by Rebecca Cypess

Published March 7, 2022

In 1773, the Viennese composer Marianna Martines (1744–1812) became the first woman inducted into the famed Accademia filarmonica of Bologna. In 1779, the Roman composer Maria Rosa Coccia (1759–1833) became the second woman granted this honor. The career trajectories of these women mirrored one another in some ways, and they may even have been in brief and indirect correspondence.

Yet while Martines’s social fortunes rose considerably over the course of her lifetime and she came to be almost universally celebrated in Vienna and abroad for her musicianship and respected for her admirable character, Coccia was not so lucky. Despite having attained an education in music and having achieved short-lived fame and recognition for her skill, Coccia was attacked by other musicians who apparently viewed her as a professional threat and derided her for seeking public attention.

What factors led to the dramatic difference in the ways Martines and Coccia were perceived during their lifetimes? Few women had access to an education in composition at all, and women’s authorship often rendered them subjects of scrutiny and derision. At a moment when women’s role in public life was contested and restricted by both formal and informal means, how did Martines protect her public reputation, while Coccia’s suffered?

A number of factors contributed to the differences between Martines and Coccia, many of them outside Coccia’s control. Among these were their family situations, connections in the musical and artistic world, the type of music they chose to publish, and the ways in which they framed themselves in the public sphere.

Drawing on her connections and particular circumstances, Martines was able to attract the attention of the public, exercising agency in the shaping of her musical environment, without appearing to transgress the social norms that prevented women’s full participation in public life. Coccia lacked such social and musical connections, and, as she sought a professional career that placed her more squarely in the public eye, her fortunes suffered as a result.

A ‘Dilettante’ Out of the Public Eye

Anna Catherina Martines, later Marianna Martines, was born in Vienna on May 4, 1744. Her Spanish grandfather had moved to Naples, where her father, Nicolo Martines, was born; Nicolo left Naples for Vienna, where he worked as maestro di camera for the papal nuncio. In Vienna, the family became closely associated with the imperial court poet Pietro Metastasio, who would become the leading operatic librettist of the 18th century. Metastasio and the Martines family resided together in a single apartment from 1734 or 1735 until the poet’s death in 1782, together with Nicolo’s wife, Maria Theresia, and children. In other floors of the same building—the Altes Michaelerhaus at Kohlmarkt 11—lived Nicola Porpora, who may have taught Marianna singing, and a young Franz Joseph Haydn, whom she would cite as her keyboard teacher.

Recounting her education and her musical development in a letter to Padre Martini, Martines explained that she had been born with natural talent for music but that she had augmented that inborn musicianship with diligent study. “In my seventh year they began to introduce me to the study of music, for which they believed me inclined by nature,” she wrote to Martini. “My exercise has been, and still is, to combine the continual daily practice of composing with study and scrutiny of that which has been written by the most celebrated masters.”

She cited composers from the preceding generations—Handel, Jommelli, Caldara, and others—whose works she had studied carefully. And she noted that she had learned the art of counterpoint, which required extensive training of the sort not often available to women, with Giuseppe Bonno, who had himself studied with the great Neapolitan masters Francesco Durante and Leonardo Leo.

Nor did Martines stop at the diligent study of music: “Persuaded, then, that, in order to prevail in music, I would need still other fields of knowledge; thus, aside from my natural languages, German and Italian, I undertook to familiarize myself with French and English, in order to be able to read the great poets and prose writers.” Beyond music and letters, Martines gained a general aesthetic education from her close connection to Metastasio: “In all my studies, the chief planner and director was always, and still is, Signor Abbate Metastasio who, with the paternal care he takes of me and of all my numerous family, renders an exemplary return for the incorruptible friendship and tireless support which my good father lent him up until the very last days of his life.”

In this letter, then, Martines carefully positions herself for her readers: She drew on the gifts of nature and augmented them through diligent study. For a woman to admit to such exertion in learning was itself noteworthy, since hard work was often considered unseemly for women with upper-class pretentions. This admission of labor might have been more acceptable in Vienna; even though the imperial city was Catholic, it was under the influence of the work-ethic of Protestant lands. Still, Martines’ autobiography would likely have required the adoption of a certain sprezzatura (noble grace and carelessness) in other respects. She accomplished this by remaining largely out of the public eye.

During the 1760s and 1770s, Martines became highly regarded as a composer, keyboardist, and singer, attracting the notice of international critics and performers, despite the fact that she rarely published her compositions or appeared in public performances. Through her close connection to Metastasio, she came to perform for the Empress Maria Theresa and her daughters. However, Martines’ primary site of performance was her family’s home. It was there that Charles Burney met her in 1772 while he was visiting Vienna to gather material for his General History of Music. He spent several evenings in the company of Metastasio and Martines, reporting in effusive terms on her performances of keyboard sonatas and arias she self-accompanied at the harpsichord. Her surviving musical manuscripts, which include Italian cantatas (all set to texts by Metastasio), Latin motets, orchestral pieces, keyboard concertos, and other genres indicate that she often wrote for larger ensembles, including strings and various combinations of oboes, flutes, and horns. She performed these larger pieces, too, in her family home.

