by Karen M. Cook

Published June 6, 2025

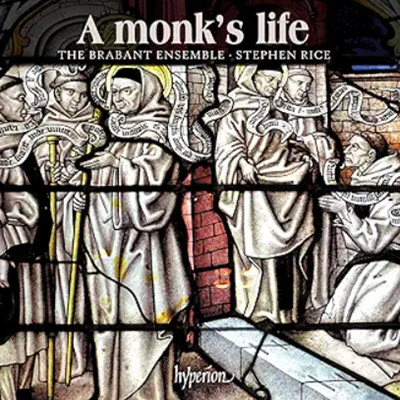

A Monk’s Life. The Brabant Ensemble, conducted by Stephen Rice. Hyperion CDA68447

The Brabant Ensemble, led by Stephen Rice, is a familiar name to any lover of Renaissance polyphony. Their lengthy discography has earned many an accolade over the ensemble’s almost 30-year tenure on the early-music scene, especially for its frequent focus on the lesser-known composers of the 16th century. Their 2024 release A Monk’s Life, on the British Hyperion label, continues this trend with aplomb, as fully half of its 30 works are by less recognizable composers.

The central conceit of the album is quite compelling. In her excellent liner notes, Barbara Eichner (who, along with conductor Rice, prepared the editions used for this recording) reveals that the album is as its title proclaims: an imagined journey through the religious life, and death, of a monk in post-Reformation Germany. After the Council of Trent, monks in German-speaking lands were challenged to “contribute to the religious regeneration of the Catholic Church,” as Eichner puts it, and their days, years, and lives were measured out as much by music as by anything else. As such, the album is divided up into six of the most significant or consistent moments of such a monk’s religious life: entering monastic life, praying the Divine Hours, eating and drinking, celebrating Mass for the first time, being ordained as Abbot, and dying and hopefully ascending to Heaven.

The album opens with Orlando di Lasso’s radiant “Sponsa Dei,” a contrafact of a work honoring Emperor Maximilian II’s coronation. In keeping with his renown as the most prolific composer of his day, Lasso is well represented here; his harmonically audacious motet “Quis rutilat Triadis?” helps to conclude the recording, while his Missa super Veni in hortum meum, surely an under-recorded gem, forms the backbone of the central “first Mass” section.

A few other recognizable names also appear. Motets by Jacob Regnart, Clemens non Papa, and Cipriano de Rore (a treat, given the prominence of his madrigals) are sprinkled throughout, while a contrafact of a dance song by Giacomo Gastoldi, “Wer wollt den Wein nid lieben?,” celebrates the delights of wine.

Wine notwithstanding, the real delights here are the works by the lesser-known composers. The soaring upper voices in Christian Erbach’s “Deus in adiutorium” are lovely against the warmth of the lower parts, while the beautiful imitative opening of Jacob Reiner’s “Veni creator spiritus” leads into some marvelous polyphony throughout. Text painting abounds in Bernhard Klingenstein’s “De vita religiosa,” perhaps most obviously in the striking tempo contrasts at “cadit rarius, surgit velocius.” The ensemble saved the best for last, though, as the album concludes with Sebastian Ertel’s stunning “Aeterno laudanda choro,” which speaks of joining the heavenly choir.

The organization and theme of the album is really quite engaging, and the choice of repertory is marvelous. I wish, though, that they might have considered singing the Gastoldi with a smaller ensemble; given its non-liturgical enthusiasm for bibation, smaller forces might have set that work apart as something the monks might have enjoyed singing “after hours,” so to speak. A meditation: how might such a story resonate differently (which does not imply better) with an all-male ensemble, reflecting our monk and his brethren? Such queries aside, it’s an excellent album, one that rewards the intellect, the imagination, and the musical senses in equal measure. I hope they might take it upon themselves to continue their exploration of this literature in the near future.

Karen M. Cook is associate professor of music history at the University of Hartford. She specializes in late-medieval music theory and notation, focusing on developments in rhythmic duration. She also maintains a primary interest in musical medievalism in contemporary media, particularly video games. For EMA, she recently reviewed the Binchois Consort reconstructing lost Jacob Obrecht partbooks.