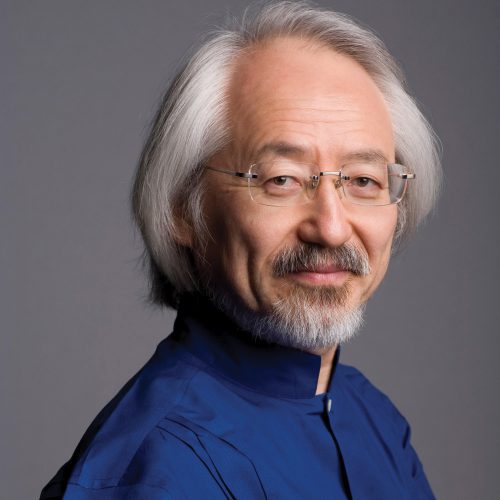

Bach Collegium Japan founder and Juilliard and Yale faculty member Masaaki Suzuki is exploring new (old) territory

By James L. Paulk

from the May 2018 issue of EMAg

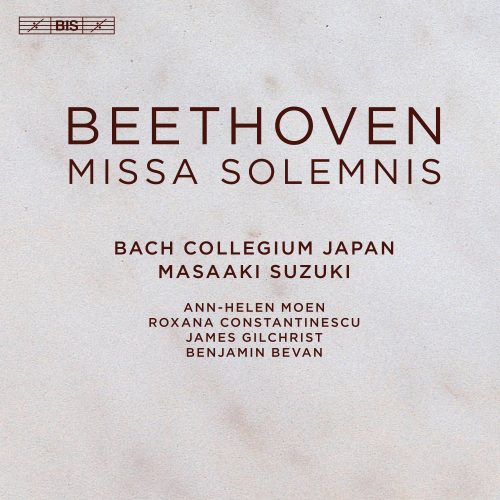

Ever since Masaaki Suzuki founded Bach Collegium Japan in 1990, the period-instrument ensemble and chorus have focused intensely on the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. Their rare performances of other composers have mostly involved Baroque figures, such as Buxtehude or Handel. In upcoming European concerts, however, BCJ will venture into the Classical and early Romantic periods, performing works by Haydn, Mozart, and Mendelssohn. A recording of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis was released in February, and the ensemble previously recorded the Mozart Requiem.

Suzuki, 64, sees this as a natural evolution. But it comes after decades of singular devotion to Bach and a deeply considered theological philosophy that has informed Suzuki’s approach to music from an early age.

Surely few Bach fans a generation ago could have foreseen that one of the most iconic and revered interpreters of his music would come from Japan. Bach was deeply religious, and his music reflects his Lutheran Christian beliefs. In the West, we experience it as part of our history and culture, and many of us grew up hearing and singing Bach in church services. And, while Christians comprise a tiny minority in Japan, that’s just what happened with Suzuki, whose parents were Protestants—and musicians.

Suzuki said his passion for Bach began at age 12, when he played the organ for services in the small church his family attended. “At that time, Karl Richter was really famous,” he said. “I bought a couple of his recordings—organ, harpsichord, B Minor Mass, and so on. And that made me very close to Bach’s music.

Suzuki said his passion for Bach began at age 12, when he played the organ for services in the small church his family attended. “At that time, Karl Richter was really famous,” he said. “I bought a couple of his recordings—organ, harpsichord, B Minor Mass, and so on. And that made me very close to Bach’s music.

“I had only a small harmonium in the church. I tried to play all this music, but soon I realized that I had the wrong instrument. Then a Belgian priest based in Osaka helped arrange access to some of the few pipe organs in Japan. There were not many at that time! Much later, I got to know other period instruments. I belong to the second or third generation of period instruments in Japan. The real pioneers built their own harpsichords.”

Suzuki soon found mentors. His first harpsichord teacher had studied with Gustav Leonhardt in Amsterdam. He continued his studies in Europe and taught there before returning to Japan.

Suzuki’s approach to Bach is thoroughly informed by his deep faith (he is a member of the Reformed Church). In the liner notes for the Collegium’s last Bach cantata recording, he wrote: “God left us the Bible. Into the hands of Bach He delivered the cantata. That is why it is our mission to keep performing them: we must pass on God’s message through these works and sing them to express the Glory of God.”

“Until recently, we have really concentrated on Bach’s music,” said Suzuki, speaking of the Collegium with typical understatement. In 2013, the BCJ finished recording Bach’s 191 church cantatas, a project that took 18 years and filled 55 discs. A highly regarded organist, Suzuki is well on the way to recording all of Bach’s organ music, though, he added, “I’m not sure I can complete it.” He finished recording Bach’s works for solo harpsichord in February. He is one of very few musicians ever to record Bach’s complete four-volume Clavier-Übung, which includes music for organ as well as harpsichord.

Regarding the ensemble’s transition to music past the Baroque, Suzuki focuses on links between works

Regarding the ensemble’s transition to music past the Baroque, Suzuki focuses on links between works

of different eras. “Now that we’ve completed all the cantatas and most of his instrumental music,” he said, “we are so much interested in following the line of the sacred music tradition, especially in the Masses. We’ve done the Bach B Minor Mass so many times, as well as the Mozart C Minor Mass, and now the Beethoven Missa Solemnis. These three compositions are interesting and closely connected. None of the three was written to be performed in a service.

“What form was the B Minor Mass written for? It was written at the very end of Bach’s life, using very much the musical elements from his youth. So, he was trying to complete his life! The C Minor Mass, which Mozart left uncompleted, was probably composed in part to persuade his father to accept his wedding to Constanze, and the soprano has wonderful solo parts in there.

