by Sophie Genevieve Lowe

Published July 12, 2025

Academia de Música Antigua de Medellín is one of a few schools in Latin America that teaches historical performance.

In a brilliant partnership, the inaugural Latin American Congress on Baroque Luthiery will help supply the Academia with new instruments.

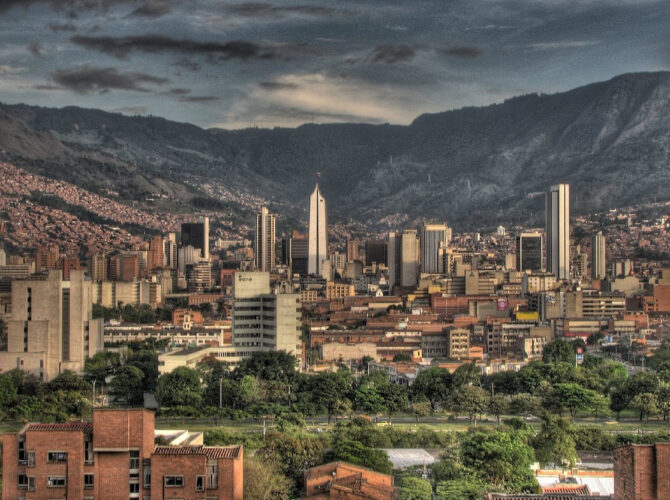

Nestled in the Aburrá Valley within the Andes mountains lies the city of Medellín, known as Colombia’s “City of Eternal Spring.” The area was long occupied by Indigenous peoples before European settlements were established in the 17th century. Although the city has had an infamously troubled past, Medellín today is an emblem of metamorphosis — a city of cultural renaissance and chic tourism, fueled by an overwhelmingly youthful population. This cultural synthesis integrates into an eclectic music scene, from salsa and electronica to, most recently, early music and historical performance.

In 2016, sensing a new global hotspot, Vogue published an article titled “21 Reasons the Cool Kids of Colombia Flock to Medellín.”

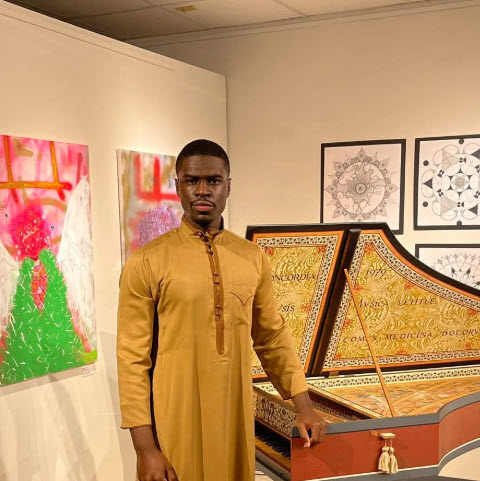

And it was here in 2021 that David Esteban Escobar, a Case Western Reserve University alum, founded the Academia de Música Antigua de Medellín, an independent music school and one of the few in Latin America that educates students in historical performance.

“The cultural mix of Indigenous, African, and European heritages create a fertile ground for new expressions,” explains Esteban, speaking of his native city, “making Medellín not only a center of Colombian identity, but a meeting point of global perspectives. For projects like the Academia de Música Antigua, this spirit of openness and ambition makes Medellín an ideal place to grow.”

All the components necessary to curate a high calibre “Academy of Early Music” in Medellín are in place — although the students still need instruments. Esteban and New York-based Mexican luthier Gabriela Guadalajara devised a brilliant solution. (For this unique project, the Academy recently collected a prestigious EMA 2025 Engagement Award.)

The cultural mix of Indigenous, African, and European heritage creates fertile ground for new expression, making Medellín a center of Colombian identity and a meeting point of a global project.

First a little background. Esteban says that the Academia was “born out of necessity, as an urgent response to the lack of structured, high-level training in historical performance in Latin America.” While many institutions in Europe and North America have well-established historically informed performance [HIP] programs, Esteban says that schools in Latin America have “no ability to integrate it meaningfully into their curriculum, preventing students from acquiring the fundamental tools required to engage with early music at an international level.”

Currently, there are around 30 students in the Academia de Música Antigua, most of them attending local colleges who are majoring in modern instruments or voice. The Academia curriculum is robust, with students developing skills in varied styles from Renaissance improvisation to colonial-era villancicos.

The Academia has a core commitment to educational equity and thus provides full tuition. A requirement of all students is that they take private lessons. Violin, cello, gamba, traverso, trumpet, and plucked instruments have access to in-person lessons. Zoom allows for remote studies, including harpsichord lessons from a teacher in Portugal and violin lessons from Guillermo Salas, who lives in Ohio.

In addition to weekly lessons, the school holds workshops led by various esteemed musicians, many from North America. Harpsichordist Webb Wiggins, living in Washington D.C., has traveled on multiple trips to South America to teach. (This project is full of connections: Wiggins was one of Esteban’s teachers at Oberlin.)

When Wiggins heard that the Academia was losing access to a harpsichord, Esteban recalls, “he jumped in and sent me the receipt of the new instrument he had just bought in Germany!” Wiggins speaks of the students’ talent: “There is obviously a love of early music there. I was moved to tears upon hearing the male voices singing an impromptu performance.”

