of the 4-foot stop as well), and (generally) a single affect per fugue. The martial approach works well for some of the fugues, like the C Major, the French overture in D Major, and the G minor. However, I hear some of the fugues, like the C-sharp Major and G Major, as being more dancelike and humorous. I might also suggest that initial statements of fugue subjects need not be played precisely in time. The C-sharp minor initial entry, for example, gains in mysteriousness and expressivity if played slightly out of time.

Dirst is sparing with his ornamentation, generally only adding the occasional cadential trill. An exception is on the repeats of the B minor Prelude, where the performer appropriately adds a variety of well-chosen ornaments. Registrations are also on the conservative side, with the notable and effective exception of using the buff (lute) stop for the lovely F-sharp Major Prelude.

Bach famously noted that the WTC is “for the profit and use of musical youth desirous of learning.” Some of Dirst’s readings, to my ears, hew to this message a bit too much, coming off as etudes. But Bach went on to say that the WTC is “especially for the pastime of those already skilled in this study” — these are not merely teaching pieces. His D Major, G Major, F Major, and D minor preludes were thus on the didactic side for my taste and a bit undeviating rhythmically — although, to be fair, there is some subtle variety in rhythm and articulation patterns in the D Major. Dirst largely avoids it, but I would suggest that staggering (not playing the hands precisely together) could be used more. At times, this might add to the expressivity a prelude like the G-sharp minor at mm. 19-21. Staggering would likewise help the clarity of the D-sharp minor Fugue, at mm. 36-38, while helping protect the inverted fugue statement in the alto.

Dirst uses a Neidhardt temperament for the recording, adding that he made “discrete adjustments” to the temperament, depending on particular keys. Not only does the temperament work very well, but the tweaking per key is apparently consistent with Bach’s own practice as described in the earliest biographies of Marpurg and Kirnberger.

Altogether, a fine rendition of Bach’s towering compendium. Recommended indeed!

Steven Silverman is a pianist and harpsichordist whose performances include concerts at Weill Hall in New York City and the Salle Cortot in Paris. He and his wife, the violinist and violist Nina Falk, are co-founders of the Arcovoce Chamber Ensemble, now in its 25th season. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed revolutionary Beethoven on the fortepiano.