“The Missa Solemnis was written at the end of Beethoven’s life, when he was having a lot of personal difficulties, and it was written together with the Ninth Symphony. It was such a different situation from the usual, and it’s interesting how he composed it. He was so serious: he made his own translation of the Latin text into German. And he has so much detail in the score—almost a Baroque composer! It is said that the Missa Solemnis is among the most difficult works to understand—why he composed it that way. But once you know Bach’s B Minor Mass and Mozart’s C Minor Mass, you realize that Beethoven has transformed the texts into music in the same way as Bach.”

Mozart’s C Minor Mass will be featured in two upcoming BCJ concerts: at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam on May 29 and at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées in Paris on May 30. Both concerts will also include Haydn’s Symphony No. 48, “Maria Theresia.”

On June 9, the ensemble will visit Leipzig’s historic Thomaskirche, where Bach was Kapellmeister, performing three Bach cantatas as part of the Leipzig Bachfest “Ring” of cantatas. “Thirty in one weekend: a really crazy plan,” said Suzuki, laughing. This will be followed by a performance of Mendelssohn’s Elijah at the Gewandhaus on June 12.

In Japan, where it is based in Kobe and Tokyo, the BJC has an annual series of five concert programs, along with a variety of special projects each year. Their next visit to the U.S. is still being planned, but Suzuki will conduct Tafelmusik’s performances of St. Matthew Passion in March 2019 in Toronto.

The Collegium has a core group of about 25 players and 20 singers. Suzuki describes them as “kind of a mixed group.” Most of the choir members are Japanese. The soloists, all of whom sing in the choir as well, might be Europeans. The core members of the orchestra are Japanese—the generation of his brother, Hidemi Suzuki, who plays cello continuo, and his schoolmates. “We’ve added wind and trumpet players from Europe, and now it depends on the repertoire. We have some guest players, of course. For the Missa Solemnis, we have 60-70 total [singers and players], and we’ll have 90 total for the Mendelssohn.”

Several family members are part of the Collegium, including Masato Suzuki, Masaaki’s son, the ensemble’s organist and harpsichordist. Asked how the players felt about these new ventures, Masato said: “Ten years ago, we would have felt otherwise, but now the group has matured, becoming more forward-facing, and it is a natural development for us to go into this repertoire.”

How differently does the group approach these more modern pieces in terms of historical performance practice?

“The string instruments and bows are totally different,” said Masato. “Our players are specialists in terms of historical instruments, so they do thorough research. And, of course, we have a much bigger choir. And inside the project it feels really different—more ‘excited.’ But then we come back to Bach and we feel very much at home.”

Masaaki Suzuki responded quite differently to the same question, insisting that the fundamental approach was really the same: “With [Missa Solemnis], the key is the relationship between the music and the text. I didn’t need any other attitude or approach, other than Bach.

We had been doing the cantatas, and there the texts and music are so connected. You see the same thing in the Beethoven. The choice of instruments, for example, is because of the text. In the passages about Christ on the cross and the Resurrection, the music is nothing but a description of the text. It has nothing to do with any of the Beethoven symphonies or any other music—no form of sonata or rondo. It simply describes the text.”

When asked about future forays beyond the Baroque, Suzuki responded: “I don’t know how far we should go with this. I hope we can go further with Mendelssohn, probably recording Elijah. And probably some Schumann, into the first half of the 19th Century.” Asked about Brahms, he said, “No, that would be too much for us, setting-wise.”

In addition to his work with the BCJ, Suzuki maintains a busy schedule as an organist and harpsichordist, guest conducting many of the world’s greatest orchestras, and teaching. My conversation with him took place in Paris, where he teaches at the Conservatoire de Paris.

He is a visiting professor through a joint project with the Yale School of Music and the Yale Institute of Sacred Music, where he serves as principal guest conductor of the Yale Schola Cantorum.

In recent years, Suzuki has collaborated with Juilliard Historical Performance, working with the Juilliard415 ensemble. “The problem is that Yale doesn’t have a period-instrument orchestra, and Juilliard doesn’t have a choir. So I came to Juilliard through Yale, and we have a joint project with both, but I continue to work with them separately as well.” Last year, Suzuki led the Juilliard ensemble on a 10-concert tour of New Zealand, and they will join the BCJ for the Mendelssohn performance in Leipzig.

When working with student ensembles, Suzuki typically spends at least a week preparing for a concert. These are intense projects. “We typically have two sessions a day for three or four days, then more advanced rehearsals, and finally the performances.”

The student performance in Paris a few days after our conversation was typical and telling. It took place in the German Protestant Christuskirche and was integrated into the church’s worship program.

The student performance in Paris a few days after our conversation was typical and telling. It took place in the German Protestant Christuskirche and was integrated into the church’s worship program.

In the program, Suzuki wrote: “If today we listen to Johann Sebastian Bach’s music in concert, it is important to remember that his cantatas were written for worship, with no idea of posterity. The German Protestant Church offers us the opportunity to make these masterpieces heard in their original setting. The choice of the cantata follows the liturgical calendar to stay closer to the writing context. First performed during the 10:30 worship service, then commented on in the preaching, it is repeated in the noon concert, with a program that includes a large organ piece played by a student organist.”

Although Suzuki has spoken of “carrying the message of the Bible to the audience,” he is the gentlest of messengers, self-effacing and quick to laugh. And he is utterly pragmatic. Asked if he saw his work as a mission, he said, “Actually, I am hoping it will be that, eventually. You know that to give a good performance, you have to be practical. Whatever aim we have, we must practice and work hard. But in the end, our work is to carry the message from the text to the audience.”

James L. Paulk is a freelance critic based in New York