In Vienna, hosting social-musical gatherings such as these was already a relatively common practice. Such gatherings were often referred to as Akademien—a term that literally translates to “academies” but that also encompassed conversation and salon-style sociability. This context, situated in an intermediate space between the private and public spheres, allowed Martines to meet the social and musical luminaries of her age and share her musicianship with them. By meeting, conversing with, and performing for them in the context of her Akademien, Martines exerted influence on her musical environment.

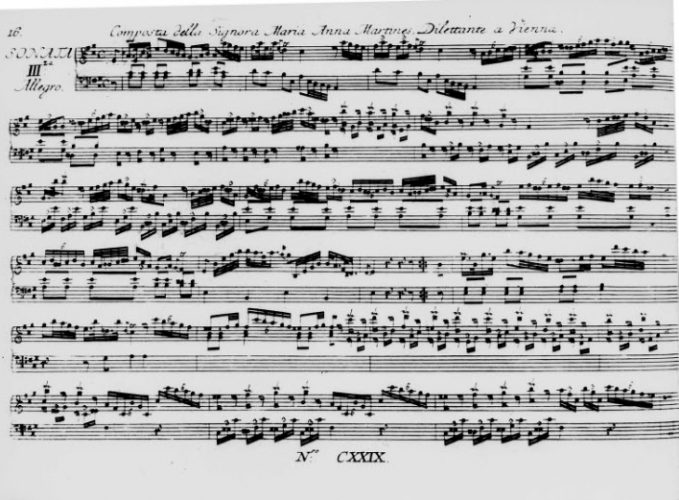

Early on, Martines published two keyboard sonatas. In 1762 and 1765, respectively, these pieces appeared in an anthology put out by the Nürnberg printer Johann Ulrich Haffner in a series titled Raccolta musicale contenente VI. sonate per il cembalo solo d’altretanti celebri compositori italiani messi nell’ordine alfabetico co’ loro nomi e titoli (“Musical anthology containing six sonatas [per volume] for solo keyboard by various celebrated Italian composers, placed in alphabetical order with their names and titles”). In reality, not all the composers in the anthology were Italian, but the styles of their keyboard pieces reflect the Italian taste, especially the brilliant yet technically accessible style of the Neapolitan galant. This tradition, indeed, was the one with which Martines aligned herself in recounting her musical influences in a letter to Padre Martini. Martines is the only woman composer represented in Haffner’s anthologies, and the only one without a professional title attached to her name. Instead, she is identified as “Signora Maria Anna Martines, Dilettante a Vienna.”

The term “dilettante” was one that Martines would apply to herself again later in the 1760s. A substantial two-volume manuscript of her Italian arias dated 1767 bears the title Scelta d’arie composte per suo diletto—“Choice Arias Composed for Her Own Delight.” This title represents Martines’ insistence that she be understood as an amateur who composed only for “delight” and not someone whose social situation required her to earn a living through music. Thus, although her status as a woman composer might have rendered her an object of public scrutiny, she seems to have described herself consciously as a “dilettante” as a means of deflecting some of the criticism that was sometimes leveled at women whose work appeared in public.

Drawing on her social connections and her careful cultivation of her public image, Martines successfully negotiated the pressures on women in 18th-century Europe to conform to expectations of modesty. Indeed, her fortunes rose considerably during her lifetime. Although her family was not of aristocratic lineage, her brothers ascended to knighthood in the 1770s, entitling Marianna to sign her name “von Martines.” After Metastasio’s death, she moved to a more fashionable neighborhood in Vienna and greeted guests in a musical salon on Saturday nights, hosting figures such as the Irish tenor Michael Kelly, the English writer Hester Thrale Piozzi, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Bold Choices, Fewer Connections

The risks of assuming a fully public persona as a composer would have been clear to Martines, and they are exemplified in a crisis in the career of Maria Rosa Coccia—one in which Martines was apparently involved. In 1774, five years before her own induction into the Accademia filarmonica, Coccia became the first woman to pass the qualifying examination of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia to earn the title of maestra di cappella in Rome, thereby gaining the right to work in churches in that city.

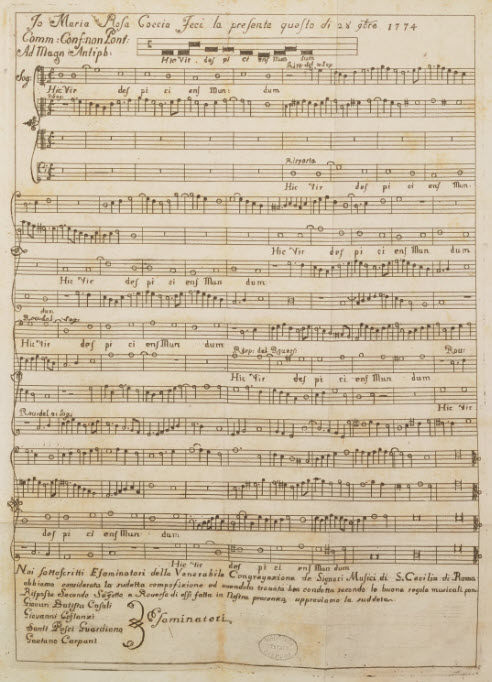

Coccia did not come from a musical family, so her father had arranged for her to study counterpoint under Sante Pesci, maestro di cappella of the Basilica Liberiana. The fugue Coccia created for her examination was later published in a pamphlet titled Esperimento estemporaneo fatto dalla Signora Maria Rosa Coccia romana. The publication opens with a single page of four-voice counterpoint—Coccia’s fugue on the antiphon “Hic vir despiciens mundum”—and concludes with a declaration of approval by the four examiners, one of whom was her teacher, Pesci. The remainder of the slim pamphlet contains epigrams and poems written in Coccia’s praise.

