by Jacob Jahiel

Published October 5, 2025

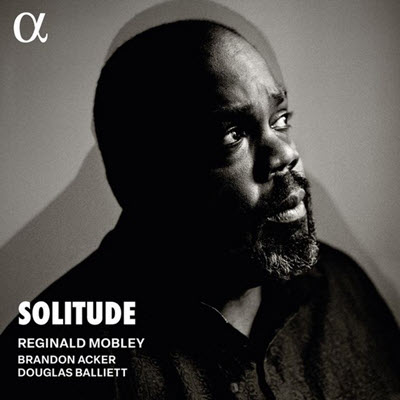

Solitude. Countertenor Reginald Mobley, lutenist Brandon Acker, and bassist Doug Balliett. Alpha Classics, ALPHA 1161

By now, Reginald Mobley can hardly be described as a rising star in the world of early music. The American countertenor’s career has spanned multiple continents and garnered numerous accolades. In showbiz terms, he’s “made it.” Mobley’s debut album, Because (2023), received rave reviews from many listeners as “a powerful portrait addressing the musical legacy of Black spirituals.” Just two years later, he returns with Solitude, an equally alluring album officially released Oct. 3 on Alpha Classics.

In the album’s liner notes, Mobley decries our current age of tech-driven superficiality, but celebrates music’s ability to intervene via the “…power of stories themselves. To focus on such power through the lens of English song, a combination as simple as a voice, a lute, and a viola da gamba can pause the world and create an intimate space. A space unplugged from the busy world around us where emotion, feeling, meaning, and imagery created by stories reign unopposed.”

The choice of repertoire lends itself well to such a mission, offering a mix of the ultra-familiar and seldom (or never) heard. Representing the former category are top-of-the-charts tunes like Henry Purcell’s “Music for a While” and John Dowland’s “Flow My Tears.” Other selections are further afield, like the music of Samuel Pepys (1633–1703), best remembered for his meticulously detailed London diaries, and a chunk of 19th-century American music by guitarist, composer, and civil rights activist Justin Holland (1819–1887). There is, too, a healthy dose of new music by Doug Balliett (b.1982, a bassist and co-collaborator on the album) and Jonathan Woody (b.1983).

It’s easy to understand why Mobley has amassed such a strong following. His voice, an almost flute-like instrument, somehow surpasses the typical binaries one makes when speaking of singers: warmth and brightness, transparency and substance, sensitivity and strength. Moreover, his deep musicality compliments his knack for storytelling. In Dowland’s “Sorrow, Stay,” Mobley evokes a special kind of passion that, paradoxically, can only be properly articulated through quiet restraint. So, too, can he embrace sentimentality without being overly cloying, as with the wonderfully lyrical ballad by Henry Clay Work and Justin Holland, “The Ship that Never Returned,” that concludes the album.

Mobley is supported by theorbist and lutenist Brandon Acker and double bassist and viol player Balliett, flexible and sensitive musicians whose presence in this intimate sonic space comes frequently into the sonic foreground. Acker’s sense of long line rivals that of his vocalist, and Balliett may well be the only bowed bass player I know whose pizzicato bass lines don’t feel like self-conscious, like a gimmick.

It’s not totally clear what any of the above has to do with solitude (beyond the Purcell title), but one might imagine that Mobley is encouraging us to eschew our Instagram stories in favor of the real stories these songs convey, redirecting our ever-shrinking attention to the pathos this music might internally provoke. In the wake of the pandemic, solitude represented lamentable isolation. Perhaps we ought to learn to appreciate it again.

Jacob Jahiel is a writer and viola da gamba player pursuing a doctorate in historical musicology at the University of Pennsylvania. For EMA, he recently profiled the intriguing singer-composer Rebecca Scout Nelson.