Last year, Salas led the Academia in a concert of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and Rebel’s The Elements, which included students from Paraguay and Chile. Esteban is keen to ensure that every new project is rooted in scholarship. “In that sense,” Salas says, “the Academia is the true heir of the Humanist origins of the Renaissance accademie.”

‘It was my first time traveling outside my country… my first time engaging with different cultures and languages’

The Academia’s impact is starting to ripple across both South and North America. Cellist Irene Micaela Henao was introduced to historical performance by Esteban, and her studies at the Academia enabled her to attend the Tafelmusik Baroque Summer Institute in 2024, funded in part by an EMA workshop scholarship. “It was my first time traveling outside my country,” Henao says, “my first time playing alongside more cellists than just myself, my first time seeing so many historical instruments I had only read about, and my first time engaging with different cultures and languages.”

Instruments as a Fundamental Right

In addition to providing high-caliber training and full tuition, the school is dedicated to providing professional-level instruments for its students. The Academia has in its collection violins, lutes, recorders, traversos, and trumpets, although most of the instruments are on loan. Yet Latin America’s growing interest in historical performance has been stymied by the lack of historical instruments. Esteban believes that “access to high-quality historical instruments should not be a privilege but a fundamental right for anyone seeking serious training in HIP.”

Herein lies the predicament, that eternal problem: talented musicians needing instruments that facilitate artistic and technical growth. At this point of the story we find a true hero, luthier Gabriela Guadalajara. (Besides her many wonderful instruments, readers may have also ordered strings from her online shop, Gabriela’s Baroque.)

Esteban and Guadalajara first met at the Boston Early Music Festival. Esteban had been ordering strings from Gabriela’s website and started asking about aspects of Baroque set-up for instruments. Years later, a violinist named Felipe Giraldo was studying with the Academia. An aspiring luthier, he had many questions, and Guadalajara delighted in sending pictures, templates, and measurements of instruments. Guadalajara became fascinated with the project and “felt like we were on the same page.”

Initially, the Academia asked if young Giraldo could relocate to NYC as an apprentice, but Guadalajara did not have room in her atelier. She asked if she could travel to them instead. Esteban exclaimed, “We were waiting for you to say that!”

Although Guadalajara’s first teaching trip was intense, both the luthier and the Academia director realized that they were only scratching the surface. Guadalajara donated her time and expertise and used her network to mobilize resources. “We feel that there is the need for a closer connection between instrument makers and musicians,” she says, “even more so when we talk about Baroque style since not all the instrument makers are involved in this kind of work.”

This dream will come true in the inaugural Congreso Latinoamericano de Laudería Barroca (or Latin American Congress on Baroque Luthiery), to be held in October, 2025.

For this first conference, eight participants from Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico will study in Medellín with Guadalajara for an intensive two-week workshop. The class will instruct luthiers to hone their skills to produce instruments in the style of 18th-century masters. For her part, Guadalajara relishes the chance to invest in other luthiers in the way she began her own training at New York’s William Monical & Son.

“Having a project like the conference allows me to share and continue passing on my knowledge and experience to keep alive the tradition,” Guadalajara says. “It’s incredibly rewarding when you have the enthusiasm, the curiosity, the energy, and willingness to learn that I felt in my first visit to Medellín.”

The instruments crafted during this conference will be added to the academy’s collection for future students

The magnitude of this violin making conference cannot be overstated, as the instruments crafted during this conference will be added to the academy’s collection for future students. These new violins will help ensure a new generation of early-music performers in Latin America. And the Academia has already designed a blueprint to replicate the conference each year in a different Latin American country, with the next potential conference in Mexico in 2026.

The Baroque Ecosystem

The Baroque wave is spreading across Latin America, with projects such as Bolivia’s Festival de Música Barroca, known as “Misione de Chiquitos,” and the Festival del Barroco Latinoamericano in Perú. “Music and instrument-making are interconnected disciplines,” says Guadalajara. “They should go hand in hand, and there is the need for creating an ecosystem that allows musicians to have well-made instruments they can afford, made in our countries, instead of having to import them from the U.S. or Europe. One of the Academia’s goals is to connect music and instrument making as we all learn together. This is a long-term project, obviously, but we have to start somehow.”

Bolivian violinist Karin Cuéllar Rendón, incoming artistic director of the Misione de Chiquitos Festival (and currently EMA board president), calls the upcoming Laudería Barroca conference “an important milestone not only for the Academia, but for the rest of Latin America, as this model can be replicated in other countries, contributing in this way to the expansion of early-music scenes in Latin America.”

Speaking of the trailblazing nature of the conference, Salas surmises, “This kind of project is nothing short of a miracle and is deserving of protection.” The potential of historical performance and instruments from Latin America is a dazzling new era in our field. And if Vogue were to write an updated article, the title might now read, “21 Reasons the HIP Kids of Colombia Flock to Medellín.”

UPDATE June 20: Since the publication of this article, Gabriela Guadalajara informs us that the Conference will now be held in Bogota and 10 aspiring luthiers with participate.

Sophie Genevieve Lowe, a Baroque violinist, is artistic director of Bruton Baroque and member of pianoforte trio Assai Ad Libitum. She lives in Williamsburg, Va., with her husband, Baroque cellist Ryan Lowe.