When Martines was inducted into the Accademia filarmonica, she had also been required to compose counterpoint; she sent Padre Martini two fugues that she would later incorporate into her Mass in C. However, her contrapuntal pieces were not the ones she published. Instead, in Martines’ few forays into music publication, she associated herself with the light, galant style, and with the genre of the keyboard sonata rather than learned, fugal composition. While Coccia was initially celebrated as a marvel—a woman who had achieved success as a composer and held the right to work as a maestra di cappella—her choice to publish her counterpoint was apparently considered a bolder step than those undertaken by Martines. Combined with the fact that she had fewer connections in the musical world, it left her exposed to criticism and attack.

As musicologist Marie Caruso explains, rumors soon began to circulate that Coccia had only succeeded in passing the examination at Santa Cecilia because she was a woman. These rumors were most likely spread by Francesco Capalti, who finally published his objections in 1781, pointing to what he considered damning evidence of Coccia’s faulty counterpoint. In fact, Caruso argues that Coccia’s published fugue as well as 10 others that were held back from publication followed new trends in counterpoint that Capalti simply did not accept. Capalti himself was still smarting from having failed the examination at Santa Cecilia, and it is possible he sought to undermine Coccia out of professional jealousy. After Coccia was admitted to the Accademia filarmonica in 1779, Capalti wrote to Padre Martini to complain about improprieties in modern counterpoint, and he included a copy of Coccia’s published fugue in support of the argument in his letter. Coccia’s reputation never recovered from these public humiliations. Despite having qualified to become a professional maestra di cappella, she never attained a professional position in church or court.

Even before Capalti had published his attack on Coccia’s counterpoint, another volume appeared in praise and defense of Coccia. The Elogio storico della signora Maria Rosa Coccia romana contains a biographical account, laudatory poems (some reproduced from the Esperimento estemporaneo), and letters written in Coccia’s support. The authors of these letters included some of the musical luminaries of the age, including Padre Martini and the castrato singer Farinelli, as well as several by Metastasio. In the first of these, Metastasio thanks Coccia for having sent her “three excellent pieces of her musical composition, which I saw, and respected.” Admitting, though, that he had been “unable to judge of their worth,” Metastasio explained, “I therefore instantly called a person extremely skillful in the art [of music], who, after carefully examining them in my presence, and with great pleasure, assured me, that they were written, not only in a correct, but masterly, manner. I rejoiced at this, and was flattered to find, that my dear country produced young ladies of such uncommon abilities.”

The musicologist Irving Godt has argued that “the person extremely skillful in the art [of music]” on whom Metastasio called to evaluate Coccia’s compositions was Marianna Martines. When Metastasio called on his anonymous expert to judge Coccia’s work, Godt observes, “Metastasio carefully hid his expert’s identity and (using the Italian word persona) sex.” This suggestion is entirely plausible, especially given Metastasio’s claim that he had “instantly” placed Coccia’s work before his expert’s eye; who better to turn to than the young musician with whom he shared an apartment?

Writing a letter he knew would become public, Metastasio shielded Martines from public involvement in this debate. Naming Martines openly would have undermined her carefully cultivated social standing even as it would have opened the door to public scrutiny and potential attack on her compositions. Moreover, Metastasio’s description of the event casts his anonymous expert in the role of a patron. Hiding the identity of his expert implied that she was of a higher social standing, from which perch she was capable of bestowing approval on Coccia’s compositions.

This episode, then, highlights the tensions surrounding women’s forays into composition. For Coccia, born into a professional class and lacking familial connections in music, a public career in music appeared to offer the most promise for success. For Martines, by contrast, public acclaim by an institution such as the Accademia filarmonica apparently required attenuation through anonymity in other respects. When Martines published, she presented compositions without pretense of serious learning, and when she performed, it was in the intermediate space of her musical Akademien, situated between the public and private spheres, rather than in full view of the public eye. The chance circumstances of being born into favorable circumstances, together with careful cultivation of her public image, shielded Martines from attack, while Coccia apparently suffered due to limited social connections and public exposure.

Rebecca Cypess is Associate Dean for Academic Affairs at the Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University. She is the author of the forthcoming book Women and Musical Salons in the Enlightenment (University of Chicago Press, 2022). A historical keyboardist, Cypess is the director of the Raritan Players, whose recordings to date explore performance practices and repertoire associated with 18th-century women