by Jeffrey Baxter

Published May 9, 2025

‘A level of choral singing that matches, if not exceeds, some of the best from early-music ensembles’

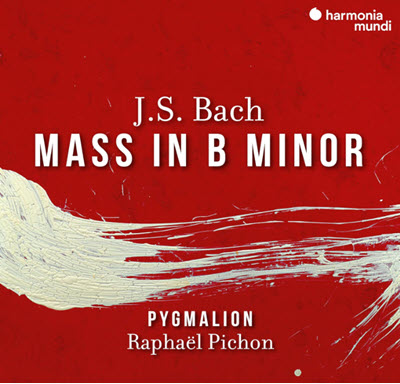

J.S. Bach: Mass in B minor Pygmalion, soprano Julie Roset, mezzo-soprano Beth Taylor, alto Lucile Richardot, tenor Emiliano Gonzalez Toro, bass-baritone Christian Immler, conducted by Raphaël Pichon. Harmonia Mundi HMM902754.55

Pygmalion, the period-instrument ensemble founded by French conductor Raphaël Pichon in 2006, has garnered much attention recently, including some unusual “immersive” endeavors such as semi-staged versions of the Monteverdi Vespers and Mozart Requiem, and a Brahms Requiem set in a Nazi-era submarine base, with the choir roaming the audience. They have recorded Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony with extracts of his stage works and interpolations from Weber and Schumann.

In interviews, Pinchon has spoken of the artist’s responsibility to refresh masterpieces “but from a different angle,” and that we’re living in a time “when technologies offer promise and perils alike.” More traditionally, he has also led Pygmalion in a series of lauded Bach recordings, including the Motets and the Matthew-Passion.

Their most recent work is a May 2025 release of Bach’s great summa opus, the B-minor Mass, a recording that, while commendable, is nothing revelatory. What it does display is a level of choral singing that matches, if not exceeds, some of the best from “early music” ensembles.

One of the delights in this recording is Pichon’s purely choral approach, with no concerto grosso or soli/tutti touches, and no one-to-a-part singing. While a choral-focused performance might seem old fashioned by contemporary standards for a specialized group like Pygmalion, the advantage and beauty are in the talent and virtuosity of this 30-voice chorus, given here in four parts [12-6-6-6] — large enough to handle the divisi required in the 8-part double chorus Osanna, the 6-voice Sanctus, and the many SSATB movements scored for five voices. Their balance of agility and fire-power is a great asset, as evidenced in many moments like the Et resurrexit, where Pichon has all the basses sing the impressive unison virtuoso solo line, “et iterum venturus est” to great dramatic effect.

As for the orchestra, Pichon has assembled an ensemble of 16 strings [5-5-3-2-1], with solo winds, brass, timpani, and an additional viola da gamba for continuo. They play with decisive accuracy and verve, and — as a bonus, with some of the clearest (and exciting) timpani-strokes to punctuate tutti cadences.

The five vocal soloists are notable for their full-throated yet stylistic approach. Mezzo-soprano Beth Taylor has her perfectly even vocal registers on full display in “Laudamus te.” Tenor Emiliano Gonzalez Toro’s impressive instrument, sensitively handled, never overpowers but always delivers. Bass-baritone Christian Immler lends a commanding Voice-of-God presence in both his arias.

Much credit goes to Pichon for his continuo choices, employing instruments both plucked (theorbo and harpsichord) and sustained (organ), though sometimes the organ’s fussy right-hand figuration, played on a 2-foot stop, seems intrusive in the Credo’s opening measures.

In the Gloria section, they add the harpsichord in the aria “Quoniam to solus sanctus,” a musical setting of “the Most High” by the lowest instrumental and vocal forces, heroically declaimed by bass Immler. The percussive quality of the plucking strings of the harpsichord help clarify the texture of all these low-pitched instruments.

Pichon’s use of the audibly plucking theorbo to accompany the pizzicato bass line and solo flute in the Domine Deus gives a great clarity of texture, as well as contrast. Similarly, its sensitive use in the Benedictus delicately evokes the introspective hollowness of the sparse 3-voice texture of solo flute, tenor, and basso continuo.

The biggest disappointment is Pichon’s penchant for overly slow adagio tempi, as evidenced in the opening, glacial, Kyrie introduction. Similarly, the “Qui tollis peccata mundi” and “et incarnatus est” movements lag in energy, recalling a romantic approach from a different time. At certain points — as in the delay of the final syllable “-est,” of “et se-pul-tus est” in the Crucifixus, or the completely out-of-context adagio at the end of “Et expect resurrectionem” begin to sound like Pichon luxuriating in his chorus’s beauty of tone as in many an Eric Whitacre-style a cappella piece.

The choice of such slow tempi seems overstated, given what surrounds them: many of the preceding and succeeding quick tempi end up sounding faster than they really are, thus sounding off-kilter. One example is Pichon’s relaxed “et in terra pax” which does not quite match the hemiola in the preceding Gloria that sets up this tempo precisely. It is close but proves slightly out of proportion — something Bach took great care of when he was assembling and re-creating his Mass from its pre-existing movements and earlier compositions.

Pichon provides moments of great beauty — as in the famous Crucifixus — given in an aggressive, slightly quick tempo, with accented bow-strokes evoking the hammering of nails into human flesh. The chorus’s doleful sostenuto lines float above, in anguished beauty. Equally stunning is the breathtaking whirlwind end to “et expecto resurrectionem,” where the movement builds to a crashing energetic close (on “Amen”), with no hint of rallentando.

One odd choice near the end, however, is the whispered, opening intonation of the repeat of the Osanna movement. Is this some kind of surprised response to the Benedictus? We’re all for refreshing great works “from a different angle,” as Pinchon says, but this comes across as jarring and distracting, as well as somewhat hokey. Fortunately, the finale of “Dona nobis pacem” is gloriously paced, from its understated (piano) beginning to a triumphant end.

There is much to admire in this recording, with its talented performers’ skillful technique and passion on display. However, I look forward to future Pygmalion projects that might go beyond the scope of the core repertoire, with the hope that such a fine ensemble might continue to bring great treasures to light that, in fact, need a spotlight shined on them.

Jeffrey Baxter is a retired choral administrator of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, where he managed and sang in its all-volunteer chorus and was an assistant to Robert Shaw. He holds a doctorate in choral music from The College-Conservatory of Music of the University of Cincinnati and has written for BACH – The Journal of the Riemenschneider Bach Institute, The Choral Journal, and ArtsATL. For Early Music America, he recently reviewed Bach’s Easter Oratorio and Magnificat.